A History Minute: Octavius V. Catto - Philadelphia's Forgotten Freedom Fighter

By AdministratorOn Sept. 26, 2017, the fence will come down and a new statue will be unveiled: the first new City Hall statue since 1923 and the first of an African American on any city-owned public property. It’s a lot of fuss over a man most Philadelphians have never heard of, and it’s about time.

When we speak of the Civil Rights Movement, we think of the 1950s and 1960s with leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Cecil B. Moore, but the movement really began in the 18th century and reached a peak in the years after the Civil War. Free blacks all over the country grasped at a new equality even as many whites fought to defend their hegemony.

Octavius Catto led that fight in Philadelphia.

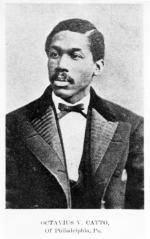

Octavius Catto was born in South Carolina in 1839 to Sarah Cain and William Catto, a former slave who had managed to buy his freedom and become a Presbyterian minister. Catto brought his family north and settled in Philadelphia where he sent his son to the Institute for Colored Youth, which later became Cheney University. Octavius Catto graduated in 1858 as valedictorian and continued his study of classical languages in Washington before returning to the Institute as Vice Principal and teacher of Mathematics and English. Catto had become an intellectual, a powerful public speaker, and a gifted athlete. He devoted all of these abilities to the fight for equal rights.

Catto approached civil rights from several directions, speaking out and standing up for his rights but also demonstrating the value of African Americans to society. He raised one of the first volunteer companies of troops in response to the invasion of Pennsylvania during the Civil War and served as a Major in the Pennsylvania National Guard.

Catto led the fight to desegregate Philadelphia’s streetcars and took the battle to Harrisburg, which passed the legislation in March 1867, 90 years before Rosa Parks. He established the Banneker Institute, a black literary society, and became the first African American inducted into the Franklin Institute. And 80 years before Jackie Robinson, Catto fought to integrate baseball.

Before the Civil War, baseball was played mainly in the Northeast and Midwest, but it spread quickly as soldiers and prisoners of war played the game to pass time in camp. The end of the war saw the proliferation of baseball throughout the country and it became a popular spectator sport. Black players, restricted from joining white teams, began to form their own.

Catto, a gifted shortstop, gathered former teammates from ICY and friends from the Banneker Institute and formed the Pythian Baseball Club in 1866. They lost their first game, but finished the season 9-1 and were acclaimed as the best team in the city. The Pythian Club wanted to compete against white teams and applied to join the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Amateur Association of Baseball Players but was voted down. Philadelphia fans were not to be denied though and in 1869, the Pythians played against the white Olympics. The Pythians lost, but were deemed good enough to play against several white teams in coming years.

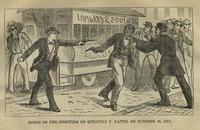

The passage of the 15th amendment in 1870 prevented restrictions on voting rights and meant that black men would be able to vote in the 1871 elections. On election day, groups of white men, many fearful of losing their jobs to blacks who might work for lower pay, gathered to intimidate black voters. After voting himself, Catto sent the teachers and students at ICY home to safety and notified the Fifth Brigade to prepare to be called in to maintain order. He then walked to his home at 814 South Street to get his uniform. Just before reaching his door, he was shot twice in front of many witnesses and died almost immediately. He was 32.

Catto’s funeral service was held in the City Armory at Broad and Race Streets. Over 5000 mourners formed the funeral procession and included many from other states including Delaware, New York, and Mississippi. Speakers sang his praises in churches and halls all over the country. For years afterward, schools were named after him, but his murderer was acquitted and many of the rights he was fighting for did not come to pass until well into the next century.

Learn more by...

Listening to our podcast:

Reading about the life of Octavius V. Catto from these catalog selections:

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.