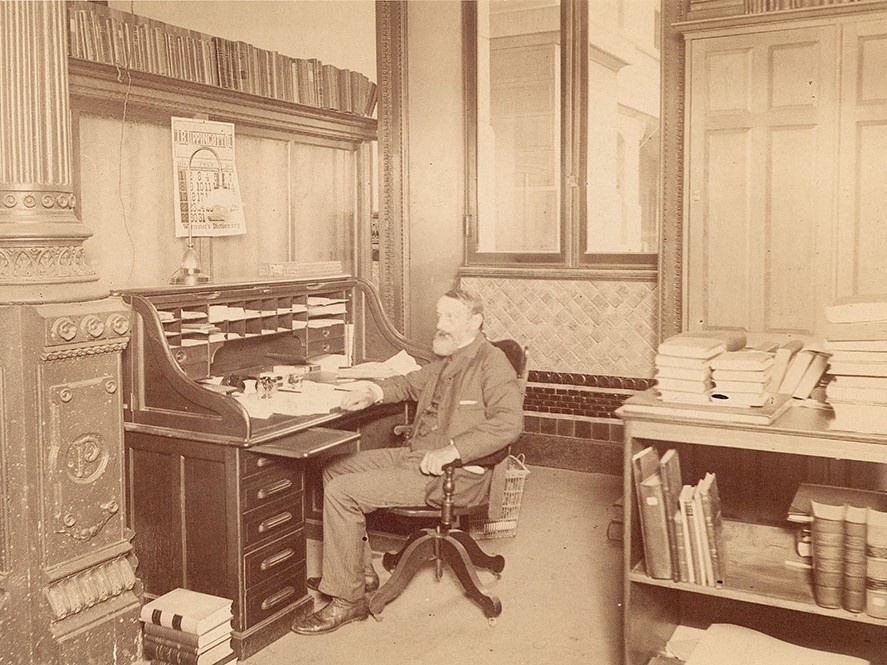

For over 130 years, the Free Library has been serving the communities of Philadelphia. Because we believe that history is important and should be shared, we are working to make the Free Library of Philadelphia Archives an accessible and sustainable collection.

By "archives," we mean the records (documents, photos, recordings, and more) the Free Library has created that have continuing historical value for researchers. These records preserve evidence of the actions and decisions of the Free Library, as well as its impact on communities and the library profession.

Broadly the Archives documents the history and development of the Board of Trustees, divisions, departments, offices, and staff; central and branch locations; public services and engagement; major projects; and planning. This story is told through annual reports, department and divisional reports, meeting minutes, correspondence, photographs, architectural renderings, publications and promotional materials, objects, scrapbooks, studies and surveys, and more.

Eventually, the Archives will be open to staff and the public with questions large and small, complex and specific. The documents in the Archives can answer questions like "What were the salary grades of library workers at the Free Library in 1952?" but also spark further questions about how the Free Library has reflected and influenced local, state, and national communities.

A few examples from the Archives are included below:

In the early 20th century, Philadelphia experienced an outbreak of smallpox. A 1903 letter from the Director of Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health and Charities, Edward Martin, to the President of the Free Library’s Board of Trustees, Joseph G. Rosengarten, is a primary source demonstrating how libraries react to public health issues:

Between World War I and World War II, librarians debated intellectual freedom and the extent to which books and other materials should represent all points of view. In 1939, the American Library Association (ALA) codified its commitment to intellectual freedom and privacy in the ALA Code of Ethics. Still, after the United States entered World War II, librarians would have to balance their commitment to intellectual access and privacy against support for the Allied Forces. In 1942, the War Department issued an order through the ALA to libraries to restrict certain materials. In the memo below, the Director of the Free Library, F.H. Price, asked staff to limit materials on explosives, secret inks, and ciphers, and to send the names and addresses of patrons who asked for them to the FBI. The document can support research on libraries’ later reactions to the Cold War and other conflicts in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The excerpt below comes from a Construction Progress Report, written in August 1966 by William McConkey, Chief of Administrative Services at the Free Library. In addition to the Central Library Parking Area, projects were underway for the Girard Avenue, Roxborough, Welsh Road, Fox Chase, Knights Road, Lehigh, Torresdale, Greenwich, and Oak Lane neighborhood libraries, as well as the air conditioning system in the Rare Book Department at Parkway Central Library.

The need for space for library buildings, patrons, and staff has been a constant concern throughout the history of the Free Library. Documents like these can develop questions about how public buildings affect local communities and serve those communities in the future.

In 1973, Congress passed the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities in federal employment and in programs and services that received federal aid. Later in the decade, in 1978, the Free Library laid off 20 percent of its staff during a budget crisis. One of the first cuts was the Homebound Services program, which delivered Library materials to people who could not leave their homes. The Free Library then started to develop a volunteer program to deliver materials. As this effort was underway, the attorney Harriet Katz filed the document below on behalf of Disabled in Action of Pennsylvania and their members, which argued that they had been excluded from access to Library services provided by the Free Library. The document can illustrate how the Library has responded to the needs of patrons and the advocacy groups supporting them.

The excerpts above are only a few examples of what is currently in the Free Library of Philadelphia Archives, and can only begin to explain the Library’s history.

Although the Archives are a rich resource, they will continue to grow and will need ongoing maintenance. We aim to fully process the Archives, meaning organizing, preserving, and describing the collection to get it ready for researchers and create guidelines that will aid the future collection of material from Free Library staff, departments, divisions, and branches.

In the meantime, if you have any questions about the Archives, email Bill Robinson, Special Collections Curator for Archives at robinsonb@freelibrary.org.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.