This is the seventh in a series of posts highlighting major figures in Philadelphia jazz history. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library database.

In celebration of Black History Month, this post covers not one Philly Jazz Legend, but three. Moreover, it celebrates a Black family and their home at 19th and Federal Streets, where three children became world-class musicians who would appear on some of the most beloved classics of the mid-20th Century jazz canon.

Percy and Arlethia Heath moved to Philadelphia from Wilmington, NC, in 1923, bringing along their young daughter Elizabeth and their infant son Percy Jr. Jimmy was born in 1926 and Albert, the baby, in 1935. The family first moved to 57th and Ludlow Streets, but soon settled, like so many Black folks moving to Philly during the Great Migration, in Point Breeze. Percy Sr. worked as an auto mechanic and did a stint building bridges for the Works Progress Administration. He was also a clarinetist, playing with the all-Black Elks Quaker City Marching Band. Arlethia was a hairdresser and sang in the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church choir.

Both parents inspired an early love of music in their children. Albert recalled, "Ever since I can remember, my parents played the wonderful music of the 1930s and 1940s on a windup Victrola in the house, and I heard Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Dinah Washington, Marian Anderson, the Five Blind Boys. I had the best teachers in the world, from my mother and father to both my brothers." In his memoir, I Walked With Giants (from which most of this history is drawn), Jimmy recalls his mother taking him as a six year-old to see the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Pearl Theater at Ridge and Jefferson, where he would, as a school child, once bring a lunch to a Lionel Hampton matinee so he could catch all four sets.

The Heaths weren’t just raising listeners. Percy Jr. played violin in church and in a 2001 interview he describes singing and dancing in the Parisian Tailor’s Kiddie House, a children’s talent radio show that was broadcast live from the Royal Theater at 15th and South Streets. With the U.S.’s entrance into World War II, however, Percy was drafted into the military, leaving Jimmy to become the first professional musician in the family. As soon as Jimmy graduated high school (which he and Percy attended in North Carolina, staying with their grandparents), he joined Philadelphia trumpeter Calvin Todd’s big band, which played all over the Delaware Valley and even did some national touring. At the same time, he became obsessed with the modernist harmonic innovations of bebop—and in particular its leading trailblazer, Charlie Parker—inspiring him to start his own ensemble.

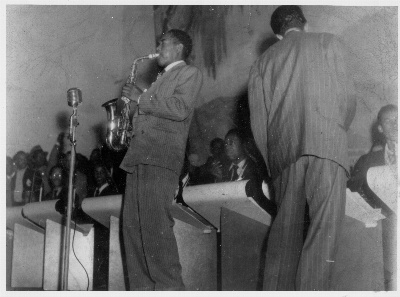

The Jimmy Heath Orchestra was formed shortly after Jimmy turned twenty, and debuted at Reynold’s Hall at Broad and Montgomery. They performed regularly in the Heath’s neighborhood at the O.V. Catto Lodge at 16th and Fitzwater Streets, as well as at a weekly Tuesday night gig at the Strand Theater on Germantown Avenue, just south of Broad and Erie. They rehearsed in the Heath family living room, and featured several rising jazz stars, most prominently John Coltrane (subject of the first Philly Jazz Legends post) as well as saxophonist and composer Benny Golson. Years later, Golson gushed, "Enough cannot be said about Mr. and Mrs. Heath... who continuously put up with all of us who used to come to their home in South Philadelphia, remove all of the furniture in the living and dining room, then begin our rehearsal. No matter what we did, how much noise we made, or how late we did it, they were always our champions."

In 1947, a six-year-old from the neighborhood had her legs amputated in a horrible trolley accident. The Jimmy Heath Orchestra played a benefit and got their hero Charlie Parker to come down from New York to join the bill. Jimmy was able to convince Parker (widely known as "Bird") to sit in with his band, and he later recalled that Coltrane "was watching Bird with his mouth open in amazement, concentrating so hard on what Bird was playing that he almost burned his hand because he forgot about his cigarette." In a 1960 interview, Coltrane remembered that Jimmy Heath and he had "musical appetites [that] were the same. We used to practice together... We would take things from records and digest them." In a 1987 Inquirer article, Jimmy said "I remember John and I used to go to the public library to listen to records by Stravinsky and Bartok after we saw Charlie Parker carrying the sheet music of Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite." The Jimmy Heath Orchestra disbanded in 1949, when these two keen students were hired by jazz superstar (and former Philadelphia resident) Dizzy Gillespie.

