A Continued Discussion on the Topics of Surrealism and Gender

By AdministratorWritten by Lewis Shaw, who conducted extensive research in the Art Department as part of a Friends Select School Senior Internship Project. The following is a continuation of a previous blog post on the topics of Surrealism and Gender.

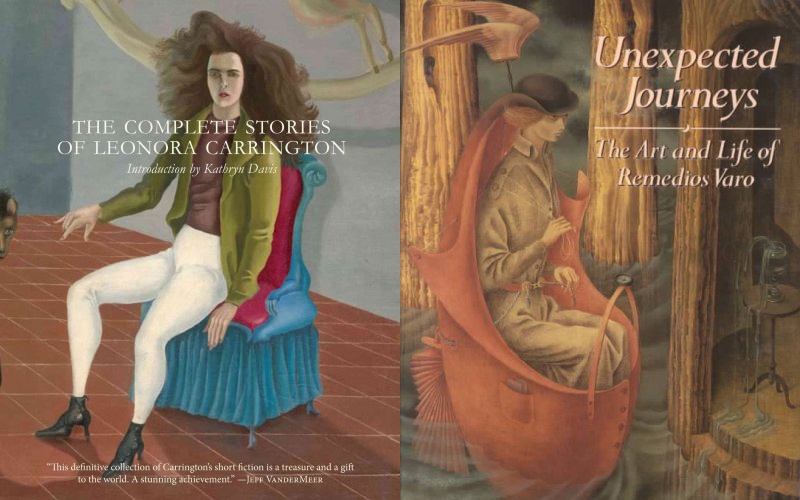

Leonora Carrington grew up in the UK as the daughter of a rich couple whose wealth was built on the textile industry. As a child, she was fascinated with folktales and Irish myth, which appears quite often in all of her work. Her relationship with her parents was strained, particularly with her father. One needs only to read her short story, "The Oval Lady", to understand her feelings concerning him. She was expelled from every school that her family tried to keep her in, but, at the age of 18, she was allowed to go to art school where she worked under the painter Amédée Ozenfant at his exclusive and expensive academy, where she was rigorously taught technical art skills.

After discovering the Surrealist Movement, she met and fell in love with Max Ernst in 1937, running away from her life as she had known it to join the movement. Though Carrington vehemently rejected her role as a muse and held herself in the same place as the male artists of the movement, she was seen as Ernst’s Femme Enfant and treated with a sort of incredulous reverence by her male colleagues. She would later separate from Ernst following his detainment, and after fleeing their country home, she was incarcerated in a Spanish mental asylum where she was forcibly given the drug Cardiazol, which induces episodes of seizure. This was essentially shock therapy.

Following this episode of traumatic pseudo-medical, abusive treatment, Carrington was never quite the same, and over the next few years, she was yet again under the control of her family, being transported from institution to institution, completing scant writings and drawings here and there. She did eventually escape from her family and moved to the United States, and then to Mexico, where she spent the rest of her artistic career. Her work is fantastical, influenced by those such as Hieronymus Bosch, and incorporates a plethora of personal symbolism, derived from the events of her life.

Carrington’s absolute rejection of the Femme Enfant concept was ultimately what caused her split from Ernst, as she realized the relationship wasn’t what she wanted and that it didn’t allow her the artistic freedom that she desired. Her work uses the female form as a symbol of strength, motherhood, and mysticism. Quite possibly her most famous piece, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), is a triumph of femininity in artwork and completely antithetical to the Femme Enfant. In the piece, Carrington sits in the right half of the canvas, situated in the corner of a room. The composition of the edges of the two walls, ceiling, and floor spreading out from Carrington’s outstretched hand presents the viewer with a sense of absolute control over her surroundings. Seated in a vaguely vaginal chair, Carrington exudes feminine power. Next to her is a mother hyena—in her collection of short stories, Carrington briefly trades places with a hyena to escape a debutante ball—with three teats and a set of eyes eerily similar to Carrington’s. Her hand gestures towards the hyena, perhaps in an effort to establish a mutual understanding of their places in the painting, which continues the dialogue of the usage of women in painting.

