As part of his bold New Deal aimed at national reform and recovery in the wake of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the Work Projects Administration (WPA). The federally funded program focused on putting people back to work and employed some 8.5 million Americans to construct 650,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 125,000 buildings, and 800 miles of airport runways. Beyond infrastructure, the WPA reached out to the arts with projects designed for writers, artists, and musicians—some of the first to lose their jobs in the economic downturn.

The Fleisher Collection would take hold of the biggest and most important Federal Music Project in the nation, and this is how it happened.

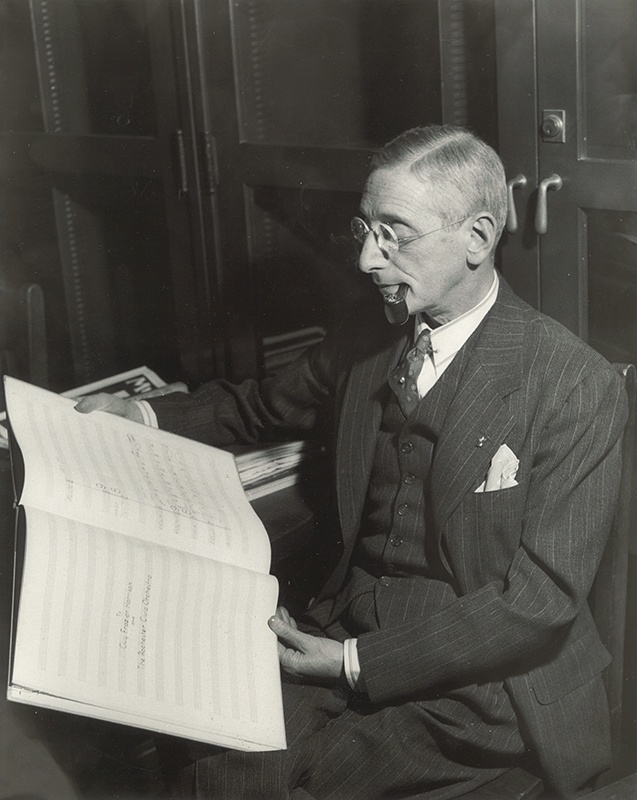

By 1933, Philadelphia worsted wool magnate and music philanthropist Edwin Adler Fleisher (1877-1959) had already established the first training orchestra in the nation (founded in 1909) and assembled the largest collection of orchestral performance sets in the world. Each set comprised a score for the conductor and an instrumental part for each musician sitting in the orchestra, with everything necessary to perform the specific work. After spending as much as $20,000 annually to create his collection, he donated it to the Free Library in 1929 and privately published—at his own expense—700 numbered copies of a descriptive catalogue of the collection’s holdings. Prepared with the assistance of noted musicologist Karl Geiriger, it "remains an invaluable reference tool for all librarians, critics, students, radio stations, and professional musicians concerned with orchestral repertory."1

For each entry, the catalogue lists:

- Date and place of birth and death of the composer

- The title of the work in its original language and the translation into English

- The publisher

- The instrumentation, showing not only the different instruments for which the work is scored, but also the number of each woodwind and brass instrument required for the performance

- The approximate length of time, in minutes, required for performance

- The date of composition; the place and date of the first performance; the orchestra; the conductor; and in the concertos, the soloist.2

A simple survey of the 1933 catalogue’s contents reveals what Fleisher already knew—the collection "was lacking in the works of New World composers."3 While the collection held older previously published works by well-established American composers such as John Powell (1882-1963), George Chadwick (1854-1931), Arthur Foote (1853-1937), and Edward MacDowell (1860-1908), compositions by contemporaneous artists such Aaron Copland (1900-1990), Henry Cowell (1897-1965), Charles Ives (1874-1974), and Carl Ruggles (1876-1971) were conspicuously absent. In fact, the catalogue listed only one work each from composers George Gershwin (1898-1937) and William Grant Still (1895-1978). Further, Fleisher’s exhaustive search of the European-based publishing houses had produced only nine works by six Latin American composers (see Table 1). The majority of contemporaneous orchestral works penned by composers in the Americas existed only as single unpublished manuscripts.

