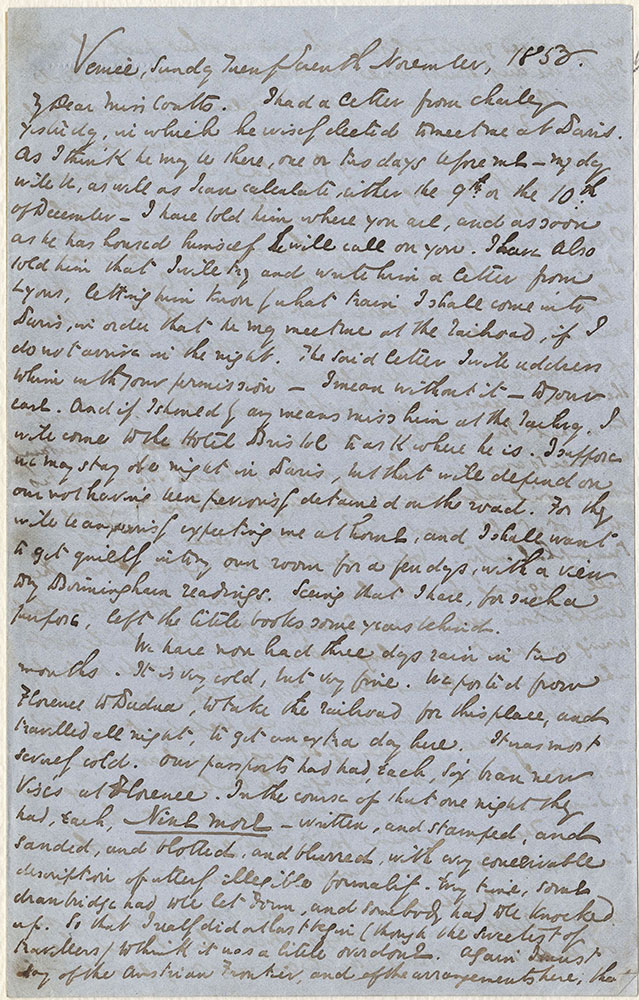

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

Charles DickensItem Info

Physical Description: [4] pages

Transcription:

Venice. Sunday Twenty Seventh November, 1853.

My Dear Miss Coutts. I had a letter form Charley yesterday, in which he wisely elected to meet me at Paris. As I think he may be there, one or two days before me--my day will be, as well as I can calculate, either the 9th. or the 10th. of December--I have told him where you are, and as soon as he has housed himself he will call on you. I have also told him that I will try and write him a letter from Lyons, letting him know by what train I shall come into Paris, in order that he may meet me at the Railroad, if I do not arrive in the night. The said letter I will address to him with your permission--I mean without it--to your care. And if I should by any means miss him at the Railway, I will come to the Hotel Bristol to ask where he is. I suppose we may stay one night at Paris, but that will depend on our not having been previously detained on the road. For they will be anxiously expecting me at home, and I shall want to get quietly into my own room for a few days, with a view to my Birmingham Readings. Seeing that I have, for such a purpose, left the little books some years behind.

We have now had three days rain in two months. It is very cold, but very fine. We posted from Florence to Padua, to take the Railroad for this place, and travelled all night , to get an extra day here. It was most severely cold. Our passports had had, each, six bran new Vises at Florence. In the course of that one night they had, each, Nine more--written, and stamped, and sanded, and blotted, and blurred, with every conceivable description of utterly illegible formality. Every time, some drawbridge had to be let down, and somebody had to be knocked up. So that I really did at last begin (though the sweetest of travellers) to think it was a little overdone. Again I must say of the Austrian Frontier, and of the arrangements here, that we experienced greater politeness than in any other part of Italy; the duty strictly done, but the doers of it, being treated like gentlemen, invariably responsive, explanatory, and courteous.

