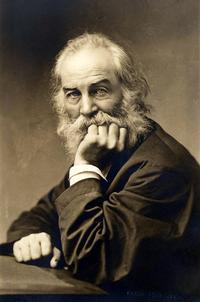

At the end of the film Dead Poets Society, the students who loved their professor, Mr. Keating (played by Robin Williams), stand up on their desks and proclaim, "O Captain, My Captain" as a sign of allegiance and respect. Back in the early 90s, as the credits rolled, my best friend and I snuck away from the group of teens watching the movie in a church basement, found an empty classroom, and stood on desks with our arms in the air, whisper-screaming the same, "O Captain! My Captain!" We were jubilant and moved and wanted to yell to the universe the truths in our mushy teenaged souls. I’m not sure if our "captain" was Mr. Keating, Robin Williams, the film, or poetry. Maybe it was a little of each, but it drove me to start reading our revered American poet, Walt Whitman, from whose poem the honorific is derived (it’s about the death of Abraham Lincoln, so the story goes). Whitman’s work has an ecstatic quality that still makes readers want to stand on desks (or maybe rooftops) and revel in the natural and built worlds.

Whitman was a rule and boundary breaker – both in his life and in his poetry. While he started out writing in the standard tradition of the day, he soon let go of verse in rhymed and metered stanzas, or in structured forms at all. To give you a sense of this, take a look at these few lines from Whitman’s contemporary, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was about 10 years older but generally writing during the same time as Walt (and also had a whopping white beard). This is from The Evening Star,published in 1846:

Lo! in the painted oriel of the West,

Whose panes the sunken sun incarnadines,

Like a fair lady at her casement, shines

The evening star, the star of love and rest!

Reminds you of why you hate poetry because your 11th grade English teacher made you memorize it but never talked with the class about its relationship to your 20th/21st century life? Yeah, me too. And now take a look at these lines from Whitman’s "Are you the new person drawn toward me?":

Are you the new person drawn toward me?

To begin with, take warning, I am surely far different from what you suppose;

Do you suppose you will find in me your ideal?

Do you think it so easy to have me become your lover?

Plain language, rangy lines, nothing sing-song about it. This was published in 1860, right before the nation was about to split apart and pitch forward into its bloodiest war. Whitman wanted to be—and was convinced he was—the people’s poet. When he first tried to publish his master work, Leaves of Grass in 1855, even the avant-garde publisher in New York wasn’t prepared to support what Whitman was after, so he self-published and took it on himself to get it into the world.

He also took a hard look at the effects of war and capitalism on American life and strove to communicate about these issues with colloquial language that wouldn’t have been seen in other poetry of the day. On the other hand, the pastoral life and colloquialism he ascribed to was one where racism and oppression thrived. In this essay by some-time Philly poet CAConrad, the veil is lifted and we see that Whitman's prose was not all encompassing and was, in fact, narrow, to say the least. How should we contend with that in 2018? Is it possible to separate the art from the artist? What do you think Whitman would make of America today?

May 31, 2018 marks the 199th anniversary of the poet’s birth. Let’s dig back into our teen minds and dredge up some goopy passion for Whitman’s poetry. Let’s be passionate with a critical eye. Perhaps there’s instruction to be found there.

If you’re interested in reading more about Whitman’s life and work, some of the facts from this post were picked up in reading Walt Whitman’s America: a Cultural Biography by David S. Reynolds. Check out the other texts in our catalog about and by Whitman available at the Free Library.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.