ALs to Mrs. Cropper

Charles DickensItem Info

Physical Description: [9] pages

Material: paper

Transcription:

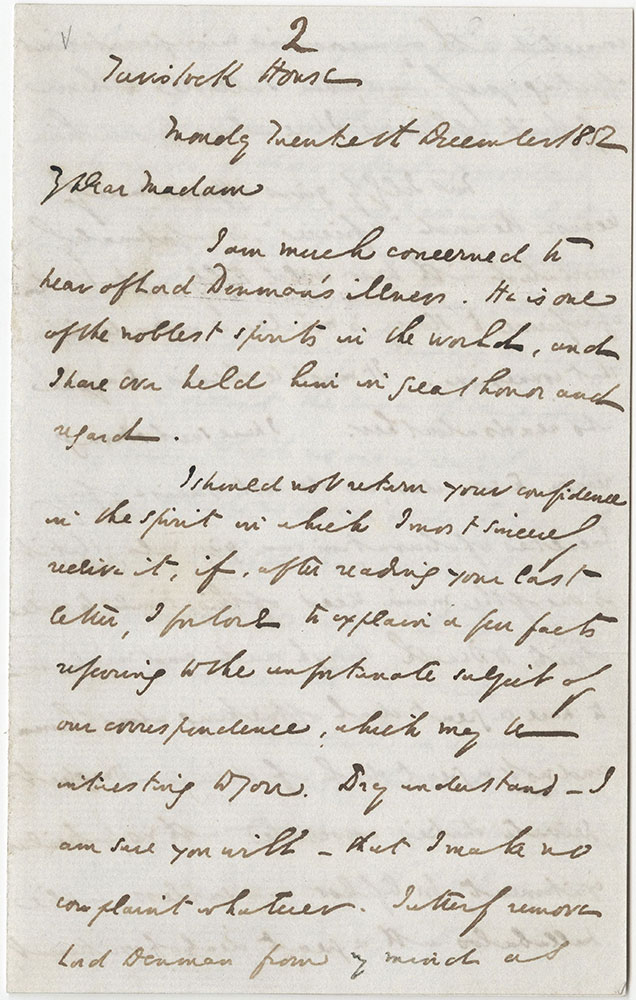

Tavistock House

Monday Twentieth December I852

My Dear Madam,

I am much concerned to hear of Lord Denman's illness. He is one of the noblest spirits in the world, and I have ever held him in great honor and regard.

I should not return your confidence in the spirit in which I most sincerely received it, if, after reading your last letter, I forbore to explain a few facts referring to the unfortunate subject of our correspondence, which may be interesting to you. Pray understand-I am sure you will-that I make no complaint whatever. I utterly remove Lord Denman from my mind as connected with any unconscious misrepresentations affecting myself, and, when I allude to them, only think of him as I have always known him.

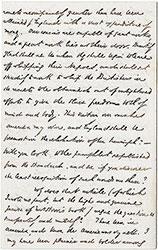

Mrs Jellyby gives offence merely because the word "Africa", is unfortunately associated with her wild Hobby. No kind of reference to slavery is made or intended, in that connexion. It must be obvious to anyone who reads about her. I have such strong reason to consider, as the best exercise of my faculties of observation can give me, that it is one of the main vices of this time to ride objects to Death through mud and mire, and to have a great deal of talking about them and not a great deal of doing-to neglect private duties associated with no particular excitement, for lifeless and soulless public hullabaloo with a great deal of excitement, and thus seriously to damage the objects taken up (often very good in themselves) and not least by associating them with Cant and Humbug in the minds of those reflecting people whose sympathies it is most essential to enlist, before any good thing can be advanced. I know this to be doing great harm. But, lest I should unintentionally damage any existing cause, I invent the cause of emigration to Africa. Which no one in reality is advocating. Which no one ever did, that ever I heard of. Which has as much to do, in any conceivable way with the unhappy Negro slave as with the stars.

In the article on slavery in Household Words, there is this emphatic conclusion. "Americans might so abolish slavery as to produce with little or no cost-probably with profit to themselves-results incomparably greater than have been attained by England with a vast expenditure of money. Our cousins are capable of great works, and a great work lies at their door. Heartily glad shall we be when they shall begin to leave off whipping their Negroes, and shall set steadily to work to whip the Britishers in the results to be obtained out of enlightened efforts to give the slave freedom both of mind and body. This victory over ourselves America may win, and England shall be foremost in the celebration of her triumph."-Will you look to the pamphlet republished from the Standard, and see if you discover the least recognition of such words as these?