Table 1. Latin American representation in the 1933 catalogue

- Three Melodies of National Chilean Character (1929)

Published by Maurice Senart

- Marionette: Gavotte (1895)

Published by Leduc and Cie.

- Aubade, op. 10 (1895)

Published by Albert Bock

- Mélodie in F Major, op. 1 (1890)

Published by Schirmer

- Piano Concerto in A, op. 22 (ca.1906)

Published by Friedrich Hofmeister

- Three Cuban Dances (1928)

Published by Senart

- Bembé – Afro-Cuban movement (1928)

Published by Senart

- Suite Sinfonica no. 2 (1920)

Published by G. Ricordi

- Grand Concerto in D Major (1921)

Published by G. Ricordi

Fleisher, along with collection curator Arthur Cohn and head librarian Franklin H. Price, were able to "interest the Government and the State authorities in the desirability of preserving the works of American Composers... copying manuscript scores and making parts of unpublished works by contemporary American Composers."4 "Fleisher assumed the expense for paper, ink, and all other supplies and for transportation and insurance charges on music to and from the composers, while the Library furnished the necessary working quarters and equipment."5 The federal government provided the salaries for project personnel. Officially launched on November 26, 1934, under the Civil Works Administration (CWA)–Local Works Division, the project started with a twenty-one-member staff that included fifteen copyists who completed twenty works before the end of the year.

On April 1, 1935, the library launched a steady flow of invitations to "leading contemporary American Composers" every week—each with a complimentary copy of one of Fleisher’s 700 numbered catalogues and a three-point promise6:

- The works will be available for reference and study by any musician or music lover who visits this Library, including many of the world’s leading conductors, who use the Collection from time to time.

- Works on file in this Collection are insured permanent preservation and in the case of any accident to the original score, the Library’s copy will be available here in case it is desired to consult it or have it copied.

- The music will become a part of the largest and most representative collection of orchestral music in the world and will be properly catalogued and entered in the supplementary list, which Mr. Fleisher will publish at a later date.

By July 1935, the Fleisher Collection had invited some two dozen composers to send manuscript works for copying and had added 118 complete performance sets to the collection. Anticipating the transition of oversight from the state CWA project to the federally managed WPA, Fleisher, Price, and Cohn had begun the application process to continue their work early in July. As can be expected with any bureaucracy, however, processes frequently took priority over results, and governmental wheels turned slowly. All work stopped on July 19 and nineteen copyists were forced to apply for relief. It was not until October 1935 that work resumed under WPA Project 2361. When returning workers grumbled in mid-November over the uncertain conditions of their employment, Price was quick to defend and praise Fleisher’s continued and extraordinary dedication to the collection and its copyists:

Mr. Fleisher occupies a very curious position in relation to this project. First of all, he is the only man in Philadelphia who had faith enough in music to put his hand in his pocket to the tune of $5,000 and buy the supplies you are working with. He comes up here about once a week and he never gets out of this building for less than $20.00. Sometimes it is a hundred.

When this project was stopped during the summer he used all his spare time during nine weeks to get you back to work. He went to Washington, New York, and Harrisburg; he tel[e]graphed and telephoned.

I do not know anywhere else in the city of Philadelphia where I can get an "angel" to underwrite this job.7

The music copying project at the Free Library ultimately operated under nine different identities (see Table 2), and each manifestation required a series of applications and generated literally dozens of documents as Price, Cohn, and Fleisher appealed to myriad administrators to keep this extraordinary venture viable. The inevitable interruptions in work forced Price and Cohn to frequently apologize to and reassure frustrated and befuddled composers over otherwise unnecessary delays. For instance, on September 13, 1938, Price wrote to Aaron Copland:

While it is true that the music copying project scheduled your Music for Radio for completion early in September, the suspension of the project on August 31 unfortunately greatly complicated the Library’s plans and I regret that your work has not been completely finished.

