If you’re unfamiliar with poetry, or it’s just been a while since you really sat down and read a poem, we can walk through one together!

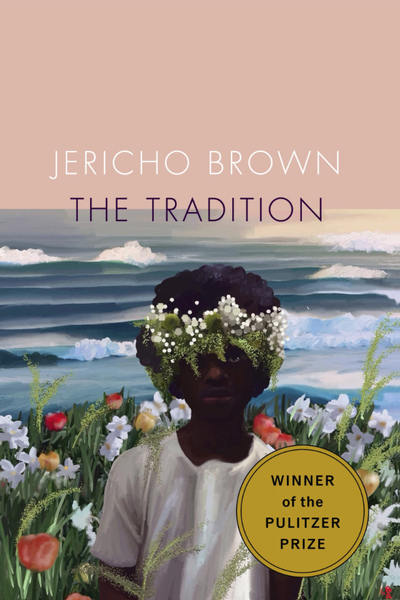

Here’s a look at some of the tools used by Jericho Brown in his collection The Tradition, this year's One Book, One Philadelphia selection.

Let’s start with Brown’s poem, "As a Human Being":

There is the happiness you have

And the happiness you deserve.

They sit apart from each other

The way you and your mother

Sat on opposite ends of the sofa

After an ambulance came to take

Your father away. Some good

Doctor will stitch him up, and

Soon an aunt will arrive to drive

Your mother to the hospital

Where she will settle next to him

Forever, as promised. She holds

The arm of her seat as if she could

Fall, as if it is the only sturdy thing,

And it is, since you’ve done what

You always wanted, you fought

Your father and won, marred him.

He’ll have a scar he can see all

Because of you. And your mother,

The only woman you ever cried for,

Must tend to it as a bride tends

To her vows, forsaking all others

No matter how sore the injury.

No matter how sore the injury

Has left you, you sit understanding

Yourself as a human being finally

Free now that nobody’s got to love you.

It comes with the territory of poetry that we will probably have to read a poem more than once to get a good feel of what it’s trying to tell us. A good way to start out is by reading it once, then reading it a second time through, out loud, just for the sound of the language. Reading a poem out loud can help us hear the music in a poem, created through things like rhyme and rhythm.

Rhyme is when two or more words with similar-sounding syllables echo each other. This often happens in an end rhyme with words at the end of a line, such as in these two lines from "As a Human Being":

They sit apart from each other

The way you and your mother

This rhyme scheme is a classic example of rhyming lines, but later in the same poem we can see an example of an internal rhyme, where the rhyming words are not at the end of a line, but inside it:

And it is, since you’ve done

You always wanted, you fought

Your father and won, marred him.

We might miss internal rhymes until we read them out loud—they’re sneaky that way! Now let’s talk about rhythm. Rhythm is best described as the beat or pace of a poem, much like the lyrics in a song. When reading this poem out loud, do you find the words sound different than they did in your head during your initial reading? Do the rhymes help you find a rhythm where you first didn’t see it?

Now that we’ve read the poem a couple of times and gotten the feel of it, let’s read it a third time to start to dive in to what the poem might be telling us. There are a few good questions to help us get to the meat of a poem, questions that can make the reading a little easier. Let’s start with a couple:

- Who is the speaker? What do we know about them?

- Who is the speaker talking to? How does that change how we read the poem?

- What’s happening in the first line?

A common word used when talking about a poem is "speaker," but what does that mean exactly? When we use the word speaker, we are talking about the voice the poem is "coming from," the "voice" reading the poem. It is important to remember that the speaker is not necessarily the poet, and it can help to think of the speaker as a character within the poem. So who is the speaker in this poem? Let’s look at the first two lines:

There is the happiness you have

And the happiness you deserve.

We can see in the first line there is both a speaker and a subject. The subject is who the poem is addressed to, the "You" of the poem. (Now, things might get a little confusing but bear with me.) Who is You? Does it mean you, the reader? The one reading this blog post right now? Or is it a different You entirely? What kind of relationship do You and the speaker have? Are they strangers? Do they know each other? Is it a friendly or antagonistic relationship?

We can ask ourselves, "Who do I think the speaker is? Who is You? Why might the speaker be addressing this poem to You? How do I relate to the You in these first two lines?"

What did you come up with?

So we’ve looked at the first couple lines a little bit, let’s dive in some more, and let’s ask a lot more questions.

There is the happiness you have

And the happiness you deserve.

