ALs to Frederick Dickens

Charles DickensItem Info

Physical Description: [4] pages

Material: paper

Transcription:

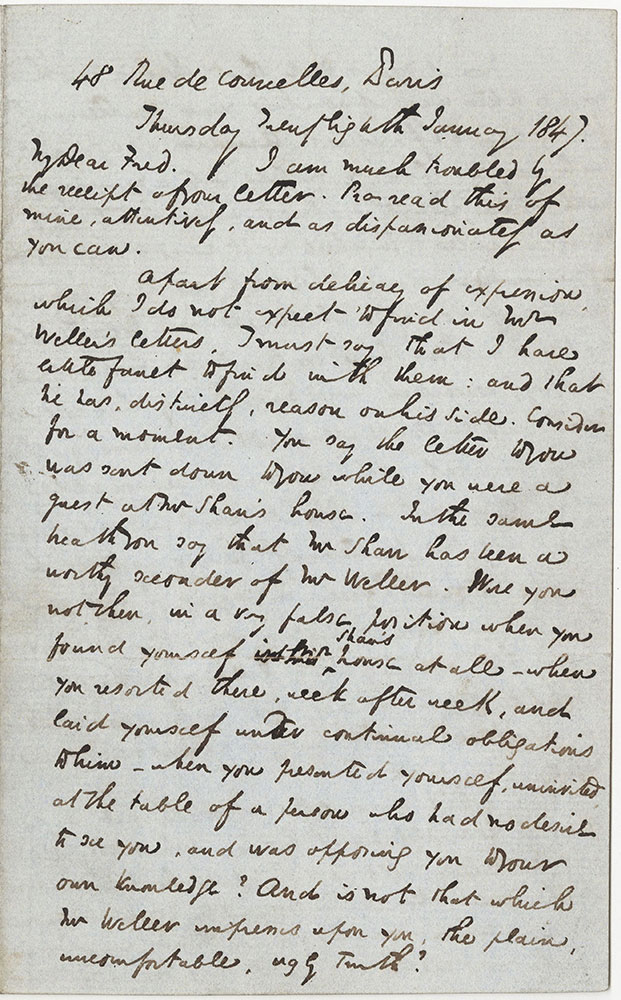

48 Rue De Courcelles, Paris

Thursday Twenty Eighth January 1847.

My Dear Fred. I am much troubled by the receipt of your letter. Pray read this of mine, attentively, and as dispassionately as you can.

Apart from delicacy of expression, which I do not expect to find in Mr. Weller’s letter, I must say that I have little fault to find with them: and that he has, distinctly, reason on his side. Consider for a moment. You say the letter to you was sent down to you while you were a guest at Mr. Shaw’s house. In the same breath you say that Mr. Shaw has been a worthy seconder of Mr. Weller. Were you not in a very false position when you found yourself in Mr. Shaw’s house at all—when you resorted there, week after week, and laid yourself under continual obligations to him—when you presented yourself, uninvited, at the table of a person who had no desire to see you, and was opposing you to your own knowledge? And is not that which Mr. Weller impresses upon you, the plain, uncomfortable, ugly Truth?

Now it seems to me that there is another and a better way of asserting your gentlemanly feeling and self-respect, as against such people, than by rushing into a marriage with self-respect is almost inconsistent and irreconcilable—for believe me it would be difficult among the daily and hourly recurring miseries of domestic shabbiness and poverty. Hold no terms with Mr. Shaw, contract no more obligations grudgingly conceded and bragged of by their cost in ponds and shillings afterwards—see Anna and by other means, and out his house, at reasonable intervals—wait—above all, wait—and there will more true and gentlemanly feeling and self-respect, two years hence, in saying I Did wait, than you can ever maintain against the just charge that you did not, though you were prepared to exhibit in your married life such an example of endurance and self-denial as were never seen before.

What “reasonable intervals” are, is a question we might easily settle. What they are not, Mr. Weller tells you. Again he has reason on his side. However disagreeable, it is common sense. When I was in London last, your own father and mother were quite as much alive to the want of common sense and reason in these weekly journies, as Mr. Weller is. —How much of the furniture of a small neat house, do you think they would pay for in two years, Fred?

When I believed you serious and resolved in regard to Anna Weller, I immediately withdrew all such family objections—so to call them—as I had pointed out to you, and felt that to urge them any longer would be indelicate and ungenerous. But the objection of her age, remains. Nothing but time can alter or remove it. In two years time, she will be very young to be married—unusually young, even then. But let it be then. I will do what I can for you, then, in the way of starting you in life; I will use my utmost influence with Mr. Weller to arrange all matters of dispute between you, happily. Or, on that understanding, I will even step in now—very much against my will—and endeavor to conclude some friendly and reasonable arrangement which shall recognize your claim to some kind of communication with Anna Weller which does not involve a weekly sojourn some hundred and twenty miles away, in the house of a man who does not desire to receive you; or her giving you the meeting at other houses where she herself goes on sufferance, and at your solicitation.

Your life is one of perfect misery, you say. I have no doubt of it, in this scrambling, unsettled, disjointed state of things. But it would be greatly changed, and immeasurably improved if you would look the prospect before you, steadily in the face—mark out some definite and sensible course of action for such a period as I have named—and abide by it. It is not very difficult to do. It is done by many people, every day—by men older than you, and women (still girls) far older than Anna—and for much longer terms.

And you must balance your present condition, and the improvement you might so effect in it—not against a honeymoon or a wedding-day, but against a drudging life, with butchers, bakers, landlords, tax-gatherers, doctors, and sickbeds, coming round in their turns as regularly as any star in the sky. If it came to a struggle after all, one of you certainly would bear it better two years hence—and both of you, I think.

You persuade yourself that you have considered all these things, deliberately. I know better. There is the strongest evidence to the contrary in every pothook in you letter, and the whole temper of your mind. Take time to consider, or take time until we can talk.

MssDate: Thursday Twenty Eighth January 1847

Media Type: Letters

Source: Rare Book Department

Notes:

Although Charles Dickens disapproved of Fred's relationship with Anna, Fred ignored his brother's advice and married Anna on 30 December 1848. In 1858 the couple applied for a judicial separation on the grounds of adultery. Anna was granted alimony, which Fred Dickens refused to pay, leaving the country. On his return in 1862 he was arrested and imprisoned for debt.

Thomas Weller, Anna's father, was concerned about Fred's prospects and Anna's age.

Recipient: Dickens, Frederick William, 1820-1868

Provenance: A Gift Mrs. D. Jacques Benoliel, 12/6/55.

Bibliography:

Volume 5, pp. 17-18, The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Madeline House & Graham Storey; associate editors, W.J. Carlton…[et al.]

Country: Creation Place Note:48 Rue de Courcelles

Country:France

City/Town/Township:Paris

Call Number: DL D556f 1847-01-28

Creator Name: Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870 - Author

ALs to Frederick Dickens

ALs to Frederick Dickens

ALs to Frederick Dickens

ALs to Frederick Dickens  ALs to Frederick Dickens

ALs to Frederick Dickens  ALs to Frederick Dickens

ALs to Frederick Dickens