The Free Library, with Mr. Fleisher’s approval, has applied to the government for a new copying project and we trust within the next few weeks to receive word that the application has been approved and that the work has been authorized.8

Table 2. Federal Music Copying Project identities at the Free Library

1176

2361

11960

14564

19795

24086

28383

28908

29345

November 26, 1934 – July 19, 1935, CWA

October 28, 1935 – January 19, 1937, WPA

January 20, 1937 – August 1937

August 1937 – August 31, 1938

October 2, 1938 – January 18, 1940

January 18, 1940 – September 30, 1941

October 11, 1941 – December 3, 1941

December 4, 1941 – June 30, 1942

July 1, 1942 – March 1943

Under the auspices of the WPA, Curator Arthur Cohn spearheaded a racially diverse staff that grew to nearly 100 workers. As word of the project spread, composers began contacting the library to offer their scores, and Cohn noted the impressive swath of genres and composers represented in a 1938 report to WPA administrators:

Representation of each particular phase of composition within the contemporary field has been fulfilled. Among the works copied is the “classic” school represented by such men as Franz C. Bornschein, of Baltimore; Rosseter G. Cole, of Chicago; Felix Borowski, of Chicago; F. S. Converse, of Boston; Cecil Burleigh, of Wisconsin; Wesley La Violette, of De Paul University; Albert Elkus, of California, etc. The “romantic” school contains composers such as Charles Haubiel, of New York; Powell Weaver, of Kansas; Carl Mc Kinley, of Massachusetts; Harold Morris, of New York; Charles Wakefield Cadman, of Colorado; Paul White, of Rochester, etc. The “modern” school is represented by such men as Aaron Copland, of New York; Walter Piston, of Harvard University; Bernard Wagenaar, of New York; Emerson Whithorne, of California; David Diamond, of New York; Edwin Gerschefski, of Massachusetts; etc. The “nationalistic” school is represented by such men as Joseph Achron, of Los Angeles; Ferdé Grofe [sic], of New Jersey; Harl McDonald, of Philadelphia; William Grant Still, of California; etc. Works copied of the “ultra-modern” school are by such men as Henry Cowell, of California; Charles Ives, of New York; Adolph Weiss, of California; John J. Becker, of Minnesota; Roger Sessions, of Princeton University; etc. The works of Philadelphia composers including Otto Mueller, George F. Boyle, Arthur Cohn, etc. have also been copied.9

Fleisher and Symphony Club musical director William Happich jumped at the chance to take the newly acquired works from the page to the stage and introduce them to the community. They selected twenty-five scores, including Paul White’s Symphony in E Minor [2711], Louis Vyner’s Nocturne [2672] and Carl Eppert’s Argonauts of ’49 [2753] to present with the Symphony Club in "a series of six educational broadcasts... in order that the people of Philadelphia may have an opportunity to hear some of the beautiful works which either have never had any performances at all or have had no previous performances in this city." Fleisher convinced local CBS affiliate WCAU to donate a monthly half-hour segment during the 1936–1937 season to carry this series and assured composers "this is not a commercial undertaking and that no one receives any compensation, either directly or indirectly, for the broadcast."10

Aware of the burgeoning behemoth before him, Fleisher declared, "I am of the opinion that a wider and better use of my said Collection could be made."11 Consequently, in 1938 he amended his original Deed of Gift and granted permission for the Free Library to loan works from the collection to performing organizations throughout the world, provided performance material was otherwise unavailable, the composer (or designated representative) granted permission, and no admission fees would be charged for performances. Music from the collection soon became a regular feature at WPA concerts throughout the nation, and Price pointed out that

"Material for performance has been borrowed not only by all the outstanding symphony orchestras of this country and by the three leading broadcasting systems, but also by several European orchestras. More than one thousand works have been lent for performance since 1937... a single work, lent for broadcasting and entered on the Library’s records as one loan, was heard by almost a half million persons."12

A team of eighty professionally trained copyists would add 611 complete performance sets from 295 composers to the collection by July 1939, but Latin American scores remained difficult to come by. Fleisher believed "that no collection of orchestral music could be considered complete without the inclusion of the works of South and Central American Composers... [so he] authorized the Free Library to expand the service into that field."13 Fleisher attracted enthusiastic support from valuable resources such as Brazilian conductor Walter Burle Marx, German-born Uruguayan musicologist Francisco Curt Lange, the Pan American Union, and the Library of Congress. Instant response from the Library’s new partners supplied copyists in Philadelphia with 27 compositions from 24 Latino composers to mark "the project’s enlarged entrance into the field of copying unpublished contemporary South and Central American orchestral music."14 With the blessing of the Division of Cultural Relations of the State Department, Fleisher "sent at his own expenses, Mr. Nicolas Slonimsky, eminent internationally known musicologist to tour throughout South and Central America... for the definite purpose of obtaining the most representative orchestral scores from the leading composers of every country in South and Central America."15 Further, with a monetary prize donated by Samuel Simeon Fels, another prominent Philadelphia philanthropist and adoptive father of violinist Iso Briselli, Fleisher facilitated a Latin American violin concerto competition ultimately won by Camargo Guarnieri.

