Church bells ring incessantly throughout deserted streets. Homes are abandoned and those that are not are barricaded against strangers and friends alike. Formerly bustling markets stand empty except for a handful of vendors who put profit over safety. Outside City Hall, gravediggers with empty coffins await assignments while the few officials left in the city debate what to do next...

No, it’s not the Zombie Apocalypse. It’s the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793.

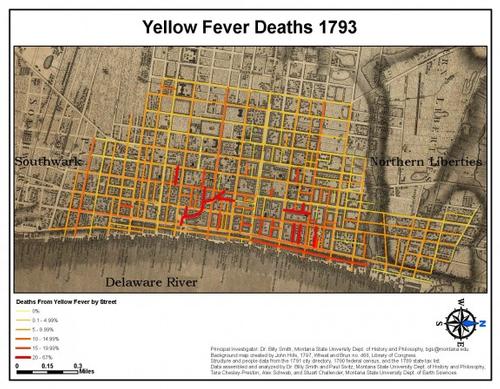

Philadelphia, the new nation’s capital, largest city and busiest port had become a ghost town. Almost everyone who could—about 40% of the population—travelled north to Germantown or west across the Schuylkill. They left behind the poor, who had nowhere to go, the physicians, desperately trying to save their patients, and the lawyers, busily drafting wills for the dying.

Delirious victims stumble into the streets, skin yellow, blood dripping from nose and gums, disgorging black vomit from internal hemorrhaging. Many are taken to Bush Hill, an empty mansion commandeered by the city to serve as a hospital for the poor. There they die in squalor and pain and are buried in trenches.

City, state, and federal governments left the city, but Mayor Matthew Clarkson and his committee of volunteers met day and night at City Hall on Chestnut Street. Clarkson asked French-born financier Stephen Girard for help. Girard, who had experienced similar epidemics in Santo Domingo, took charge of Bush Hill and used his fortune to clean it, staff it, and provide bedding and good food for the patients. He brought in Dr. Jean Deveze, a refugee from Santo Domingo, to run the hospital. Deveze followed the "French treatment" which emphasized clean air, good food, and wine to support the patient’s own healing capabilities. The College of Physicians supported this view and many members treated their patients accordingly.

Other physicians followed the prestigious Dr. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence, who prescribed copious bloodletting, purging, and large doses of mercury to rid the victims of "bad humours." These doctors were aided by hundreds of African-American volunteers, both slave and free. It was commonly believed that African-Americans were immune to Yellow Fever and community leaders, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, saw this as an opportunity for African-Americans to gain respect. They encouraged their followers to volunteer and hundreds did. Rush trained many of these volunteers to bleed and purge the sick. Others worked as nurses or buried the dead. In the end, the prevailing wisdom proved incorrect and over 200 African-Americans perished in the epidemic.

People left in the city try to protect themselves by smoking tobacco, chewing garlic, wearing bags of camphor, and washing in vinegar. There are no ships in the harbor, no farmers in the markets, no one in the locked and boarded stores. The starving scavenge gardens and trash bins for scraps.

By October the death rate had risen to 100 per day. George Washington was in a quandary. The U.S. government had been dispersed since mid-summer and had important work to do, but the Constitution stated that the government must meet in Philadelphia. Fortunately a severe frost in late October killed the mosquitoes that were spreading the virus and the death toll dropped precipitously. The government returned to Philadelphia. By the end of the epidemic, 5,000 Philadelphians—10% of the population—had lost their lives.

In the aftermath, city officials created the Philadelphia Board of Public Health to do whatever possible to prevent future outbreaks. This led to street cleaning, a city water system, and construction of The Lazaretto, a quarantine facility for cargo and passengers arriving from infected ports. More than 100 years passed before science determined that Yellow Fever was not contagious, but spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito (the same as Zika virus).

You can view the following episode from the documentary series Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, which further explores and visualizes the epidemic.

You can also read more about Yellow Fever from the following titles available in our catalog:

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.