In their search for freedom of conscience and worship, as well as for the promise of economic self-sufficiency and inexpensive land, many German-speaking Christian sectarian groups emigrated to Pennsylvania from the late 17th century onwards. Some of these pietists organized themselves into communal societies under the direction of charismatic leaders. Best known of these are the Ephrata Cloisters under Conrad Beissel and the Moravians under Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf. Both communities sought autonomy and separation from the outside world, while developing self-supporting profitable economies. In every case these people emphasized the arts and crafts, especially music. They emulated David and his singing praises unto God with the timbrel and harp (See: Psalm149: 3). They also remembered that Apostle Paul had exhorted Christ’s followers in Colossians 3:16 to “…let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord.”

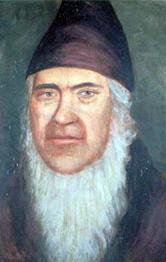

It is, therefore, not surprising to find music as a focal point of another pietistic group, the Harmony Society, founded by the charismatic leader George Rapp (1757-1847). The Harmonists established three successive settlements: They first moved to Butler County, Pennsylvania in 1804. There they created a thriving communal village named Harmony. In 1814 the town was sold at a considerable profit. Everyone moved west to Indiana where they again prospered in a communal setting, also known as Harmony. Circa 1824 the members sold this enterprise to Richard Owen, who renamed it New Harmony. George Rapp and his followers then returned to Pennsylvania establishing the village of Economy in Beaver County, which also proved to be economically very successful. However, because members took vows of chastity, the group inevitably dwindled in numbers. In 1905 upon the death of its last adherent, the Society ceased to exist. Its vast real estate holdings were sold principally to the American Bridge Company, which enlarged the town, and incorporated it as Ambridge.

The chief recreation of the Harmonists was music. Every member of the Society had some training, and almost every one could play a musical instrument. They celebrated Christmas, Easter, and Good Friday, as well as their own Harmonie Fest (Founder’s Festival), Danksagungstag (Day of Thanksgiving), and Liebesmahl (Lovefeast). At each of these celebrations music played a prominent part, and elaborate programs were arranged for them. Also, quite often during times of planting or harvesting, the members would conduct hymn writing contests among themselves. In some instances the winning hymn was printed for use in future celebrations.

The Borneman Pennsylvania German collection is fortunate to have several of the Harmony Society’s manuscripts and imprints. Especially noteworthy is Borneman Manuscript Nr. 101, Gertrude Rapp’s (1808-1889) Liederbuch. She was the founder’s granddaughter, and was an active, and especially enterprising member of the Harmony Society. An accomplished pianist and singer, Gertrude was the only female Harmonist who studied an instrument.

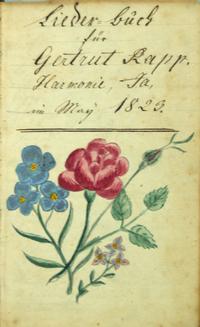

The bookplate in her Liederbuch contains her name, location, and date in German, i.e. Songbook for Gertrut Rapp. Harmonie, Ia [Indiana], in May 1823, along with a lovely Fraktur example of a hand-drawn spring floral bouquet with red roses, blue and pink quatre foils done in watercolors. The songbook contains many original composed pieces celebrating, among others, Christmas (Auf den Christtag A.D. 1822, 121), the Harmony Fest (Ode Auf das Harmoniefest A.D. 1822, 111, Aufs Harmoniefest 1823, 123); Easter (Ostern 1856, 128-131). Many songs contain the word “Harmony” in varying contexts. An astounding number praise the beauty of nature, and focus exclusively on the harmonists’ appreciation of the natural beauty surrounding them. For example Seht Gespielen, seht die Flur (See, my Playmates, See the Meadows in Full Bloom…8-10) rejoices in springtime more in the style of a secular song than a hymn. Another Nur Thoren verachten den Bauern stand… (Only Fools Despise Tillers of the Soil, 67-68) seems more a declaration of a secular creed than religious sentiment.

Before the Society began printing its songbooks, the members wrote personal collections of their songs into strongly bound blank books such as Gertrude’s. In 1820 Heinrich Ebner of Allentown, PA printed the first Harmonist songbook entitled “Harmonisches Gesangbuch.Theils von andern Authoren, Theils neu verfasst.” Zum Gebrauch von Singen und Musik für Alte und Junge. Nach Geschmack und Umständen zu wählen gewidmet. Allentown, Lecha County, im Staat Pennsylvanien. Gedruckt bei Heinrich Ebner, 1820 (Harmonist Songbook, Containing a Partial Selection of Other Authors’ Works and a Selection of Original Compositions. To Be Sung by Old and Young Alike, and To Use According to One’s Own Taste and/or Per the Occasion, Allentown, Lehigh County in the State of Pennsylvania. Printed by Heinrich Ebner, 1820). The Borneman Fraktur collection has a copy of this first edition with a bookplate, now part of the FLP Fraktur Digital collection, FLP B-70, which translated reads: This Songbook belongs to David Lenz, Harmonie [IN], February 2, 1823. Please note that Gertrude started her songbook in May of 1823, and the Fraktur inscription for David Lenz, a member of the Harmony Society, is from February 1823.

Upon comparison of the registers from both works, there don’t appear to be any shared hymns. However, the Harmony Society printed the second edition themselves at Economy in 1827, and it is here that we find Gertrude’s nature-oriented manuscript pieces in print: Du hoher schwarzer Thannenwald (You Lofty Stand of Dark-hued Pine); Der Greiss des Silberhaares (The Old Man With the Silver Hair); Wie des Lenzen milde Lüfte (How the Mild Breezes of Spring…). Gertrude collected 52 songs, of which circa 25% are included in the second edition of the Harmonist Songbook of 1827. Her choices reflect a happy spirit who sings of God’s presence in all of nature.

Gertrude possessed many talents, and, like her step uncle Frederick Rapp (1775-1834), proved to be a very smart and adept entrepreneur. In 1827 at age 19, she took an avid interest in raising silkworms and the manufacture of silk fabrics. Since the Harmonists were master weavers, and already had a highly developed and profitable textile business, it made sense to investigate the pros and cons of adding silk to their cotton, linen, and woolen products. Gertrude invited silk specialists to teach her all the details of silk production. She also learned how to care for silkworms. Through repeated experimentation, effective techniques for reeling silk were developed. Within a few years the Harmonists were producing five to six thousand pounds of cocoons annually, and from this manufactured silk, ribbon, brocade, velvet, and satin. Their products were of very high quality, and their business grew, peaking in the 1840’s. When the U.S. government refused to grant them a protective tariff from foreign competition, they ceased production in 1852. They realized to continue would be unprofitable. For twenty-five years, Gertrude Rapp not only managed the production of silk goods equal to or superior to the European silk imports, but also was the gracious hostess to many important personalities, who came to Economy, Pennsylvania to learn about their techniques and experiences with silk.

Please be sure to visit our Facebook gallery for more images of Gertrude Rapp’s Songbook, Borneman Manuscript 101.

Preservation of the Free Library of Philadelphia's Pennsylvania German manuscript collection has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Because democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.