During 1941, the Music Copying Project added 314 complete works to the collection, including forty-seven compositions by South and Central American composers. Fleisher went so far as to purchase a set of Latin American instruments included in the scores but not typical in U.S. orchestras so they could be lent with the music to facilitate a performance. Overwhelming response to the program, however, had created a significant backlog of work to be completed. The increasing struggle to keep up with incoming manuscripts while losing copyists to an improving economy and subsequent budget cuts added a new set of challenges with the U.S. entry into World War II. Within days of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, letters to Latin American composers began carrying conciliatory caveats:

No doubt you are somewhat concerned by the current war situation, especially as concerns your manuscript scores. Please be assured that the building in which your music is now being copied, is one of the safest in the country. It is made of stone, steel, and concrete and is thoroughly and completely fireproof.16

Sensing the impending threat to funding, Arthur Cohn issued an eight-point confidential memo to defend the program’s value to international affairs and extolling "The Philadelphia Music Copying Project and its share in National Defense."17

It is a definitely ascertained fact that music, in all its forms, plays a very important part in the question of National Defense... The Music Copying Project, sponsored by The Free Library of Philadelphia, is cooperating directly with the Government of the United States in its definite effort to establish and cement cultural relations between this country and the South and Central American Republics... This project’s main purpose is to copy and make available to any recognized American musical organization, the unpublished works (representing 99 1/2% of the total output) of South and Central American composers, in order that such works might be performed in this country.18

Fleisher sought congressional intervention to keep the project running and traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with members of the State Department, Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs Nelson Rockefeller, and the Pan American Union. His appeal to Pan American Union Director Dr. Leo S. Rowe illustrated the problem clearly:

Since Slonimsky’s departure from the United States, the personnel of our Music Copying Project has been gradually decreasing, until we are now at its lowest ebb in the past five years... leaving us with only forty-five copyists, whereas we should have one hundred.

To finish the [346] scores we now have on hand, with our present personnel, would take at least three years; and I am sure that none of the South and Central American composers would be willing to wait that long.19

Renowned New York Times music critic Olin Downes, who in 1939 had resigned as the music director of the New York World’s Fair over the cancellation of classical music for more "popular and low-priced entertainment," pointed out the inherent contradictions and challenges presented in a 1942 New York Times column:20

The discontinuance of this work means the return of scores, which it will be difficult to secure again, a breaking of promises to the composers and the countries concerned—a proceeding not calculated to restore good South American understandings, and the crippling of this part of the collection... [T]he Fleisher Library is constantly lending manuscript scores to orchestra, theatres, ballet organizations and other institutions which could not in any other way secure them.21

In the end, despite continued enthusiastic support from conductors, composers, and cultural leaders from around the world, tightening governmental purse strings slowly strangled the U.S. Works Progress Administration, and the Music Copying Project at the Free Library quietly succumbed in late February 1943, leaving "hundreds of untouched works and several hundred works in various stages of production" and "lacking either a full score or complete set of parts."22 Price summed up the Latin American situation to Charles Seeger, chief of the Pan American Union Music Division, proffering, "Possibly the following summary relating to Pan American Works may be of interest":

Completed and ready for performance: 31

In process of being copied, etc.: 72

Awaiting assignment of trained music copyists: 346

(shown on map sent to you under separate cover)

Received since map was sent to you: 9

Held at Laredo, Texas, Customs House for Clearance: 107

Works which composers have promised to forward: 65, including some already in transit

TOTAL: 63023

Through Fleisher’s unwavering efforts, "A limited number of compositions needed for short wave broadcasts to Latin America were finished with [$8,000]... appropriated by the City of Philadelphia. Scores which could not be copied were microfilmed or photostated, and all of the original manuscripts were returned to the composers who loaned them."24 In addition, he secured the Pan American Union’s cooperation in completing a limited number of Latin American scores selected by consultants Gilbert Chase and Henry Cowell.25

