Written by Isabel S.

April 23 marks the day that we traditionally celebrate William Shakespeare’s birth and deathday, though neither of those occasions are confirmed to have actually been on the 23rd. Shakespeare was baptized on April 26, 1564, so historians estimate his actual birth was a few days before that. The same holds true for his deathday, which is inferred from his funeral that took place on April 25. At Shakespeare’s funeral there may have been mourners who carried wreaths of rosemary, the herb that begins Ophelia’s famous speech in Act IV of Hamlet.

There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance.

Pray you, love, remember.

And there is pansies, that’s for thoughts …

There’s fennel for you, and columbines.

There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me.

We may call it “herb of grace” o’ Sundays.

—Oh, you must wear your rue with a difference.

There’s a daisy. I would give you some violets,

But they withered all when my father died.

Although Ophelia states that rosemary is for remembrance, it is also a symbol of death and mourning, and so foreshadows her impending death. The flowers, herbs, and plants that Ophelia mentions and gives to the other characters are similarly full of symbolic meaning. Pansies represent sadness, love, and tender feeling, fennel represents flattery, columbines represent fidelity in marriage, and rue represents bitterness and regret. Daisies symbolize innocence and purity, and violets symbolize truth, loyalty and humility, or with their withering, the lack thereof.

Though this scene depicts Ophelia’s descent into madness, there is a consistency and logic to her monologue. Through the symbolism of her bouquet, she speaks to the cruelty, abandonment, and failings of those around her: Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, and Hamlet. The only flower that is mentioned for a specific person is for Ophelia herself. Keeping some rue for herself and giving some to another, she implies that rue means something different to her than it does for the one to whom she gives it.

Shakespeare filled his works with references and imagery of flowers, herbs, and plants. Botanical Shakespeare (Gerit Quealy), a compendium of all the flowers, fruits, herbs, trees, seeds, and grasses mentioned by Shakespeare, states that Shakespeare made over 170 references to plants and flowers. Elizabethan audiences would have been familiar with their various cultural, medicinal, and spiritual uses and meanings, especially since many flowers, plants, and herbs would have been found in their home vegetable and herb gardens. However, much of this folklore knowledge is lost to the average modern audience member, though they may know the symbolism of a flower here and there.

Symbolic meaning can be conveyed in other ways, though. Without any specific description within the text of Ophelia’s monologue (besides rue for herself), the staging of this scene is dependent on the director and actors who will have to convey what it means to give columbine to someone like Gertrude who marries her husband’s brother and murderer to an audience that probably doesn’t know that columbine, ironically, means fidelity in marriage.

It is an ambiguity like this within the text of Shakespeare that enriches the experience of watching a play performed rather than just reading it. Shakespeare is famously sparse with his stage directions (“exit, pursued by bear” notwithstanding). Instead, directors and actors are left to make decisions for how to stage and deliver scenes like this, emphasizing certain themes, sympathizing with certain characters, or infusing irony into the text. It is nothing new to say that the best way to experience Shakespeare is aloud. To see a play performed, to act yourself, or simply to read the lines aloud by yourself or with friends is to find that the language comes alive, jokes are made more apparent, puns are discovered, and the rhythm of iambic pentameter felt.

There are other ways to engage with Shakespeare’s works, however. We may not know all of the meanings attached to the flowers and plants that Shakespeare referenced, but it is possible to engage with them through the senses. It is possible to see “the many-colored Iris,” taste “sweet honeysuckle,” and test whether a “rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” To do so is an invitation to explore and discover new meaning in these phrases. If you’ve ever cooked with rosemary, then you know how potent its smell is and how long it lingers on your fingers. What then, does it mean to say “rosemary, that’s for remembrance,” or to twist a branch of rosemary into a wreath to throw into a grave? Perhaps it means that even after someone is gone, they still remain with you in the scent on your fingers and the memories in your heart.

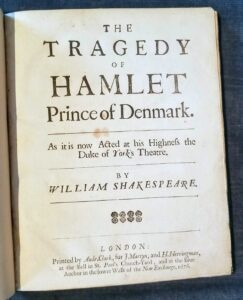

Dr. Rosenbach’s Shakespeare collection originally included copies of all four folios and the first quarto (single) edition of each play; these were sold to Martin Bodmer in 1952, but The Rosenbach still retains a rich collection including second (2 copies), third, and fourth folios, one first quarto (Merchant of Venice, 1609), and about 140 later editions, mostly single plays from the late 17th and 18th centuries. The Rosenbach’s garden, the only original one remaining on the block, has also been planted with a number of the flowers and herbs that Shakespeare referenced in his works. To see The Rosenbach’s collections you can make a free research appointment online, or view the garden on your next visit to The Rosenbach. You can also check out The Rosenbach’s garden guides online.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.