The Free Library has recently mounted an exhibit of treasures from our collections that illustrate the history and artistry of the comic book medium. This display can still be seen on the 2nd-floor landing and the Art Department gallery at the Parkway Central Library through June 15 and then its contents will once more be available to the public.

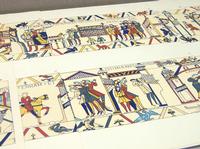

The idea of presenting a narrative through a consecutive series of images has a very long history. A portfolio of prints based on drawings of the Bayeux Tapestry, made by the artist Charles Alfred Stothard in the early 19th century, presents an early predecessor to the comics. The original embroidered work was created in the 11th century and documents important historical events. The story is told vividly in about 60 captioned panels of images and contains character development and thrilling plot twists. Another visual storytelling technique familiar to readers of comics is the use of additional sequences above and beyond the main narrative. Many of these are decorative and depict plants, animals, and fantastic creatures, but some present additional brief, sometimes bawdy, narratives. Stothard's drawings were first published in the 1820s as etchings. This portfolio, however, published by the Pageant Book Company in 1855, owes its richness of color to the screenprinting technique and can only be truly experienced in person.

Mesoamerican pictographic narratives are another example of a kind of proto-comics. Relatively few have survived destruction at the hands of invaders and they are long scrolls of sophisticated graphic sequences. The library holds several complete early facsimiles of these works. Two of these are the Mixtec Codex Fejérváry-Mayer and the Aztec Boturini Codex, contained in this volume.

Narrative picture scrolls, or emakimono, have a long history in Japan. The set of four scrolls collectively known as the Chōjū -giga, are thought to have been created in the 12th century. One is a farcical tale with frogs, monkeys, and rabbits as its protagonists, told entirely in images. The facsimile held by the Free Library reproduces the famous first scroll in actual-size, 1 foot high and 36 feet long, as a folding book. No digital substitute can replace the physical experience of examining these long, accordion-folded books in person.

Other examples of accordion books in this exhibit include The Great War by Joe Sacco, the progression of a single day in a wordless 24-foot-long folded panorama, and The Tooth-ache, a humorous tale written by Horace Mayhew and illustrated by George Cruikshank. Our hand-colored copy of The Tooth-ache was printed in 1849, in Philadelphia.

Other examples of accordion books in this exhibit include The Great War by Joe Sacco, the progression of a single day in a wordless 24-foot-long folded panorama, and The Tooth-ache, a humorous tale written by Horace Mayhew and illustrated by George Cruikshank. Our hand-colored copy of The Tooth-ache was printed in 1849, in Philadelphia.

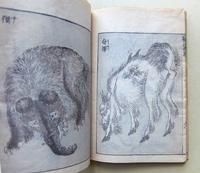

The Manga series is among the many works created by prodigious Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. The term has become synonymous with comics in Japan but it was at the time understood to describe whimsical sketches. Hokusai’s drawings were converted into woodcuts by printmakers and printed in three colors. The Free Library of Philadelphia holds a complete 15 volume set of the Hokusai-Manga from 1875. They are printed from the woodblocks and bound in the fukuro toji style.

The Manga series is among the many works created by prodigious Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. The term has become synonymous with comics in Japan but it was at the time understood to describe whimsical sketches. Hokusai’s drawings were converted into woodcuts by printmakers and printed in three colors. The Free Library of Philadelphia holds a complete 15 volume set of the Hokusai-Manga from 1875. They are printed from the woodblocks and bound in the fukuro toji style.

The Swiss artist Rodolphe Töpffer is widely celebrated as the first creator of comics in the modern sense. All of Töpffer’s comics, originally published between 1837 and 1846, have been conveniently collected in one volume.

The Virtuoso, published in 1865, was one of many prints created by German cartoonist Wilhelm Busch for the Münchener Bilderbogen, or Picture Sheets from Munich, a series published by the Braun and Schneider firm. Many artists contributed and their drawings were transformed for printing by Kaspar Braun, who was a skilled wood engraver. They were sold as individual sheets or in bound annual volumes and a full set of these is held in our collections. Selections by certain artists like Busch have been reproduced elsewhere but only the experience of a full volume of this influential publication can provide appropriate context.

French comics, or bandes dessinées, are to this day most commonly found in the same standard size albums as the ones that collected the 19th-century work of Caran d’Ache. The artist prefigured another major trend in the medium of comics: his strong "clear line" drawing style would be later famously used by artists like Hergé, the creator of Tintin.

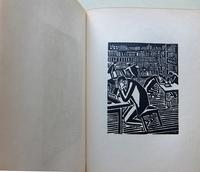

The Flemish artist Frans Masereel published dozens of wordless novels. His first major work in the genre was My Book of Hours, a novel-length story of a single character's life journey. It was popular in Europe when it was first published in 1919 but not distributed abroad until 1922. The library holds a copy of that first English-title version, one of an edition of 600 books printed directly from the artist's woodblocks and signed.

The Flemish artist Frans Masereel published dozens of wordless novels. His first major work in the genre was My Book of Hours, a novel-length story of a single character's life journey. It was popular in Europe when it was first published in 1919 but not distributed abroad until 1922. The library holds a copy of that first English-title version, one of an edition of 600 books printed directly from the artist's woodblocks and signed.

Lynd Ward, the American who further popularized "pictorial narratives"—to use his own preferred term—published six works in between 1929 and 1937. His inspirations were the wordless novels Destiny by Otto Nückel and The Sun by Frans Masereel. Several early editions of Ward's works can be requested in the Art Department.

The term "graphic novel" was first used by Will Eisner to describe his 1978 work A Contract with God, as a way to imply that the book was both meant to be taken seriously and intended for an adult audience. The graphic novel—that "ungainly neologism"—in the words of Art Spiegelman, is not always novel-length work, just as comics are not necessarily humorous.

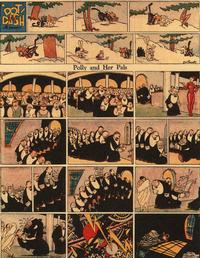

Comics can be browsed on the shelves of the Philbrick Hall graphic novel collection as well as those of the Art Department. Volumes that reproduce or discuss the pioneering work of artists such as George Herriman, Lyonel Feininger, and Jackie Ormes can also be borrowed, but many more are available by request for use in the library. Beautiful but bulky and sometimes rare and fragile volumes of work by artists such as Albert Guillaume, Chris Ware, and Gary Panter can be easily enjoyed by library users who visit the Art Department in person.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.