ALs to Lady Blessington

Charles DickensItem Info

Physical Description: [4] pages

Material: paper

Transcription:

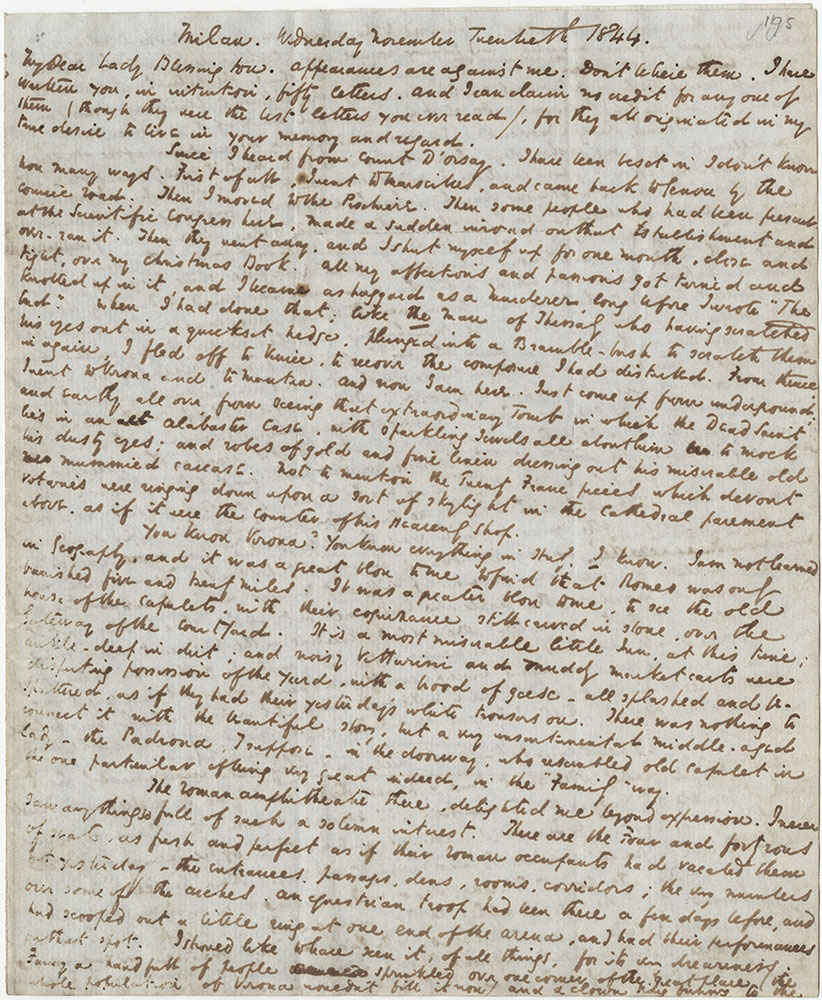

Milan. Wednesday November Twentieth 1844.

My Dear Lady Blessington. Appearances are against me. Don’t believe them. I have written you, in intention, fifty letters. And I can claim no credit for any one of them (though they were the best letters you ever read), for they all originated in my true desire to live in your memory and regard.

Since I heard from Count D’Orsay, I have been beset in I don’t know how many ways. First of all, I went to Marseilles, and came back to Genoa by the Cornice Road. Then I moved to the Peschiere. Then some people who had been present at the Scientific Congress here, made a sudden inroad on that Establishment, and over-ran it. Then they went away, and I shut myself up for one month, close and tight, over my Christmas book. All my affections and passions got twined and knotted up in it, and I became as haggard as a Murderer, long before I wrote “The End.” When I had done that; like the Man of Thessaly who having scratched his eyes out in a quickset hedge, plunged into a Bramble-bush to scratch them in again, I fled to Venice, to recover the composure I had disturbed. From thence, I went to Verona and to Mantua. And now I am here. Just come up from underground; and earthy all over, from seeing that extraordinary Tomb in which the Dead Saint lies in an Alabaster Case, with sparkling Jewels all about him to mock his dusty eyes: and robes of gold and fine linen dressing out his miserable old mummied carcase. Not to mention the Twenty Franc pieces which devout votaries were ringing down upon a sort of skylight in the Cathedral pavement above, as if it were the Counter of his Heavenly Shop.