Born in Spain in 1908 to a relatively wealthy family, Remedios Varo’s childhood was relatively idyllic. She enjoyed the pleasures of nature and understanding parents. Her father was encouraging of her love of art and would take her to museums, teaching her technical art skills. Against her will, she was forced by her mother into catholic school at a young age, but after her father observed her artistic aptitude, she was sent to schools of the arts in Madrid at the age of 12. After flourishing at art school, she’d go on to marry Gerardo Lizarraga, a Spanish political activist and artist, in 1930.

Fleeing political unrest following the founding of the Spanish Republic, she and Lizarraga went to Barcelona, where Varo would seek France and the surrealists. She started seeing another man, Esteban Frances, which marked the beginning of Varo’s polyamorous lifestyle. Varo immediately began making art in the vein of surrealism and associated herself with the artist and writer Marcel Jean, who served as she and Frances’s link to the surrealists of Paris. Through Jean, she met Paul Eluard, and Benjamin Peret, who she would fall in love with while married to Lizarraga and involved with Frances. In 1937, she left them both and moved to Paris to join Peret.

Similar to Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington, Varo, a young and undeniably beautiful woman (though she was in her thirties, much older than Carrington), was Peret’s Femme Enfant. After moving to Paris, she was welcomed into the inner circle of surrealism through her connection to Peret, meeting Breton, Paalen, Brauner, Ernst, and Dali, among many others. While living with Peret, she became involved with Victor Brauner. Varo was now not seen as just the Femme Enfant, but as a woman of her own and who was seemingly magnetic to the artists around her. So while she was no longer an Enfant, this period of her artistic life was quite varied and did not involve any traceable style other than the subject matter and compositions she chose. Varo was known for living a wild life with a multitude of lovers at a time, and her art reflects this constant change. Like an explorer charting new territory, Varo experimented with all the new tools and techniques at her disposal. Varo would soon have to leave Europe to flee the nazis and would find a new home in Mexico, where she would remain good friends with Carrington.

Remedios Varo’s work is recognizable on account of its recurring fantastical imagery and mythic inspirations. Her work contains both male and female forms and uses them in both narrative and allegorical ways. A good example of this is her 1936 painting, L’agent Double (Double Agent), which features two figures, as the name might suggest, but also a disembodied crimson hand and a wall of human breasts. The main figure is androgynous and faced against a wall with their nose pressed into the left side of the painting. On their back is a massive insect, which seems to be whispering into their ear or sucking them dry through their neck. The second figure is all but completely obscured by a crevice in the floor. Only their forehead and hair poke through. The wall of breasts, painted like a marble statue, is situated opposite of the viewer on the back wall, and at its bottom is a small tree, suggesting pubic hair and a vaginal form. The aforementioned crimson hand is extended from a hole in the right wall and holds what looks to be a sperm cell. Both of the figures are faced away from the hand and the breasts. This composition can be interpreted as a commentary on the female form’s role in art. The wall of breasts is representative of the constant objectification and reduction of the female form into what male viewers and artists want to see. However, Varo subverts this expectation by turning the figures in the painting away from the wall, and neither of them seems at all interested in the masculine hand, either.

Throughout this project, I was struck both by how far the world of art has come in terms of equal representation and treatment of people of all gender identities, but also by how much still must be done. When you ask the average person about the surrealist movement, they’ll know Dali, they’ll know Picasso, maybe Ernst and Duchamp will come up, and they might even be able to name a couple of paintings by them. But if you ask them about female surrealists, they’ll probably jump to Frida Kahlo (who didn’t self-identify as a surrealist), but they almost definitely won’t be able to name another.

The reason I did this project was because I needed to educate myself, and I want to be able to educate others about this as well. More people should know about artists like Toyen, Meret Oppenheim, Louise Bourgeois, Kay Sage, and so many more. Look them up. Read something about one of them. Come into the Art Department and talk to Alina. If you’re reading this blog post, you have the resources to educate yourself—you can do it!

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.