Gillespie’s trumpet, alongside Parker’s alto saxophone, had formed the defining front line at the birth of bebop, and his integration of the genre’s harmonic complexity into a big band setting was hugely influential to all of the Heath brothers. Just a year after bringing Jimmy into his world-touring ensemble, Gillespie launched Percy’s career as well. While in the military, Percy trained as one of the esteemed Tuskegee Airmen. "Then," as he put in an interview much later in life, "they dropped the atomic bomb and I wasn’t too proud of that, and mama was a nervous wreck, so I got out and bought a bass." He soon secured work as the house bassist at the Downbeat, the first racially integrated jazz club in Center City. After two years with Gillespie, he and fellow Gillespie alums founded the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1952, which would pioneer a brilliantly restrained chamber jazz sound over its celebrated forty-plus-year career.

By this point, Percy and Jimmy had both moved to New York City, but their baby brother Albert, known as "Tootie," kept the flame alive in Point Breeze. Ten and twelve years younger than his big brothers, Tootie had been known to play on a toy drum kit while Jimmy’s Orchestra was rehearsing in the living room. As a teenager, Tootie found work as a house drummer at the Blue Note at 15th and Ridge and the Showboat at Broad and Lombard Streets where he backed such giants as Thelonious Monk, Lester Young, Oscar Pettiford, and Stan Getz. He also formed a working trio with neighbors Ted Curson and Sam Reed—the former would go on to have a long career with Charles Mingus among others; the latter would accompany James Brown and The Supremes, and eventually become musical director for Philly’s own Teddy Pendergrass. By the mid-1950s, Tootie was touring in the band of organist and Philadelphian Shirley Scott, which also often included John Coltrane on sax. When Coltrane secured a contract for his solo debut, the 1957 classic Coltrane, he brought Tootie along as his drummer, and all three Heath Brothers were officially jazz royalty.

Now let’s get to what they recorded.

Beginning in the early 1950s under the direction of pianist John Lewis, the Modern Jazz Quartet released a bevy of quietly sizzling records, featuring Milt Jackson on vibraphone and of course Percy Heath on bass. Modern Jazz Quartet/Milt Jackson Quintet couples the first MJQ release from 1952 with a like-acronymed five-piece led by vibraphonist Jackson in 1954. Concorde (1955) and Django (1956) are MJQ classics, though less well known (to your humble librarian-blogger, at least) is the delectable Sonny Rollins with the Modern Jazz Quartet, a 1956 album that compiled some of the tenor giant’s recordings from earlier in the decade (this was common practice in the 1950s, with the advent of the new LP format). Check out the subtly fierce groove laid down on album opener "The Stopper" by Percy and the first MJQ drummer, Kenny Clarke.

Before we turn to Jimmy, it’s worth marvelling at the rhythm dynamo of Percy and Pittsburgh-native Clarke, who’d frequently been Gillespie and Parker’s drummer when bebop was being born in early 1940s late-night sessions in Harlem. In 1954 alone, the two of them backed Rollins on Moving Out, trumpeter Kenny Dorham on his debut, The Kenny Dorham Quintet (also featuring Jimmy Heath), and Miles Davis on four ten-inch records compiled in 1957 as two classic LPs, Bag’s Groove and Walkin’. On the former, check out the lurching funky treatment of Rollins’s composition “Airegin.”

