A Book of Hours takes its name from the so-called “Little Hours of the Virgin,” a collection of eight prayers that is derived from the Divine Office—the canonical hours observed by persons who have taken the orders of monks, nuns, or priests. Matins is at 3:00 AM, Lauds is at 6:00 AM, Prime is at 9:00 AM, and so on. The Hours of the Virgin is the heart of a Book of Hours, but the book will also include a calendar, excerpts from the Gospels, an Office of the Dead, a Litany, Suffrages to saints chosen by the individual, and other texts. The Book of Hours was the “bestseller” of the Middle Ages from roughly the end of the 1300s until the 1500s. It is the most common medieval book represented in libraries today, and the Free Library of Philadelphia is home to dozens of them.

This manuscript was made sometime between 1460 and 1480 for a wealthy merchant named John Browne, who lived in Stamford, Lincolnshire. It was made in Flanders, and at that time, there were a number of places in Flanders called “ateliers” that would make Books of Hours for individuals all over Europe, especially people living in England. The Browne Hours is a very traditional-looking Book of Hours—in earlier years, most Books of Hours would have belonged to members of the nobility. But John Browne was a member of a newly arrived successful class of noveau riche or very successful bourgeoisie, who may have long admired the handsome books of the noble class his entire life, and probably sent off for his manuscript to be made when he could finally afford to do so.

The Browne Hours is best-known for its binding, an original, fifteenth-century binding by Anthony de Gavere, a member of a prominent family of Flemish bookbinders active from 1459 to 1505. His name is recorded in the inscriptions stamped into the borders of the four decorative panels on the front and back covers. The two clasps that contain miniatures depicting the Virgin and Child with an angel (upper) and St. Veronica holding the Sudarium (lower) are inscribed on the reverse with the names of John and Agnes Browne to further personalize the manuscript for its owners.

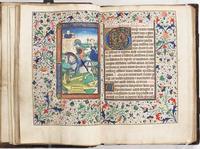

A particularly English miniature in this manuscript is that of St. George, one of the patron saints of England.

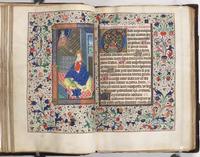

One of the fun miniatures in this manuscript is of St. Margaret. It looks as though someone has tried to erase her face. In fact, it’s most likely that many women in possession of this manuscript kissed the face many times, effectively blurring it. St. Margaret was swallowed by a dragon and escaped alive when the cross she was carrying irritated the dragon’s insides. St. Margaret, for that reason, is the patron saints of women in childbirth.

Here is a link to this codex in our medieval manuscripts database online. Every image scanned from the book has a thumbnail (NB: the entire codex is *not* scanned).

Stay tuned for the second part of stories about this manuscript, involving the English Reformation!

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.