Never having been much of a history buff, and possessing a wholly striking inability to memorize dates, my cultivation of Philadelphia history has been mostly through passive absorption. I have lived in Philadelphia long enough to have passable knowledge of the "founding fathers," the Liberty Bell, Eastern State Penitentiary, and the 1985 MOVE bombing. Part of the problem with being a person who mostly takes in history through osmosis is that if history is not visibly present, it doesn’t get absorbed. Reading There There, I wanted to learn more about the history that is not readily displayed in monuments, museums, or ubiquitous historical reenactors. There is not even that much history in this blog post, but what is here took some digging.

Philadelphia is Lenapehoking, or the unceded land of the Lenni-Lenape peoples. While this is historical information, it is also the present and the future, meaning there are still Lenni-Lenape people and there will continue to be. "Lenape" is not the name of a single tribe; it originally meant three separate clans of the Unami, the Munsee, and the Unalactgio, otherwise known as the Nanticoke (these territory-oriented identities were additionally comprised of matrilineal tribal identities). All of this is to say that there is not one singular Lenni-Lenape identity, just as there is no singular Native American identity. You can visit the headquarters of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation virtually or in-person in Bridgeton, New Jersey, to learn more about the local and regional history of the Nanticoke. However, because of historic displacement and forced migration, there are significant populations of Lenni-Lenape, Delaware (a name given to the Lenape by settler-colonists), and Nanticoke peoples based in Oklahoma and Ontario, Canada, outside of their homeland.

I had known that the Quakers of Pennsylvania had their own narrative about peaceable cohabitation and respect for the Lenape people. Of course, this makes it seem that there was no one living in Pennsylvania before them. To quote Tommy Orange: "But then when you hear them tell it, they make history seem like one big heroic adventure across an empty forest" (There There, p. 51). This is a colonial narrative that erases the evidence that human beings have lived in what we now call Pennsylvania for at least 16,000 years. Historian Jean R. Soderlund notes, "Like other founding myths that ignored the history of Native Americans prior to European colonization, the Pennsylvania legend wiped away the Lenape’s own history prior to contact with Europeans as well as the sixty-five years of exchange, conflict, accommodation, and alliance between the Natives and the Dutch, Swedes, Finns, and English" (Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn, p. 4).

William Penn opined about his peaceable dealings with the Lenape people. He was allegedly guided by the Quaker principles of peace, love, respect, understanding, and religious freedom and sought to give Lenni-Lenape people fair land deals. When he received his charter for Pennsylvania in 1681, he actively recruited Europeans to come join his colony, which contributed to the displacement and dispossession of Lenape peoples from Lenapehoking. Additionally, settlers brought diseases such as smallpox, measles, and others that decimated Native populations.

To my knowledge, there are two public monuments to Native Americans in Philadelphia that do not depict Lenni-Lenape figures, but token stereotyped images of Native Americans (three if you count the manhole covers of East Passyunk). There is the "Tedyuscung Statue" in Wissahickon Valley Park, wearing a Western Plains war bonnet, with no indication that this sculpture bears a resemblance to the actual Lenape people or Tedyuscung the individual. Tedyuscung, also written as Teedyuscung spoke out against the land grabs and attempted to negotiate a permanent land claim for the Lenape peoples. He argued, "This very Ground that is under me (striking it with his foot) was my Land and Inheritance, and is taken from me by Fraud." Needless to say that particular style of headdresses is not traditionally worn by the Lenape peoples and is falsely attributed to all First Nation and Native Peoples of the Americas by a media stereotype. A similar statue that does not seem to have a connection to local history but to the colonial idea of Native peoples resides in Fairmount Park.

Two other monuments pay homage to Tamanend, the head Lenape sachem who made the 1682 "treaty" with William Penn. According to the terms of this treaty, it was to be an agreement of friendship and shared usage. Penn and his children came to interpret it more as a land deal. This, along with other dubious land deals that were forged or granted by third parties, including the Iroquois Confederacy, further displaced the Lenape peoples. These "treaties" and the precarious position of the Lenni-Lenape (often caught between the French, British, Quakers, Swedes, Dutch, Iroquois, and the internal pressure from receiving Native American tribes that had been displaced from other regions) prevented outright war, but did not prevent incremental violence, uneasy exchanges, mounting pressure, and displacement. The piecemeal violence allowed Penn to maintain this narrative of peaceable coexistence, and Chief Tamanend’s figure has been used to countersign this narrative. This is indicative of the public story that Philadelphia is telling and why revised narratives often and importantly put this "time of peace" in scare quotes.

One of the statues of Tamanend was installed at Front and Market Streets in 1995. The other, installed across from Penn Treaty Park and drawing on images of the wampum belt, is by Bob Haozous, a Chiricahua Apache artist based in Santa Fe. Many have argued that the park, which has a statue of William Penn and a placard that acknowledges Penn’s treaty with “the Indians,” ought to have a statue of Tamanend and that the treaty and park ought to be called Shackamaxon, the historical and original name of this place and where the Unami clan would meet prior to Penn’s arrival. Bob Haozous’s sculpture does not give us the stereotyped image of the bare-chested male figure wearing a full headdress, but something more modern, and in that a reminder that Native peoples are not historical figures of the imagination but living peoples with living cultures, traditions, practices, and representations. Having living Native artists create these public works invests the power of representation back to the represented.

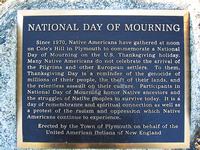

This call for self-representation echoes contemporary projects occurring throughout the Americas that seek to have a more accurate and honest reckoning with history and original inhabitants. These include having more accurate commemorative signage such as the National Day of Mourning plaque in Plymouth. Other projects include renaming public places with the names given by the original inhabitants, such as the renaming of Lake Bde Maka Ska in Minneapolis (pronounced beh-DAY mah-KAH skah), which is a Lakota name that means White Earth Lake. The lake had previously been named after a secretary of state who was a major champion of slavery. In Philadelphia, there are several places that retain their Lenni-Lenape names, such as Aramingo, Kingsessing, Manayunk, Susquehannah, and Wissahickon.

A practice that honestly commemorates regional history and acknowledges Indigenous peoples’ ongoing relationship with a place is having a land acknowledgment at events and gatherings. This is where you publically and formally acknowledge the traditional stewards and inhabitants of the land. It is a statement of respect for the living members of these Indigenous tribes and formal recognition of the historical and ongoing violence and injustice that Indigenous and Native American individuals face. Land acknowledgments, like the one shared at One Book events, are just a small symbol of a commitment to decolonization work, and must inherently go hand in hand with continual learning and building relationships.

My knowledge of the history of this place is incomplete. Ultimately this dive I took felt partially unsatisfactory, in that what I gained was the view from nowhere. What eluded me was a robust insight into the lived historical experience and the historical present. I look forward to the One Book, One Philadelphia events this January to March that center on Indigenous and Native perspectives and local histories that will allow me to expand my grasp on the ongoing histories and evolution of the place where I now live.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.