They sit apart from each other

The way you and your mother

Sat on opposite ends of the sofa

One thing that helps when reading a poem is to single out individual words. Let’s look at "have" and "deserve." What is the difference between these words? We know that the speaker is talking about two kinds of "happiness". Does the speaker think "You" deserves more happiness than they have? Or less? Is this a sympathetic sentiment? Or is it aggressive?

So we’ve got the scene, what’s literally happening: You and You’s Mother are sitting on opposite ends of a sofa.

They sit apart from each other

But who is "they"? They is referring back to "the happiness you have", and "the happiness you deserve". What does it mean that "they" sit that way? Now, this is where poetry can get tricky; it can be hard to visualize two kinds of happiness sitting on a couch together. This image is the personification of the two types of happiness, sitting on the couch, just as You and You’s mother.

With those questions in mind, let’s move a little further down the poem.

They sit apart from each other

The way you and your mother

Sat on opposite ends of the sofa

After an ambulance came to take

Your father away. Some good

Doctor will stitch him up, and

Soon an aunt will arrive to drive

Your mother to the hospital

Where she will settle next to him

Forever, as promised. She holds

The arm of her seat as if she could

Fall, as if it is the only sturdy thing,

And it is, since you’ve done what

You always wanted, you fought

Your father and won, marred him.

What do we know so far? What has happened in the poem? Let’s make some quick observations of what the poem has told us objectively:

- "You" and the Mother are sitting on the couch

- The Father is in an ambulance on the way to the hospital

- The Father will be fine after getting stitches

- The Mother will soon go sit with him "forever"

- "You" has always wanted to fight the Father

- "You" has won

- "You" has marred him

What do we know about the relationships of this family, now that we’ve laid these things out? What has the speaker told us about this family dynamic? What can we assume now that we know the "facts" of the poem? What might have happened within the family dynamic before this moment?

You has "always" wanted to fight the Father and now won, perhaps for the first time, and it has ended with a trip to the hospital. The Mother and You sit on opposite ends of the couch, and the Mother will soon leave You to be with the Father, as it does not seem like You will join her there. What can we say about the relationship between this Mother and child? Let’s compare these lines:

…she will settle next to him

Forever, as promised

…you’ve done what

You always wanted, you fought

your father…

What do the words "forever" and "always" do? What do they say about what sides each member of the family is on?

If you read the poem again, right now, does it feel different this time around?

Now let’s move to the end.

…since you’ve done what

You always wanted, you fought

Your father and won, marred him.

He’ll have a scar he can see all

Because of you. And your mother,

The only woman you ever cried for,

Must tend to it as a bride tends

To her vows, forsaking all others

No matter how sore the injury.

No matter how sore the injury

Has left you, you sit understanding

Yourself as a human being finally

Free now that nobody’s got to love you.

In this last piece is an example of simile (pronounced sim-uh-lee): a figure of speech that refers to one thing by describing how it is similar to another; a comparison that swaps an idea for an image. If you are unfamiliar with the word simile, it is incredibly similar to the word metaphor. Let’s just look at a quick example, one metaphor and two similes:

The girl’s heart was shattered glass (metaphor)

The girl’s heart was like shattered glass (similie) or

The girl’s heart was as shattered as glass (also similie)

While these might seem identical, the words "like" and "as" play big roles. A good way to think of it is like this:

Metaphor: idea is image

Simile: idea is like image

Now, back to the poem at hand---

...And your mother...

Must tend to it as a bride tends

To her vows

The simile used here is the Mother tending to the Father’s scar "as a bride tends to her vows." The idea is the vow, promise, or obligation of a marriage; the image used is tending to a scar. What extra meaning in the story do we get from this simile, the relationship of a marriage vow and the Mother tending to the Father’s scar?

So we’ve come to the end of the poem. Let's read the last line out loud.

No matter how sore the injury

Has left you, you sit understanding

Yourself as a human being finally

Free now that nobody’s got to love you.

What is it telling us? What do you think? What does it make you feel? In what contexts do you normally think of the word "Free", and how does that shift or change after reading the story in this poem? How does the word "Free", at the end of the poem, relate back to the words "have" and "deserve" at the beginning of the poem? Does the speaker have the happiness they deserve at the end of the poem?

These are just some of the tools used in The Tradition, and in poetry more generally, that can help us as readers to connect to what the poet is trying to say. But even still, each reader will have a different reading of, and response to, the poem. In the end, there is no single right way to read a poem, because no poem has one single meaning. It’s open to interpretation, which is why it can be so interesting to discuss poetry with others, to hear the different meanings that we each find based on our own experiences. It might just take a few readings—but it’s worth it.

Join one of the many online book discussions around The Tradition this One Book season to hear how Jericho Brown’s poems make others feel and what they bring up for each individual.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.