For Baby Boomers, the words “Land Shark”, “Samurai Delicatessen”, “Coneheads”, and “The Blues Brothers” conjures up adventures on the wild frontier of comedy, when Saturday Night Live defined the ultimate in pointed, no-holds-barred laughs that weaved back and forth on the tightrope between blistering satire and taboo-busting offensiveness. But for people who came of age in the early '90s, that special magic is conjured by the words “Homey D. Clown”, “Handi-Man”, “Fire Marshal Bill”, and “The Homeboy Shopping Network”.

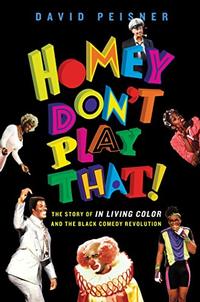

If you’d like the backstage dish on the revolutionary show that put the African-American experience at the forefront of sketch comedy, then swing by the Arts and Literature department and pick up the book Homey Don’t Play That! The Story of In Living Color and the Black Comedy Revolution.

The half-hour sketch show often described as "The black Laugh-In" was the brainchild of Keenen Ivory Wayans, the second of ten children born to Elvira and Howell Wayans in Harlem, New York City. He and his siblings – a crew that included other eventual performers Damon, Kim, Shawn, and Marlon Wayans – grew up poor but self-reliant in the projects, amusing each other with made-up games like "Make Me Laugh or Die" or pranks like ringing a fake phone bell to make their mother run to get the call, only to hear a dial tone. The fact that this sparked verbal fireworks between their parents – she was convinced he was seeing another woman who hung up when she answered – only added to the fun. "[Our parents were] the best buddy comedy ever," recalled Marlon Wayans. "[Forget] Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny. We got to watch Elvira and Howell."

But their mother also loved Richard Pryor and would wake Keenen up to see the comic she called "that little skinny boy" perform on late night television. (If you’re not familiar with Pryor’s unflinching brand of caustic observation and profane vulnerability, the library has several DVDs of the best of his stand-up, including Richard Pryor Live on the Sunset Strip and Richard Pryor: Live in Concert.) In 1976, when Keenan was still a teen, Pryor had enough counterculture clout to be courted by Saturday Night Live’s producer Lorne Michaels to host their seventh episode, but the comedian had a list of demands, including that the musical guest be Gil Scott-Heron ("The revolution will not be televised") and that his writer Paul Mooney (later of Chapelle’s Show) write for the show that week. The resulting broadcast was such a success that NBC gave Pryor a prime-time special, as well as a 10-episode sketch comedy series – but the series was too controversial and ahead of its time to last more than four shows.

The idea of a similar, fiercely unapologetically black comedy show wasn’t on Keenan Ivory Wayans’ mind yet, but he was thinking more seriously about becoming a comedian himself. In 1978, while he was on summer break from Tuskeegee Institute, he performed a set at New York’s comedy club The Improv. He bombed, but the thrill of being on stage lit a fire underneath him. He recalled his parent’s reaction when he sat the family down to announce he was dropping out of his engineering program to become a comic full-time: "I might as well have said I was going to smoke crack."

The second half of Homey Don’t Play That includes much about In Living Color’s backstage drama, its battles with censors, and its legacy in launching the careers of Jamie Foxx, Tommy Davidson, Damon Wayans, David Alan Grier, Jim Carrey, Rosie Perez, Kim Coles, and Jennifer Lopez. But its first half is the most eye-opening about how a self-created, self-sustaining community of black comedians and actors banded together to create opportunities in an industry that relegated them to stereotypical roles.

Keenan was friendly with Eddie Murphy and Arsenio Hall before they got their big breaks, and was active in the all-black comedy troupe The Kitchen Table, whose members supported each other’s rise in Hollywood. He and Robert Townsend co-wrote the self-financed satire Hollywood Shuffle together as a way of creating the kind of roles they wanted instead of just waiting for Hollywood.

Whether he and his siblings were pranking their mother or creating a game-changing comedy show that made room for Chapelle’s Show and Key & Peele, Keenan Ivory Wayans knew the support of peers is what makes things possible.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.