In 1946, the Fleisher Collection published a supplementary catalogue that effectively encapsulated production during the WPA years. It records the addition of "nearly 2,000 unpublished compositions" since 1933, along with a directory of 277 publishers with corresponding agents, and a special section dedicated to 691 works left lacking either score or a full set of parts—"a direct result of the [then] present World War."26 Arthur Bronson, in the American Mercury, placed the collection’s value around this time at $6 million with "[o]ver a thousand works, by 350 carefully selected contemporary composers."27

The scope and success of the WPA Federal Music Project at the Free Library remains unparalleled in music history and helped bring many now-revered composers such as Aaron Copland to international attention. Its seminal role in fostering America’s symphonic coming of age stands out as one the most important events in world music history.

Learn more about The New Deal and see artifacts from the Fleisher Collection in the Free Library's latest exhibition For The Greatest Number: The New Deal Revisited, on view in the William B. Dietrich Gallery, Rare Book Department, Third Floor, Parkway Central Library, Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m., through February 4, 2022.

Footnotes:

1 Lee Fairley, review of The Edwin A. Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music in the Free Library of Philadelphia, Notes (March 1946): 178.

2 Edwin A. Fleisher, "Preface," The Edwin A. Fleisher Music Collection in the Free Library of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Privately printed, 1933), v. Fleisher and crew resourced Karl Geiringer and Alfred Einstein, in part, for biographical data on composers.

3 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to William Manger, Washington, D.C., September 8, 1939, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

4 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to Robert Braine, New York, April 1, 1935, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

5 Franklin H. Price, "Preface," The Edwin A. Fleisher Collection of Orchestral Music in the Free Library of Philadelphia: A Descriptive Catalogue, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Innes and Sons, 1945), 501–2.

6 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to William Manger, Washington, D.C., October 24, 1939, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

7 Price’s statement to workers on WPA Project 2361, November 20, 1935, Fleisher Collection archives.

8 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to Aaron Copland, New York, September 13, 1938, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives. That same week Price sent similar letters to Nicolas Berezowsky, David Diamond, and Granville English.

9 Arthur Cohn, "Report of Music Copying Project, Philadelphia, PA.: Work Project # 14564," March 30, 1938, Fleisher Collection archives.

10 Edwin A. Fleisher, Philadelphia, to Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, July 24, 1936, Fleisher Collection archives.

11 Edwin A. Fleisher, amendment to Deed of Gift, May 3, 1938, Fleisher Collection archives.

12 Edwin A. Fleisher Music Collection, vol. 2, 503.

13 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to Walter Burle Marx, New York, June 21, 1939, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

14 Arthur Cohn, Philadelphia, to Allen D. Quirk, Harrisburg, "Philadelphia Music Copying Project Report for the Year 1941," January 2, 1942, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

15 Ibid.

16 Arthur Cohn writing as Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to José Maria Castro, Buenos Aires, December 23, 1941, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

17 Arthur Cohn, "Philadelphia Music Copying Project Report for the Year 1941."

18 Arthur Cohn, "The Philadelphia Music Copying Project and its share in National Defense," December 30, 1941, Fleisher Collection archives.

19 Edwin A. Fleisher, Philadelphia, to Leo S. Rowe, Washington, D.C., February 12, 1942, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives

20 “Music Program Canceled by Fair: Popular Programs Will Be Substituted for Classical Concerts at Exposition,” New York Times, May 25, 1939, 34.

21 Olin Downes, "WPA Music Project: Though It Is Not Ended, Its Program Has Been Curtailed Seriously," New York Times, May 10, 1942, X7.

22 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to Richard Arnell, New York, October 15, 1942, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

23 Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, to Charles Seeger, Washington, D.C., March 5, 1942, file copy, Fleisher Collection archives.

24 Price, Edwin A. Fleisher Music Collection, 2:502.

25 Charles Seeger, Washington, D.C., to Franklin H. Price, Philadelphia, October 4, 1943, Fleisher Collection archives.

26 Price, Edwin A. Fleisher Music Collection, 2:501, 967.

27 Arthur Bronson, "The World’s Greatest Music Library," The American Mercury 62 (April 1946): 444.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.