You know Verona? You know everything in Italy, I know. I am not learned in Geography, and it was a great blow to me to find that Romeo was only banished five and twenty miles. It was a greater blow to me, to see the old house of the Capulets, with their cognizance still carved in stone, over the Gateway of the Court Yard. It is a most miserable little Inn, at this time; ankle-deep in dirt; and noisy Vetturini and muddy market carts were disputing possession of the Yard, with a brood of geese – all splashed and bespattered, as if they had their yesterday’s white trousers on. There was nothing to connect it with the beautiful story, but a very unsentimental middle-aged lady – the Padrona, I suppose – in the doorway, who resembled old Capulet in the one particular of being very great indeed, in the “Family” way.

The Roman amphitheatre there, delighted me beyond expression. I never saw anything so full of such a solemn interest. There are the Four and forty rows of seats, as fresh and perfect as if their Roman occupants had vacated them but yesterday - the entrances, passages, dens, rooms, corridors; the very numbers over some of the arches. An equestrian troop had been there a few days before, and had scooped out a little ring at one end of the arena, and had their performances on that spot. I should like to have seen it, of all things, for its very dreariness. Fancy a handfull of people sprinkled over one corner of the great place (the whole population of Verona wouldn’t fill it now) and a clown being funny to the echoes, and the grass-grown walls! I climbed to the topmost seat, and looked away at the beautiful view for some minutes; and turning round, and looking down into the Theatre again, it had exactly the appearance of an immense straw hat, to which the helmet in the Castle of Otranto was a Baby: the rows of seats representing the different plaits of straw: and the arena, the inside of the crown. Do shut your eyes and think of it, a moment.

I came through Modena (I am reminded of it by the mention of the strollers) on a brilliant day. One of those days when the sky is so blue that it hardly seems blue at all, but some other colour. – Lord Castlereagh might have said it, but it’s true. I passed from all this glory into a dark mysterious church, where high mass was performing, feeble tapers were burning, and people were kneeling about in all directions, and before all manner of shrines. Thinking how strange it was to find in every stagnant town, this same heart beating with the same monotonous pulsations; the centre of the same languid, torpid, listless circulation; I came out again by another door, and was scared to Death by the blast of the shrillest trumpet that ever was blown. Forwith, there came tearing round the corner, an equestrian company from Paris, marshalling themselves under the very walls of the church: flouting with their horses’ heels, the very Griffins and Tigers supporting its pillars. First of all, there came an Austrian Prince without a hat: bearing an enormous banner on which was inscribed “Mazeppa. Oggi Sera!” Then a Mexican chief, with a great club upon his shoulder, like Hercules. Then six or eight Roman Chariots: each with a beautiful lady in extremely short petticoats, and unnaturally pink silks, erect within: shedding beaming looks upon the crowd, in which there was an unaccountable expression of discomposure and anxiety, until the open back of each chariot presented itself, and one saw the immense difficulty with which the Pink Legs maintained their perpendicular over the uneven stones of the town – which was the drollest thing I ever beheld, and gave me quite a new idea of the ancient Romans and ancient Britons. The procession was brought to a close by some dozen warriors of different Nations, riding two and two; and when it passed on, the people who had come out of the church to look at it, went in again to that spectacle. One old lady kneeling on the pavement near the door, had seen it all, and had been immensely interested – without getting up. Catching my eye when it was all over, she crossed herself devoutly, and went down at full length on her face before a figure in a blue silk petticoat and a gilt crown; which was so like one of the other figures, that I thought her interest in the circus quite excusable and appropriate.

I had great expectations of Venice, but they fell immeasurably short of the wonderful reality. The short time I passed there, went by me in a dream. I hardly think it possible to exaggerate its beauties, its sources of interest, its uncommon novelty and freshness. A Thousand and One realizations of the Thousand and One Nights could scarcely captivate and enchant me more than Venice.

Pray tell Count D’Orsay, dear Lady Blessington, with my heartiest remembrances, that the receipt of his letter, was a long and deep notch in my then very wooden Calendar at Albaro. He did me but justice in supposing me able to read it without difficulty, as I have long been accustomed to read French almost as easily as English. But its sound is rather strange in my ears. I know it, as I know some men, perfectly by sight – and therefore I design, Please God, to spend next May and June in Paris, that I may enlarge my acquaintance with it, and encounter it upon easy terms. I have applied very little to the Italian: being lazy at first, and otherwise busy since. But I have great pleasure in what I know of it; and can understand, and be understood, without difficulty.

We like Italy more and more, every day. We are splendidly lodged – have a noble Sala – fifty feet high, and splendidly painted – and beautiful gardens. Mrs. Dickens and the children are as well as possible; our servants (contrary to all predictions) as contented and orderly as at home; and everything else “in a concatination accordingly”.

Your old house Il Paradiso, is spoken of as yours to this day. What a gallant place it is! I don’t know the present Inmate, but I hear that he bought and furnished it not long since, with great splendour, in the French style – and that he wishes to sell it. I wish I were rich, and could buy it. There is a third rate Wine Shop below Byron’s house; and the place looks dull and miserable and ruinous enough. Old De Negro is a trifle uglier than when I first arrived. He has periodical parties at the Villetta; at which there are a great many flowerpots and a few ices – no other refreshments. He goes about, constantly charged with extemporaneous poetry, and is always ready, like Tavern Dinners, on the shortest notice and the most reasonable terms. He keeps a Gigantic Harp in his bedroom, together with pen and paper for fixing his ideas as they flow – a kind of profane King David, but very harmless. Very.

I am in great hopes that I shall make you cry, bitterly, with my little Book; and that Miss Power and her sister will take it, also, to heart. I dare say you have forgotten that when we parted, I promised myself the pleasure of sending you an early proof to read, but I have not. So in the course of the first week of December, “about this time” – as Moore’s almanac says – “a packet may be looked for” – It will be a great pleasure to me to think that you have bestowed an hour upon it.

Pray say to Count D’Orsay, everything that is cordial and loving from me. His purse has been of immense service. It has been constantly opened. All Italy seems to yearn to put its hand in it. When I come back to England I shall have it hung up, on a nail, as a trophy. And I think of gashing the brim like the blade of an old sword, and saying to my son and heir, as they do upon the stage – “You see this notch boy? Five hundred francs were laid low on that day, for post horses. Where this gap is, a waiter charged me treble the correct amount – and got it. This end, worn into teeth like a file, is sacred to the Custom Houses, boy – the passports – and the shabby soldiers at town gates who put an open hand and a coat-cuff into the coach-windows of all Forestieri. Take it, boy. Thy father has nothing else to give.”

My desk is cooling itself in a Mail coach, somewhere down at the back of the Cathedral. And the pens and ink in this house (where the Great Mr. Lumley tarries, by the way) are so detestable, that I have no hope of your ever getting to this portion of my letter. But I have the less misery in this state of mind, from knowing that it has nothing in it to repay you for the trouble of perusal, and that you do not require its formal close to amuse you (or you would not have parted from me with such unaffected and genuine kindness) that I am ever, My Dear Lady Blessington, Faithfully and truly Yours, Charles Dickens.

P.S. I beg to be remembered to your Nieces. I saw a picture very like Miss Power, at Venice – and again denounced that Frankenstein of an artist, who had his Easel at Gore House when I left.

MssDate: Wednesday November Twentieth 1844

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Recipient: Blessington, Marguerite, Countess of, 1789-1849

Provenance: Gift of Mrs. D. Jacques Benoliel, 12/6/55.

Bibliography:

Volume 4, pp. 224-228, The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Madeline House & Graham Storey ; associate editors, W.J. Carlton … [et al.].

Country: Country:Italy

City/Town/Township:Milan

Call Number: DL B617m 1844-11-20

Creator Name: Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870 - Author

ALs to Lady Blessington

ALs to Lady Blessington

ALs to Lady Blessington

ALs to Lady Blessington  ALs to Lady Blessington

ALs to Lady Blessington  ALs to Lady Blessington

ALs to Lady Blessington