Jimmy Heath started playing professionally before his older brother, but his career was put on pause when the heroin addiction that he shared with so many jazz musicians of this era led to him spending 1955 to early 1959 in federal prison on a narcotics charge. He made up for lost time upon getting home, releasing a string of great albums, family in tow, including his debut as a leader, The Thumper (1959), the big band record Really Big! (1960), Triple Threat (1962), Swamp Seed (1963), and On the Trail (1964). All feature Tootie on drums, and all but the first and last have Percy as well. check out "Bruh Slim" from Triple Threat for a characteristically serpentine but bouncy Jimmy Heath composition.

Jimmy was also an in-demand sideperson at the time. Freddie Hubbard’s Hub Cap (1961), is a blistering hard-bop classic that also features drummer Philly Joe Jones (subject of the third Philly Jazz Legends post). That’s Right! (1960) finds Jimmy backing another second son, trumpeter Nat Adderley, younger brother of the great Julian "Cannonball" Adderley. Julian Priester’s Keep Swingin' (1960) pairs his tenor with the trombone of Priester, who holds the distinction of being the only person who ever played with both Sun Ra and SunO))).

As mentioned above, Tootie Heath’s recorded debut was also John Coltrane’s first release as a leader, Coltrane (1957). Tootie's percussion drives a couple stellar piano trio albums: Mal Waldron Trio (1959) and In Person (1961) by Philadelphian Bobby Timmons. He appears on an intriguing concept album by Philadelphian Benny Golson called Take a Number From 1 to 10 (1961), which starts with Golson’s solo tenor and adds a new player per track culminating in a ten-piece ensemble. Tootie also joins Percy to form the rhythm section for one of the most beloved jazz guitar albums ever made, The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1960), which was selected in 2017 by the Library of Congress to be part of the National Recording Registry. Check out the brothers sizzling on "Four on Six" underneath Montgomery—who was himself the eldest of three musician brothers from Indianapolis!

In the 1970s, the brothers formed their own eponymous band. Your humble librarian-blogger’s favorite of their albums -- 1975’s Marching On, which opens with a gorgeous piece with Jimmy on flute and Tootie on mbira (African thumb-piano) -- isn’t on the Jazz Music Library, but a couple of later ones are: As We Were Saying (1997) and Jazz Family (1998). The Heath Brothers continued on as a group when Percy passed away in 2005, but met their demise with Jimmy’s death in January of 2020. At 85, Albert “Tootie” Heath carries on the family tradition, performing regularly (pre-pandemic) and teaching at the Stanford Jazz Workshop, among other places.

This blog post is meant to provide you, reader, with a digital stack of records to check out. It’s also meant to celebrate a Black family that, in an era of acute racism and segregation, gave the world three musical giants. So let’s end with some more praise for Percy Sr. and Arlethia Heath. In Jimmy’s memoir, Milt Jackson remembers that “one of the first times I went to their house for dinner, Jimmy’s father put Charlie Parker records on and told everybody that we had to be quiet til dinner. It was one of those moments you always remember. I thought of Jimmy’s father along with another era, Louis Armstrong or back in the day.” A listener in 2021 might be excused for thinking of the music of Parker and Armstrong as equally “back in the day,” but in the late ‘40s the innovations of bebop were received with hostility by most of the older generation. Armstrong himself opined in a 1948 Downbeat interview that the beboppers “want to carve everyone else because they’re full of malice. . . any old way will do as long as it’s different from the way you played it before.” In the context of this sort of generational rejection, it must have been a life-changing blessing to have parents who welcomed the artistic innovations that their kids were bringing into the house, whether in the form of a bebop record to put on the stereo or a band to clear the furniture for.

The eldest Heath child, Elizabeth, somehow never became a musician, but her daughter became a poet. She wrote a tribute to the house at 19th and Tasker, composed after it was sold in 1972 (as printed in a 1991 Inquirer article):

"Through my threshold have passed all kinds

Some had great burdens on their minds

I offered them solace, allowed them release

and to many of them I've given peace.

I inspired their music, encouraged their goals

and I'm certain I salvaged a few stray souls."

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.

![[from left] Jimmy Heath (1926-2020), Percy Heath (1923-2005), and Albert](https://libwww.freelibrary.org/images/blog/FLPBlog/resized/heath-brothers-4-22-17.jpg)