Written by Lewis Shaw, who conducted extensive research in the Art Department as part of a Friends Select School Senior Internship Project.

During the extended fever dream which we all refer to as COVID quarantine, I picked up a love of artist biographies—I’d be reading one at any given moment in between high school Zoom classes and midday naps. From Egon Schiele to David Wojnarowicz to Francis Bacon, works of art and the artists behind them were always on my mind. By last summer, I had exhausted my personal backlog, and so I picked up a book simply titled Surrealist Art by Sarane Alexandrian. It was a comprehensive overview of the visual side of the surrealist movement, something that I knew I’d want to be familiar with before I left for college.

I read the book in a day or two between time spent in Rittenhouse and Washington Square, which had become my go-to relaxation spots during the pandemic. As I flipped through the pages, reading about artists like Brauner, Ernst, De Chirico, and many others, I noticed that there was a severe lack of female representation among the more known artists of the movement. Surrealism was, for the most part, a "boys’ club," exemplified by Max Ernst’s 1922 painting A Rendezvous of Friends. the piece is a portrait of surrealism, with its most important participants displayed together in a dreamlike landscape. Of the 17 figures, one of them is a woman, Gala Eluard, former wife of Paul Eluard.

Naturally, I wasn’t all that surprised—the world of art has always been dominated by male names and male faces. I was still somewhat flabbergasted by surrealism’s male exclusivity, since the movement was a rejection of societal standards in the name of the liberation of the mind. How could a movement advocate such self-determined freedom while remaining so sexist, so objectifying? My mind was brimming with curiosity, but as weeks blurred together in the fog of quarantine, it began to slip away from me, and I eventually turned to other books and subjects as my senior school year began.

My high school requires seniors to take on an internship for their final project before graduation, and I had the privilege of working with Alina Josan, a Librarian in the Art department at Parkway Central Library. When she asked me what I wanted to research, my mind immediately went back to surrealism, and so I began my project with "The use and representation of the female form in surrealist art."

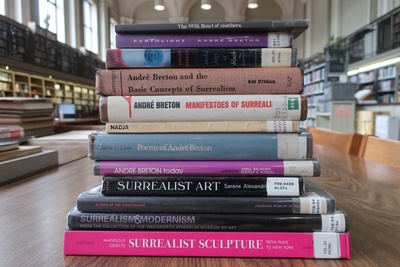

As I began my research, Alina would routinely ask me who I was reading about, and five minutes later, would walk back over to my table with a massive stack of books in her arms. I decided to do my research through the lens of specific artists, and the resources at the Free Library greatly aided me. I read books written by and about Andre Breton, Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, Remedios Varo, and Hans Bellmer. Keeping an eye out for anything that mentioned or depicted women, I quickly became familiar with the concept of the Femme Enfant, or, in english, "woman child". Coined by Andre Breton, the founder of surrealism, the Femme Enfant is one of the most common methods in which women were represented by male artists in their work. The idea of the Enfant reduces women to a plaything for the male artists of the movement, stripping women of their agency, and arresting them to the role of the infantilized and beautiful muse.

While most of the male artists in the Surrealist group treated women the same way, both in their art and in their relationships, one stuck out from the rest. Hans Bellmer was a German-born artist, who created doll sculptures in the early 1930s. Bellmer’s dolls are in many ways horrendous but also a form of underground protest against the Nazi idea of the idyllic youth, as well as general public perception of the "ideal" body. When comparing the faces of the dolls with the artist’s, the resemblance is unmistakable. Bellmer subverts gender norms and societal boundaries by blurring the line between desire and complete disdain, beauty and the grotesque, youth and decay, and traditional gender power dynamics.

After I established an understanding of how men viewed women in surrealism, I moved onto researching how women chose to represent themselves in the movement, reading about Carrington and Varo.

Stay tuned for part two of this blog post soon and check out the following catalog list for more resources on Surrealism and gender.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.