Why does that article (of which I wrote no part, but the high and genuine praise of Mrs Stowe's book) argue the question so temperately and mildly? I have been in America, and know the Americans very well. I may have been plainer and bolder among them on this question-at all times steadily refusing, even in the slave districts, to compromise it or gloss it in the least-than most English travellers while there. Of that, I say nothing. But the American slave owners are an extremely proud and obstinate race-I suppose the most obstinate race on the face of the Earth. If I wanted to exhibit myself on this subject ,I know perfectly well that a few pages of fiery declamation in Household Words would make their way (wafted by the Anti-Slavery Societies) all over the civilised earth. But I want to help the wretched Slave. Now I am morally certain that when public attention has been called to him by pathetic pictures of his sufferings and by the representation in deservedly black colors of his oppressors the way to save him, is, then to step in with persuasion and argument and endeavour to reason with the holders, and shew them that it is best, even for themselves, to consider their duty of abolishing the system. I can imagine nothing more hopeless than the idea, while they are smarting under attack, of bullying or shaming them. You might as well fire pistols at the Alps. Further than this, I apprehend there will soon be a war in Europe. The only natural alliance for England then, is with America. If the slavery issue should then be so full of green wounds as to hold America aloof, I think I plainly see that the great man of our people will say, "we have thrown this great and powerful friend away for the sake of the Blacks"-and that the Blacks will for a long time afterwards have a very small share of popular sympathy. All these points I-take into consideration to the best of my ability, wrong or right.

The pamphlet complains of my calling Mrs Stowe's book, a work of fiction. I believe I have done my part in presenting truths under the guise, but I never heard my books called by any other name, and I never wrote that I was mortally aggrieved or injured by their bearing that designation. To say of Mrs Stowe's book that it has "occasion al overstrained conclusions and violent extremes" is a great offence. But I call it a very overstrained conclusion and a very violent extreme, and a damaging absurdity to the slave himself, to set up the Colored race as capable ever of subduing the White. I pointed this out to Mrs Stowe herself, who replied to me that she had not that intention. In her execution, however, I still think it to be there. But greatly admiring the book, and highly sympathizing with its purpose, I entered into no details of objection but enthusiastically commended it. I have been assured on reasonably good authority-Mrs Stowe's-that she was animated to that task by being a Reader of mine. It is not very reasonable-do you think it is?-to turn it as an angry weapon against me.

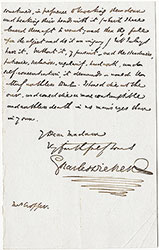

The pamphlet, being angry with me on these wholly mistaken grounds, objects that I come in at the Death of Chancery and might have attacked it before. The most serious and pathetic point I tried with all indignation and intensity to make, in my first book, (Pickwick) was the slow torture and death of a Chancery prisoner. From that hour to this, if I have been set on anything, it has been on exhibiting the abuses of the Law.

I have no right to say exactly four words of objection to Uncle I have no right to say exactly four words of objection to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (amidst the most ardent praise of it) because I converted Mr. Scrooge by a Christmas Dinner. It is as much a fact as the Docks at Liverpool—for there is a printed book which cannot be unprinted—that I converted Mr. Scrooge by teaching him that a Christian heart cannot be shut up in itself, but must live in the Past, The Present, and the Future, and must be a link of this great human chain, and must have sympathy with everything. Suppose I were to take it into my head to claim to have converted Mr. Scrooge by a street doorkey, or a patent Mangle, or an Elephant, or a Monkey. Could I possibly, while the print and paper lasted, alter the fact in the least?

Pray do not, therefore, be induced to suppose that I ever write merely to amuse, or without an object. I wish I were as clear of every offence before Heaven, as I am of that. I may try to insinuate it into people’s hearts sometime, in preference to knocking them down and breaking their heads with it (which I have observed them sometimes to resent,--and then they fall upon the object and do it an injury) but I always have it. Without it, my pursuit—and the steadiness, patience, seclusion, regularity , hard work, and self-concentration, it demands—would be utterly worthless to me. I should die at the oar, and could die a more contemptible and useless death in no man’s eyes than my own.

My Dear Madam

Very faithfully yours

Charles Dickens

Mrs. Cropper.

MssDate: Monday Twentieth December 1852

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Recipient: Cropper, Mrs.

Provenance: Gift of Mrs. D. Jacques Benoliel, 12/6/55.

Bibliography:

Harry Stone "Charles Dickens and Harriet Beecher Stowe," Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Vol. 12, No. 3 (Dec., 1957), pp. 188-202

Volume 6, pp. 824-828, The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Madeline House & Graham Storey ; associate editors, W.J. Carlton … [et al.].

Country: Creation Place Note:Tavistock House

Country:England

City/Town/Township:London

Call Number: DL C883 1852-12-20

Creator Name: Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870 - Author

ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper  ALs to Mrs. Cropper

ALs to Mrs. Cropper