Interior Chinatown and Philadelphia’s Chinatown: Intersecting Stories

By Terence W.One Book, One Philadelphia is officially in full swing!

We had the kickoff on April 20 with Interior Chinatown author Charles Yu tuning in from his home in California. I encourage you to check out the podcast of our conversation. We discussed his characters, writing his way through difficult feelings, his parents’ establishment of a Taiwanese-language school, and what it means to read such a specifically Asian-American story in diverse groups. (Freelance curriculum writer Rachel Toliver wrote about that beautifully here on the blog.)

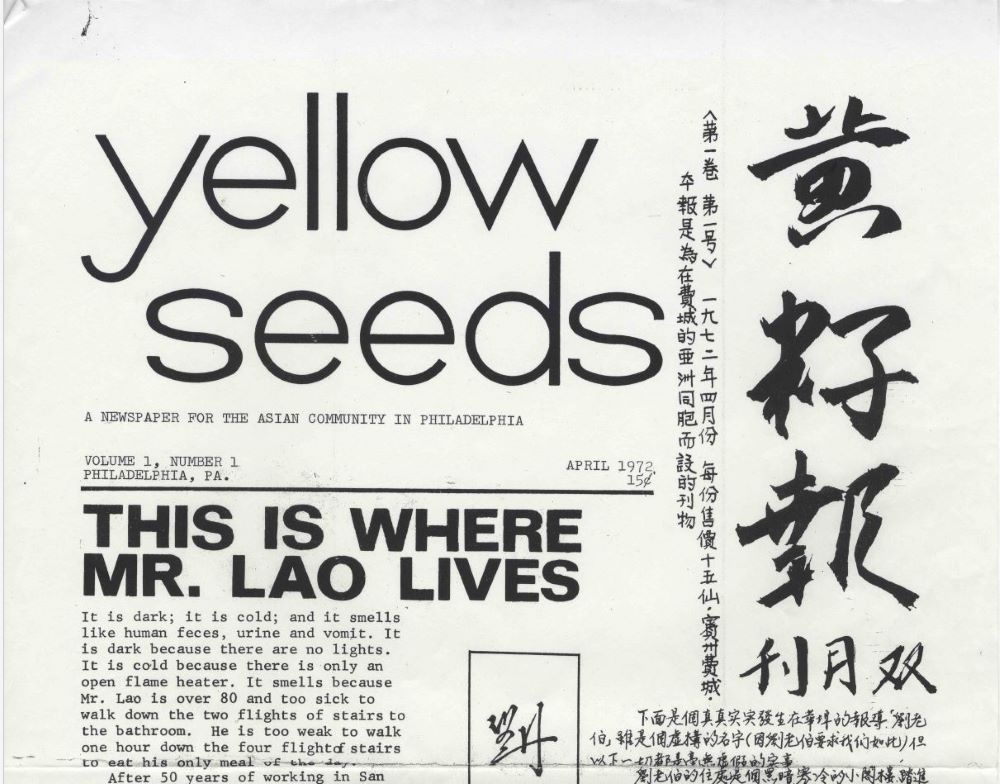

We’re excited for next week’s panel conversation with activists Mary Yee, cofounder of Yellow Seeds; Debbie Wei, cofounder of Asian Americans United; and Taryn Flaherty and Kaia Chau, cofounders of Students for the Preservation of Chinatown. The panel will happen on Wednesday, May 10, at 6:30 p.m., in the Skyline Room at Parkway Central Library. The event is free to attend, but registration is required.

Why would we invite activists to speak when we’re reading a novel without activism in it? Two big reasons, really...

For one thing, Interior Chinatown deals explicitly with the "American Dream" and the ways immigrants from Asia and Black Americans, in particular, have tried to realize it for themselves. At a certain point, I began to read it as a book about trying to get free from the belief that the American Dream is simple, real, or for everyone. These have been concerns in Philadelphia’s Chinatown and other areas of the city for generations. If anyone works explicitly to try and get a bit freer all the time, it’s activists. Much like Charles Yu’s parents, members of Philadelphia’s Asian Americans United started the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures School (FACTS) in Chinatown in 2005. FACTS has taught a generation of students by now, including Kaia and Taryn, now college students and activists themselves.

Secondly, there’s a heartbreaking moment in the book where Old Fong, who resides in a one-room apartment and lives for his weekly call with his son, dies from a fall while rushing from the shower to pick up his son’s phone call. The lives of elders in the Chinatown community have consistently been held up as important by people in the neighborhood. In the inaugural issue of the Yellow Seeds’ eponymous newspaper in 1972, they reported on an 80-year-old man they called “Mr. Lao,” who lived essentially in squalor in a building in Chinatown and far away from his impoverished family back in China. Mr. Lao’s story animated the Yellow Seeds, who arranged for weekly cleanings and donations of food, working to keep him in Chinatown when the city’s help would’ve isolated him elsewhere in Philadelphia. They also implored young people to take care of their elders. Not quite a year later, Mr. Lao, who eventually died, was eulogized beautifully, and five of the eight people at his funeral were Yellow Seeds. In a similar way, the residents of Old Fong’s building in Interior Chinatown come together to support Young Fong when he comes to clean out his father’s apartment after his death. Interior Chinatown and the Yellow Seeds point to the importance of elders and how the American context can affect their well-being and relationships with others.

In the kickoff conversation with Charles Yu, I shared the biggest takeaway I’ve had from Interior Chinatown and my research into Charles' career and his concerns as an author. Phoebe, the daughter of the main character Willis Wu, feels key for me as the youngest character of the book and the granddaughter of immigrants from Taiwan. She speaks English and Chinese (or Taiwanese, it’s unclear); lives in the suburbs; and, most importantly, she stars in her own television show, Xie Xie Mei Mei. In at least one specific way, Phoebe is like her father. We see from Yu’s description of Xie Xie Mei Mei that Phoebe is heavily influenced by television and her family’s history. It’s a cartoon, sort of. Real people against an animated backdrop, a show about a little Chinese girl, Mei Mei (little sister), and her adventures in a new country. The country is geographically unique and logically impossible — some amalgam of dynastic China, a Taiwanese village in the olden days (before imperial colonizers!), and some focus-group-tested, aesthetically engineered, perfect mythical U.S. suburb — an optimistic amnesiac’s retelling of the age-old story of immigration, acculturation, and assimilation.

A major difference between Phoebe and Willis is that Phoebe is the star and writer of her own show. Xie Xie Mei Mei comes from her synthesis of her family’s history and culture — unlike the child-free world of Black and White, in which Willis is a side character in a world organized around a Black/white racial dichotomy. For me, the book builds to a big, unanswerable question: given all these potential influences, what will Phoebe’s life be like?

Having an intergenerational panel of activists here allows us to approach, though maybe not answer, questions like that one. What have the Students for the Preservation of Chinatown learned from AAU and the Yellow Seeds? How has their formation been made possible by the ways the Seeds and AAU have made Philadelphia better? How did they learn what they needed to become such important voices in Philadelphia’s civic discourse? I’m curious, and I’m excited to learn about how the Yellow Seeds, Asian Americans United, and Students for the Preservation of Chinatown developed their organizations and found their voices, which continue to be indispensable to Chinatown and to Philadelphia.

Register online for the Activism in Philadelphia's Chinatown panel discussion, to be held on Wednesday, May 10 at 6:30 p.m. at Parkway Central Library.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.