For our prodigious sojourn of four days, we have established a highly imposing Gondola, rowed by two men in a modestly alarming livery, who are very strict in observing all the old stately forms. Last night we proceeded to the Opera in our gallant bark, with an enormous--Christmas Pantomimic--lantern in the prow. When we landed, the chief of our two Gondolieri went before, with this terrible machine, and lighted us--not only up to the Theatre door, but up the Staircase, through the brilliantly lighted passages (where the lantern became a mere twinkle) and into the box. I don't know that I ever in my life felt more absurd, and I certainly was never so anxious to shave anybody as I was to shave my two companions: whose moustaches, being in their feeble in fancy, did not at all accord with the magnificence of this triumphal entry. What I suffered all night, from the fell misgiving that the lantern would reappear, or what temptations were upon me to drop into the pit, I will not wring your heart by describing. But at the end of the ballet, when there was still another act of the Opera to come, I opened the box door a very little way, and peeped out--with the intention of sneaking away if the coast were clear. The instant I looked into the passage, the lantern--beaming and radiant--burst out of a corner and blazed into the box again! There was nothing for it but to go back in the same State. I saw nobody laugh; which was my only comfort.

Everything here and elsewhere, of the beautiful kind, looks as I left it nine years ago. Except that I found the old ruins of Rome (the Coliseum excepted) smaller than my imagination had made them in that space of time. I went to see Lockhart at Rome, where, as perhaps you know, he is passing the winter. He is dreadfully changed, even in his changed state, and I should think his recovery very very doubtful. Yet he was cheerful about himself too, after we had walked to and fro in the sunlight a little while, and spoke of himself as "going to be better."

I am sorry to see that there have been some disturbances in Lancashire, arising out of the unhappy strikes. I read in an Italian paper last night, that there had been symptoms of rioting at Blackburn. The account stated that the workers of that place, supposing some of the obnoxious manufacturers of Preston to be secreted "nel palazzo Bull" assembled before that Palazzo, and demanded to have them produced; and that thereupon, "La Signora Lawson, padrona del palazzo Bull", appeared at a window and assured the crowd that they were not within. I suppose the Palazzo Bull to be the Bull Hotel, but the paragraph gave no hint of such a thing.

(I wish you would come to Birmingham and see those working people on the night when I have so many of them together. I have never seen them collected in any number in that place, without extraordinary pleasure--even when they have been agitated by political events).

Among the vast mulltitude of beggars we have seen, there came up one, at nightfall--at a poor little place on the Roman side of Siena--carrying another, a disabled youth--and very heavy--on his back. After begging in the usual manner, and with great volubility for some time, and getting nothing (nobody having any small money of the country) he suddenly jerked his burden into a dirty little doorway, and walked off. The burden tumbled down like a sack of flour, and lay there, apparently quite used to it. I suppose he is picked up whenever a carriage is seen coming, and thrown away when there is nothing going on. Another beggar at the same place persisted so long (we were Waiting for horses) that I remonstrated, and said, "My good man I have told you twenty times that I have no little money. Why do you take so much trouble in vain? Why don't you go home and get to bed?"-- "Sir", said he, "I'll give you change"--"Well, but if you can give me change, you can't be very poor."--"O yes I am. I have not eaten for five days"--"And still got change in your pocket?"--"Truly, yes, what is a man to do? I must keep change, for English travellers. English Travellers are my only property, and they never have change.

Although the Grand Canal is undeniably romantic, and the window at which I am writing (close to the Piazza of St. Mark) has a noble view of it, my feet are so intensely cold that I must take them to the fire. The unromantic wind is blowing from the East, and, there being a crack in the wooden part of the balcony casement (prodigiously picturesque from the outside) through which I can see the whole of the Trieste Steamboat with a very dirty Turk on board, I am, fortunately for my "gentle reader", prevented from going on into another sheet. Which I had had serious intentions of doing.

My kind regards to Mr. Brown, and to O. Pray mention to the latter that I am collecting some materials for a pitched battle with her on my return. I expect to be dreadfully puzzled by some of your specimans of the curious game when I am so happy as to see you all again.

Ever Dear Miss Coutts

Most Faithfully Yours

Charles Dickens

MssDate: Sunday, Twenty Seventh November, 1853

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Notes:

Record created by BZ.

Recipient: Burdett-Coutts, Angela Georgina

Provenance: Christie's sale 8536 11/8/96, Benoliel Fund.

Bibliography:

The Letters of Charles Dickens, Pilgrim Edition, Volume Seven, pages 212-214.

Country: Country:Italy

City/Town/Township:Venice

Call Number: DL B897 1853-11-27

Creator Name: Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870 - Author

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts  ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts  ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts

ALs to Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts