William Penn was a dreamer. Like many attracted to the New World, he was a member of a persecuted religious minority—the Quakers. But unlike the Puritans and Catholics who founded religious states of their own, Penn envisioned a utopia where all would live in peace and prosperity while worshiping God as they chose. He believed that a mix of religious beliefs and backgrounds would create a more stable and prosperous society. Penn wrote pamphlets promoting his new colony that were translated into Dutch and German and made several voyages to Europe to recruit settlers.

“Certainly the civil affairs of all governments in the world may be peaceably transacted under the different liveries or trims of religion, where civil rights are inviolably observed." (from England’s Present Interest Considered” by William Penn, 1675)

Penn’s plan worked and by 1776, Philadelphia was the largest city in America with a population of 32,000. The immigrants included servants, laborers, farmers, craftsmen, slaves, free blacks, and wealthy landowners. They came from the British Isles, Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and other American colonies. They were Quakers, Presbyterians, Lutherans, German Reformed, Baptists, Anglicans, Methodists, Mennonites, Amish, Catholics, and Jews.

By the end of the century, the flow of immigrants from Germany and England slowed dramatically and the majority of Philadelphia’s immigrants were Irish Catholics thrown out of work by the mechanization of textile mills, and later fleeing the potato famine. In just 20 years (1830-1850), the Catholic population increased from 35,000 to 170.000 and 70 new Catholic churches were built.

Workers feared losing their jobs to immigrants willing to work for lower pay and Protestants feared loss of political power. Both groups used religious differences to gain support for their cause. Protestant clergymen founded the American Protestant Association in 1842 to alert the public to the dangers of "popery," and in 1843 newspaper editor Lewis Levin helped found the American Republican Association (later renamed the Native American Party).

Matters came to a head in the 1840s. In 1843, Irish Catholic Bishop Francis Kenrick had learned that all school children began each day with a reading from the King James Bible (a Protestant bible) and he had asked the Board of Controllers, who managed the schools, to allow Catholic children to use the Douai Bible. The board considered this a reasonable request and granted it. But rumors began to spread that the Catholics were attacking the Protestant bible and trying to ban it from the schools or trying to take over the schools entirely.

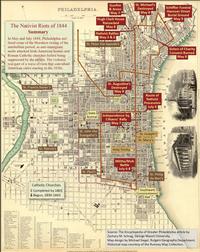

Nativist leaders saw this as an opportunity to further their cause and the American Republican Association held a rally on May 3, 1844 in Kensington, the industrial neighborhood just north of the Philadelphia city limits where many Irish immigrants—Catholic and Protestant—lived. Residents brought the rally to an end, but thousands of nativists returned to Kensington on May 6 where fighting erupted again resulting in the death of several nativists. Nativists retaliated over the next two days by burning homes, a Catholic seminary, and two churches: St. Michael’s (2nd and Master St.) and St. Augustine’s (4th and Vine St.). It took the combined efforts of the U.S. Army and Navy, militias from other cities, city police, and bands of residents to finally end the chaos on May 10. Many residents lost their homes and were forced to live in tents in Fairmount Park for weeks until they found new ones. A grand jury blamed the Catholics for the riot.

The city remained calm for several weeks until early July, when the priest of St. Philip Neri, a Catholic church near 3rd and Queen St. in Southwark, learned of a planned nativist rally in the neighborhood and organized a group of parishioners to defend the church. He also alerted the state militia and borrowed 25 muskets from the Frankford Arsenal. On July 5, observant nativist neighbors saw the muskets being delivered to the church and spread the word. By noon on July 6, thousands had gathered in the streets around the church. The militia dispersed them, but they returned on July 7 with several cannons taken from the docks three blocks away. The fighting went on for days, resulting in 20 deaths and many injured. It took 4,000 military and volunteer troops to restore peace. Once again, a grand jury blamed the Catholics for the riot.

While many towns saw nativist riots during this period, Philadelphia’s were by far the longest and most damaging with many unforeseen consequences. The riots and fear of Catholics became an issue in the federal elections in the fall of 1842, as nativists won several congressional seats. The riots were one of the rationales for the Consolidation of 1854, which expanded the city boundaries to its present limits.

Bishop Kenrick abandoned his efforts in the public schools and founded the first Catholic school system in the United States, right here in Philadelphia.

Learn more about the riots with local historian Kenneth Milano in the following 6-part video series from the Northeast Times:

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.