Sarah Horsfield (1785-1867)

Sarah Horsfield (1785-1867), was the oldest daughter of Joseph Horsfield (1750-1834) and Elizabeth (1754-1836) née Benezet, and was born December 17, 1785. She had two younger sisters.

Her grandfather Timothy Horsfield (1708-1773) emigrated to Long Island in 1725, and after he married Mary Doughty, a young Quaker, opened his home to Moravians who were passing through his area. In December 1741, the Horsfields were honored to host Count von Zinzendorf on his first night in America. Horsfield’s family and he moved to Bethlehem on October 28, 1749. Timothy served as Justice of the Peace and Colonel of Northampton County during the French & Indian War.

Sarah shared her mother’s same special love for hymns, and hymn texts. Elizabeth’s children wrote in her Memoir, the original of which is in English: “…She would frequently and with peculiar emphasis repeat her favorite hymn, ‘O tell me no more of this world's vain store...’ ”[A hymn by John Gambold, a Welsh Moravian]

Joseph, Sarah’s father, was the youngest of eight children, and was born in Bethlehem November 24, 1750. He served as a Justice of the Peace, Notary Public, postmaster, and as superintendent of the first bridge to be built over the Lehigh River. He also was a member of the Aufseher Collegium, which was the board of supervisors overseeing Bethlehem’s businesses. He enjoyed being active in the musical life of the congregation, and served as an organist for the services on a regular basis.

After completing her studies at the Moravian Female Seminary, Sarah taught there from 1804 to 1819. When her parents needed someone to look after them, their oldest daughter gladly took the responsibility, caring for them with special love and attention until their deaths—her father in 1834, and her mother in 1836. She then took up residence in the Sisters House for thirty-one years. Sarah was very close to God, and walked with Him in a way noticeable to all who came into contact with her. Rev. Edmund de Schweinitz who presided over her funeral wrote, the original of which is in English: “…Her knowledge of hymns was extraordinary, &. in her long & lingering illness of many months, she often gave expression to her faith by repeating the songs of Zion. Even when her mind wandered, hymns would recall her to a sense of Christ’s presence.”

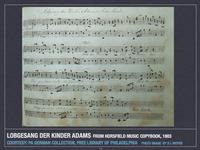

Sarah Horsfield Music Copybook, July 14, 1803

The Sarah Horsfield Music Copybook, 1803 contains thirty-seven vocal pieces, all of which are in German, except for three, which are in English. The Lieder, songs, and arias are for solo voice with indications sometimes for a section to be sung by chorus, or as a duet. The themes are worship; God in nature; nature; mourning; remembrance; [songs of] thanksgiving; friendship; hope; and consolation.

Five excerpts from Der Tod Abels (Death of Abel) are found in Sarah’s Music Copybook, and shed light on the changes in musical culture at the turn of the nineteenth century both on the Continent and in America. In 1762 when the Moravian communal system was abandoned in favor of a cash economy, key Moravian families of independent means began to pay musicians to copy music for them. The Nazareth General Store Ledger, 1795-1806 includes, among many others, an entry in 1798 for copying the piano-vocal score of Johann Heinrich Rolle’s Der Tod Abels.

Rolle’s (1716-1785) fame was assured when he provided the music for Der Tod Abels, a sacred drama (1769) by Johann Samuel Patzke (1727-1787). Rolle was then musical director in Magdeburg and much respected by his fellow musicians, especially Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814), Royal Prussian court conductor (Kapellmeister) to Frederick II. It was Salomon Gessner (1730-1788), one of the most internationally popular writers of his day, who wrote the original religious epic Der Tod Abels (1759). His Idylls (1756) and the Death of Abel were both quickly made available in English. They appealed to the pietistic sentiments in Europe and America; consequently were reprinted many times; and remained popular up to around 1825 when literary tastes changed. Patzke acknowledged that he used Gessner’s work as his model. It was, however, Rolle’s music rather than the weak writing of Patzke that carried the day, and assured the work’s popularity. In fact, it so enchanted the public that Bernhard Christoph Breitkopf quickly brought out a piano-vocal score, to be used at home by aficionados of serious music for their personal enjoyment. Rolle responded on June 12, 1776 to Breitkopf about producing a new edition: “Leave it as it is. It [the original edition] has survived its critics; has been in demand; and remains in demand. I have proof of this from the many personal inquiries I receive for orders.”

Both the Moravian inventories and music copybooks from 1780 onwards support the observation that Moravians were current with the musical and literary scene in Europe. Young women of a certain class and background were expected to be well-schooled in music and skilled in playing the clavier, not only for the domestic enjoyment of fine music within their own homes, but also in the unforeseen event that they needed to financially support themselves. As we have seen with Rolle and Der Tod Abels, music publishers were very quick to take advantage of this and published piano-vocal scores of current popular music, whether classical or otherwise, for private use. They, as well as the Moravians, saw a financial opportunity, and both astutely restructured how they did business in order to capture this unique and profitable market. The Bethlehem schools expanded their already enviable music programs to include both current sacred and popular music, and packaged them for the prominent Moravian families and outside affluent families, who would expend whatever monies were necessary to educate their daughters in the finest manner at the prestigious Moravian day and boarding schools.

Perhaps Sarah’s already knew what destiny had in store for her when she inscribed a poem on the front flyleaf of her “Music Copybook, 1803” entitled “Das Clavier” by the poet Christian Felix Weiss,(1726-1804). In my translation, it reads:

Sweet sounding Clavier, What joy you give to me. In my solitude how amusing you can be; As I direct, so you become, One time inspirational, Another time lighthearted fun. If I am happy, let sound a cheerful lay; If I am full of grief or pain, my hurt allay. When I begin to sing some pious songs, How much do you me then inspire. So may my breast n’er ope itself to false desire, My joys be pure, that they my strings will be, And my whole life resound with sweetest harmony !

Charlotte Sabine Schropp’s and Sarah Horsfield’s were contemporary to one another, and led similar lives. Both

• were born into well-to-do, prominent Moravian families, Sarah in 1785, and Charlotte Sabine in 1787.

• must have known each other.

• must have attended the Female Seminary together.

• owned manuscript music copybooks.

• subsequently taught at the Female Seminary.

• forfeited married life.

• became primary caregivers and devoted their whole lives to loved ones.

Conclusion

The three Moravian manuscripts presently part of the Henry Stauffer Borneman Pennsylvania German collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia are valuable assets to researchers and to the general public. They furnish a detailed view of the sacred traditions and secular changes in the lives of the Moravian communities and individuals at the turn of the 19th century, as well as views of a lost early America, both its landscapes and people’s lives. The constant and unchanging element has always been the music, which was the lifeblood of Moravian life then and continues to be so now.

• The Theodor Schulz Diary, 1785-1844 will be available in a forthcoming publication I am presently preparing. It will be annotated. Plans are for it to contain the original old German script, a transcription, and English translation, making it a very practical resource.

• Clavier und Singstücke für Charlotte Sabine Schropp, January 1799 will soon be digitized, and available online.

• The Music Copybook of Sarah Horsfield, July 14,1803 will be available to scholars and the general public at the FLP Rare Book Department.

Please be sure to visit our Facebook gallery for more images of these three Moravian manuscripts ~ Borneman Mss. 117, 142, 143.

For additional related Moravian resources, please visit the Moravian Archives website.

Preservation of the Free Library of Philadelphia's Pennsylvania German manuscript collection has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Because democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.