Many of the traditions we associate with Easter can be traced back to celebrations that honored Ostara, or Eastre (Old English), an ancient pagan Germanic goddess of spring. Associated with the radiant dawn and the reawakening of nature, she represented the renewal of life, joys, and blessings. Such imagery could easily be incorporated into the Christian festival of Christ’s resurrection and the dawning of eternal light and promise.

There were pagan customs that the Christian church reformulated to fit into its rituals, and others that it tolerated. Among the latter were the so-called Easter games that included the symbolic egg. It was viewed as a mysterious capsule that hid a developing being only to be brought forth when the shell broke. Eggs were decorated and offered up in the great spring festivals of yore. The hare also was part of pagan ritual: As one of the most fecund animals known, it became a symbol of fertility.

Georg Franck von Frankenau first wrote about the Alsatian tradition of a Hare bringing Easter eggs in his De ovis paschalibus or About Easter Eggs in 1682, but it was the Pennsylvania Dutch who brought the tradition of the Easter Hare or Oschter Haws to Pennsylvania. Children believed that if they were good, an Easter hare would lay eggs in the grass for them.

o osterhaas, o osterhaas, O Easter hare, O Easter hare,

leg dyni eier bald ins gras! quickly lay your eggs in the grass!1

Little boys made nests out of their hats, and little girls from their bonnets, which they then put outside in the grass on Easter Eve for the Oschter Haws to lay his eggs for them. The eggs they found the next day may have been a dark rusty brown from the onion skins their mothers had used to dye them the preceding Maundy Thursday, but no matter. A child’s imagination is a place where colors are mixed the hue of the heart.

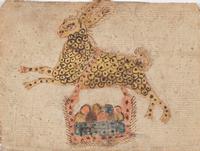

It was Johann Conrad Gilbert (1734-1812), a Pennsylvania Dutch school teacher and Fraktur artist, who first made a drawing of the Easter hare, probably as a Belohnung or reward for one of his school children. Two examples are known to exist: one at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia, and the other at Winterthur2. Gilbert also produced many Taufscheins, bookmarkers, and miscellaneous drawings. The Borneman Pennsylvania German Collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia has one of his birth and baptismal certificates made for a son of Johannes and Eva Fleischer, born in Reading, Pa. on June 11, 1780 (FLP 1051).

1 Translation by Del-Louise Moyer

2 N.B. Blog image courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Drawing of Easter rabbit with eggs, by Johann Conrad Gilbert, 1800-1810, Berks County, PA, museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle, 2011.10

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.