A History Minute | The Fortunes of War - The Philadelphia Bankers Who Saved Our Nation

By Sally F.War runs on credit and the money it produces. Without money, weapons can’t be bought, ships can’t be built, soldiers can’t be fed, and the war is lost. In the first 100 years of our existence as a nation, the United States fought three wars that nearly destroyed our country. In each case we were saved by a Philadelphia banker.

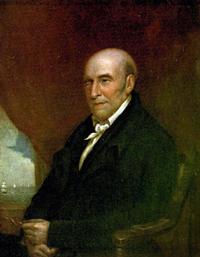

Robert Morris and the Revolution

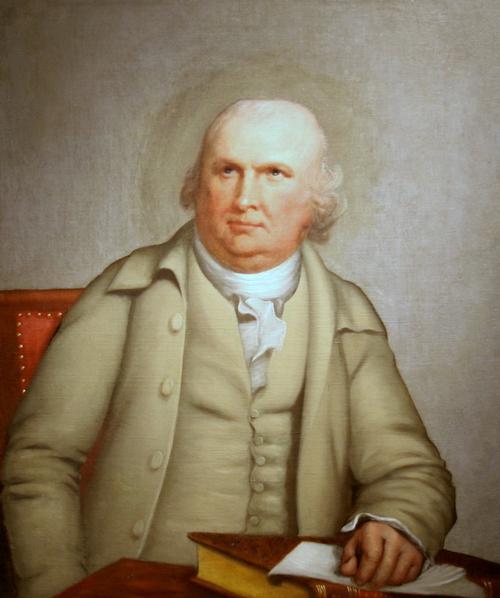

Morris was not in favor of war with Britain. War is bad for business, particularly when your most valuable assets are floating targets for the world’s greatest navy. And he did not think the colonists could win. But Morris was a patriot. As a member of the Continental Congress’ Secret Committee, he was charged with acquiring arms, munitions, and ships for the war he hoped could be avoided. The committee was secret because its activities were considered treason and punishable by death. Morris continued to argue for reconciliation with Britain but when the time came, he signed the Declaration of Independence, right next to John Hancock.

Throughout the Revolution, Morris used his ships, his trade network, and his fortune to supply Washington and his troops. When the Continental Congress had printed so much currency that it became worthless, Morris issued his own notes – promises to pay based on his own credit. These "Morris Notes", amounting to $1 million by war’s end, became currency in Philadelphia. He was able to secure substantial loans from French aristocrats as well. He used part of these funds, along with his own, to fund the Bank of North America, America’s first national bank, which put the war, and later the colonies, on more stable financial footing. It is estimated that Morris provided 75% of the total cost of the war from his own funds and credit.

After the war, Morris’s own finances did not fare well. Like many of the Founding Fathers, Morris believed immigrants would flock to our shores and he invested heavily in land. He lost everything when the market collapsed in America’s first real estate bubble. Morris was sent to debtor’s prison, the Prune Street jail, only two blocks from his residence. During his 3-1/2 year confinement, his old friends visited, including George Washington. Meanwhile his wife, Mary, managed his remaining businesses and tried to repay his debts. Morris was released in 1801, after Congress passed the first bankruptcy law. He continued to believe that his land would increase in value and his debts repaid. He died, still penniless, in 1804, and is buried in Christ Churchyard. He is immortilized in the Brumidi painting in the eye of the U.S. Capitol Building rotunda, which shows Mercury handing him a bag of money.

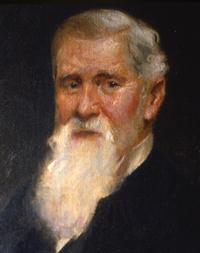

Stephen Girard and the War of 1812

Girard was not interested in the trappings of wealth. At age 62 he still lived in the house above his business on Water Street, just north of Market, where he worked seven days a week. He traveled in a gig, a small, two-wheeled buggy pulled by one horse, rather than the lavish coaches and four-in-hands other rich men used. People knew Girard was well off, but no one knew just how rich he was. At least, not until he bought a bank.

Girard, like many businessmen, believed a central bank was essential to a stable economy. When the Bank of the United States’ 20-year charter came up for renewal in 1811, Girard campaigned for its renewal. But the renewal was defeated (by only 1 vote in each chamber) and the bank paid its creditors, returned depositors’ funds, and closed its doors.

Girard now saw a new business opportunity. He bought the bank’s assets for $115,000. He took possession of the bank building and its contents on May 9, 1812, and nine days later the Girard Bank was open for business, backed by $1.2 million in cash from Girard’s personal funds. A month later the U.S. declared war on Great Britain.

Congress voted for the war by a large majority, but saw no need to raise taxes to fund it. Instead, it authorized the U.S. Treasury to borrow $16 million. Bonds with attractive terms were offered for sale to banks and the general public. To protect investors, the loan would not be implemented unless the entire amount was purchased by April 5, 1813. Sales did not go well and neither did the war. Many Americans did not believe the U.S. could win this war and were not willing to risk their money. By April 1, 1813, the U.S. Treasury was empty and only $6 million in bonds had been sold.

Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin appealed to the country’s richest men. Unfortunately, most of their wealth was in land and businesses rather than cash. John Jacob Astor and a group of his friends agreed to fund $2 million if Gallatin could find funders for the remaining half of the loan. He went to Stephen Girard. Girard could have insisted on favorable terms or government concessions for his business, but he did not. He simply subscribed to "the residue of said loan": $8,105,800. It was more than all of his holdings, but his credit was excellent, better than the credit of the United States. He would provide the funds and if the U.S. lost the war he would lose everything.

The entire $16 million went to the war effort, allowing the army and navy to go on the offensive and eventually win the war. Girard and all the others who bought bonds made a profit and the U.S. freed itself from Great Britain once and for all. Girard went on to become one of Philadelphia's great philanthropists.

Jay Cooke and the Civil War

The losses at Bull Run convinced the North it could not rely on state militias and would need a well-funded federal force to win the war. By the end of 1861, the War Department was spending $1.5 million a day, almost 10 times the entire government’s daily expenditures before the war. Once again, the government issued bonds to pay for a war. Secretary Chase asked Cook’s help in selling bonds to the New York money men and Cooke was so successful that Chase appointed him the sole agent for government bonds.

Cooke responded by devising bonds in small denominations so that ordinary citizens, not just banks, could afford them. He hired 2500 agents to travel the country selling bonds to banks and individuals and advertised the bonds in newspapers. Newspapers responded with stories and editorials linking bond purchase to patriotism. Cooke also supported the price of the securities in the money market, an innovative practice used today with municipal bonds. By 1864, Cooke was selling $2 million in bonds every day, enough to fund two thirds of the federal government’s expenditures during the war. His methods for selling bonds were used again to fund both WWI and WWII.

Cooke was an abolitionist and a patriot, but he was also a banker and his success with war bonds led to many opportunities after the war. He became partner in several banks and a major investor in railroads. Cooke also built a mansion in Elkins Park and named it "Ogontz" after a Native American chief he had known in Ohio. The mansion is gone but the name lives on as a neighborhood and an avenue.

Cooke’s sizeable investment in building the Northern Pacific Railway led to his bankruptcy in 1873, but he recovered his fortune by 1880 and paid off his debts. Jay Cooke died in 1905 and is buried in St. Paul's Episcopal Churchyard in Elkins Park.

Read more...

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.