Drop by any library and look at some picture book covers. Every color, shape, age, and gender smile back at you, but are they really representing diversity? What and who define diversity? How has our understanding of diversity changed and grown over the years? Are educators, librarians, and the publishing industry getting it right?

Not quite, but we’re getting better. An organization called We Need Diverse Books is working to improve the situation. Here’s their definition of diverse books:

We recognize all diverse experiences, including (but not limited to) LGBTQIA, Native, people of color, gender diversity, people with disabilities*, and ethnic, cultural, and religious minorities.

*We subscribe to a broad definition of disability, which includes but is not limited to physical, sensory, cognitive, intellectual, or developmental disabilities, chronic conditions, and mental illnesses (this may also include addiction). Furthermore, we subscribe to a social model of disability, which presents disability as created by barriers in the social environment, due to lack of equal access, stereotyping, and other forms of marginalization.

Positive representation of diversity in children’s books has developed slowly. Mid-19th century readers had only didactic stories of well-behaved white Christian children—and The Bible—to read to and with children. It was 100 years after the Civil War before positive representations of diversity started appearing on picture book pages.

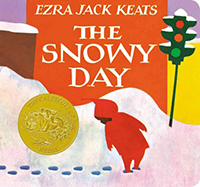

The Civil Rights Movement and Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a wake-up call for librarians and the book industry. The American Library Association awarded the 1963 Caldecott Medal to Ezra Jack Keats for The Snowy Day, which features a black child in a city landscape.

The Civil Rights Movement and Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a wake-up call for librarians and the book industry. The American Library Association awarded the 1963 Caldecott Medal to Ezra Jack Keats for The Snowy Day, which features a black child in a city landscape.

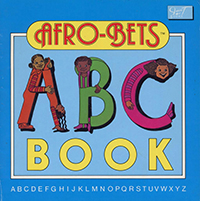

But in the Sixties, depictions of African-American children, positive or stereotypical, was the exception. Urban League Executive Director Whitney M. Young Jr. complained about Golden Books’ 1963 title, A Visit to the Children’s Zoo, which was populated with only white children, and in his syndicated column To Be Equal, lamented stereotyping in books in general. As late as the 1980s, African Americans were still struggling to get published. Wade and Cheryl Hudson self-published their first book, Afro-Bets, after several years of shopping it around. Their publishing house, Just Us Books, is still going strong.

But in the Sixties, depictions of African-American children, positive or stereotypical, was the exception. Urban League Executive Director Whitney M. Young Jr. complained about Golden Books’ 1963 title, A Visit to the Children’s Zoo, which was populated with only white children, and in his syndicated column To Be Equal, lamented stereotyping in books in general. As late as the 1980s, African Americans were still struggling to get published. Wade and Cheryl Hudson self-published their first book, Afro-Bets, after several years of shopping it around. Their publishing house, Just Us Books, is still going strong.

Librarians and academics have been keeping track of the numbers. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has collected and published statistics on books published by and about people of color since 1985. The titles cover the broad spectrum of children’s subjects, including books that would have no people in them: animals, astronomy, etc. That first year, CCBC discovered that of the 2,500 children’s trade books published, 18 were written and/or illustrated by African Americans. In 2015, of the 3,200 U.S.-published books received by CCBC, 105 were by African Americans, 9 were by American Indians / First Nations, 156 were by Asian Pacifics / Asian Pacific Americans, and 56 were by Latinos. In other words, people of color were only responsible for the content of 10% of children’s books, while the U.S. Census reported that in 2014, over 50% of children under the age of 5 were of racial and ethnic minorities.

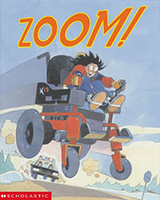

Positive depictions of diversity go beyond race and color. One of the few books about physical disability available at the Free Library for years was Howie Helps Himself (1975), featuring a wheelchair-bound boy with cerebral palsy. The major criticism is that the book focuses mainly on what Howie can’t do. A generation later, we focus on endless possibilities. Zoom! (2003) by Robert Munsch features a girl in a souped-up wheelchair who rescues her injured brother.

Positive depictions of diversity go beyond race and color. One of the few books about physical disability available at the Free Library for years was Howie Helps Himself (1975), featuring a wheelchair-bound boy with cerebral palsy. The major criticism is that the book focuses mainly on what Howie can’t do. A generation later, we focus on endless possibilities. Zoom! (2003) by Robert Munsch features a girl in a souped-up wheelchair who rescues her injured brother.

The LGBT community has also had a hard time getting children’s books on the market. A year after Just Us Books began publishing, the iconic Heather Has Two Mommies by Leslea Newman and Laura Connell was published thanks to a Kickstarter-like effort. LGBT representation in children’s books has been miniscule, but things are changing. As well as books for older children, picture books now feature single-parent families of both genders and children facing gender challenges.

The LGBT community has also had a hard time getting children’s books on the market. A year after Just Us Books began publishing, the iconic Heather Has Two Mommies by Leslea Newman and Laura Connell was published thanks to a Kickstarter-like effort. LGBT representation in children’s books has been miniscule, but things are changing. As well as books for older children, picture books now feature single-parent families of both genders and children facing gender challenges.

Homosexuality is also addressed in the animal kingdom. And Tango Makes Three is the fictionalized story of two male penguins at the Central Park Zoo who raise a chick together. The book is now available in board book format, which traditionally is marketed to the toddler set, indicating that publishers recognize there’s a market for the subject.

Homosexuality is also addressed in the animal kingdom. And Tango Makes Three is the fictionalized story of two male penguins at the Central Park Zoo who raise a chick together. The book is now available in board book format, which traditionally is marketed to the toddler set, indicating that publishers recognize there’s a market for the subject.

Visit the Association for Library Services to Children’s blog for more statements on diversity and inclusion. You can also read the Free Library’s recent statements on our commitment to diversity, equality, and inclusion. Also, check out We Need Diverse Books’ great book recommendations. And finally, stop in at your local neighborhood library and talk to the Children’s Librarian!

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.