How much of an author’s own life is represented in their books? This thought occurred to me as I was working on Virginia Lee Burton’s collection, processed though a CLIR grant for the Children’s Literature Research Collection. My fellow archivists on this project are both lucky to work with amazing collections that allow them to really get to know the authors. The collection I recently finished processing was different because it focuses solely on one book and reveals little about Virginia Lee Burton as a person.

Most people recognize Virginia Lee Burton’s work because she wrote the perennial favorite Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel in 1939. Burton was a Caldecott award-winning author and illustrator who originally trained as a dancer and designer. She began writing children's books to entertain her sons. Her first book, Jonnifer Lint, was about a piece of dust. Though the book was never published, it helped her learn a lot about writing for children when she tried to read the story to her 3-year-old son Aris, who fell asleep! Soon, though, she had commissions as an illustrator and began writing and illustrating her own books about subjects slightly more entertaining than dust, such as trains (Choo Choo: The Story of a Little Engine Who Ran Away, 1937), traveling houses, (Little House, 1942), rustler-foiling horses (Calico, the Wonder Horse, 1941), and adventurous snow plows (Katy and the Big Snow, 1943).

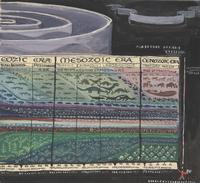

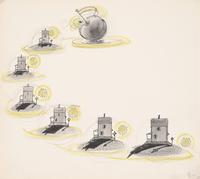

Her final book, Life Story (1962), is the one represented in our collection. It took her eight years to perfect it, and examining the meticulously executed drafts of the book tells you why it took so long. Our collection includes literally hundreds of drafts and sketches that were eventually refined into the 67-page final book. These sketches and preliminary artworks reward close examination. Even details that the reader might not see on first glance are worked on with intense care. Look at the front endpapers of the book. You will need to take off the dust jacket to see the full timeline that Burton created. Each era and epoch is broken down to describe which animals emerged when, and many readers wouldn’t even notice.

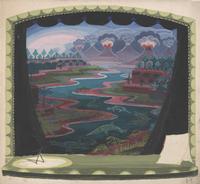

Although the drawings contain a wealth of detail, the collection contains very little personal information regarding Burton save a few notes about which hotels she stayed in when doing research at the American Museum of Natural History. Nor does the collection include any research she may have used or books that were consulted. The artwork itself tells the story. Burton tells the tale of life at its inception through an illustrated stage play. The acts and scenes are narrated by a cast of characters including an astronomer, a geologist, a paleontologist, a historian, a grandmother, and Burton herself. The final pages depict the last twenty-five years of her life in Folly Cove, where she lived until passing away on October 15, 1968 at the age of fifty-nine.

The book itself is a personal story, but I can’t say I know Burton after cataloguing her work. The artwork, of course, is rich and vibrant and the book is so wonderful that it makes me want to know more about Burton as a person. I am so taken in by her designs and text, it’s as if I were looking at her letters or her diary. It makes me wonder if an artist is more than their artwork, or do they need to be? Are biographical details irrelevant to appreciating an artist's work? Or does knowing more about their life enrich our understanding of their art?

-Lindsay Friedman

If you’d like more news from the Children’s Literature Research Collection, visit our Facebook page or follow us on Twitter.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.