Women today often talk about the difficulty of "having it all", but Sadie T.M. Alexander was more concerned with "doing it all." She not only raised two children and worked to advance her husband’s political aspirations, she also achieved major milestones as a student, an attorney, a city administrator, a civil rights leader, and a political figure. She may just be the perfect Philadelphian to highlight during Women's History Month!

Sadie Tanner Mossell was born in Philadelphia in 1898, the youngest of three children. She was only a year old when her father deserted his family and moved to Wales. Her mother, Mary Louise Tanner, suffered from depression and often relied on family to care for her children. Sadie split her time between her maternal grandparents in Philadelphia and her Uncle Lewis’s home in Washington, DC. It proved to be a nurturing and stimulating foundation for a remarkable life.

Sadie must have known from an early age what would be expected of her. She grew up surrounded by high-achieving, ground-breaking men and women. Her father, Aaron Albert Mossell was the first African-American to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Her maternal grandfather, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, was a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and founding editor of the first African American scholarly journal. Her aunt, Dr. Halle Tanner Johnson, founded the Tuskegee Institute’s Nurses’ School and Hospital. Her uncles were world-renown painter Henry Ossawa Tanner and Lewis Baxter Moore, dean of Howard University Teacher’s College. Every one of them faced down hatred and bigotry to achieve success. Sadie could do no less.

In 1915, Sadie entered the University of Pennsylvania, where she majored in Education. There were few women students at Penn and they ignored the young black woman among them. "You spoke perfect English but no one spoke to you," Sadie remembered. "Circumstances made a student either a dropout or a survivor so strong that she could not be overcome..." She overcame by graduating with honors in just three years. Though she qualified, Phi Beta Kappa did not admit her.

Sadie continued her studies at Penn and in June 1921, she became the first African American in the U.S. to earn a Ph.D. in economics.

She was also the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in the U.S. (She was followed in the same month by Georgiana Simpson of the University of Chicago and Eva Beatrice Dykes of Radcliffe, both in philology.) At this time, Sadie also served as the first national president of the black women’s sorority, Delta Sigma Theta. After graduation, Sadie had hoped to teach but the white colleges would not hire black teachers and the black colleges would not hire women teachers. She settled for a job as an actuary at a black-owned life insurance company in North Carolina.

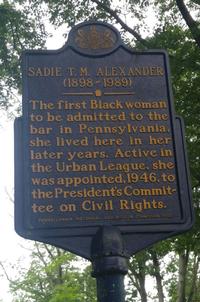

Two years later, Sadie was back in Philadelphia to marry her college sweetheart, Raymond Pace Alexander, a recent graduate of Harvard Law. After a frustrating year of keeping house, Sadie returned to Penn as the first African American woman to enroll in the School of Law. She soon became Associate Editor of the Law Review, the first African American woman to serve on its board. In1927, Sadie became the first African American woman to earn a law degree from Penn, the first to pass the Pennsylvania Bar, and the first to practice law in Pennsylvania. She immediately joined her husband’s law firm where she specialized in estate and family law, while also working with Raymond on civil rights issues. In 1928, Sadie became the first African American woman to serve as City Solicitor of Philadelphia, a post she held for two 4-year terms.

The Alexanders helped draft the 1935 Pennsylvania state Public Accommodations Law which prohibited discrimination in public places. In the beginning, the law was largely ignored. Once again, Sadie and Raymond took action. They tried to gain admission to several theaters, hotels, and restaurants, and each time they were turned away they had the manager arrested for breaking the new law. During this time, the Alexanders also found time to begin their family and Sadie gave birth to two daughters, Mary and Rae.

In 1943, Sadie became the first woman to serve on the board of the National Bar Association. She was the National Secretary of the National Urban League for 25 years. She also held national offices with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Americans for Democratic Action.

In 1946, President Truman appointed Sadie Alexander to his new Committee on Civil Rights. The committee’s report, "To Secure These Rights" became the foundation of the civil rights movement and the basis for future civil rights legislation. In 1951, Sadie co-founded the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, making Philadelphia the first city to have such an agency. She served on the commission for 16 years. In 1959, Raymond became a judge and closed his practice. Sadie opened her own law firm where she continued to practice law until 1982. In 1981, President Carter named her Chairwoman of the White House Conference on Aging.

Sadie Alexander died in 1989 at the age of 91. Her legacy is summed up in this advice she gave to young black women in a 1981 interview:

"Don't let anything stop you. There will be times when you'll be disappointed, but you can't stop. Make yourself the very best that you can make of what you are. The very best."

Additional Resources

Books:

Pathfinders: The Journeys of 16 Extraordinary Black Souls by Tonya Bolden

Podcast:

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.