A Science Minute: 7 Female Philadelphia Scientists You've Probably Never Heard Of

By Sally F.Science is the star this week around Philly, with the start of the annual Philadelphia Science Festival beginning this past weekend. We thought we would delve deep into our book stacks and search out some noteworthy yet unheralded contributors to the world of science that have a local connection to Philadelphia, and lo and behold they also just so happen to be wise and groundbreaking women!

In 1850, Margaretta Morris and astronomer Maria Mitchell became the first women members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science while in 1859, Morris became the second female member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Margaretta Morris was born in Germantown and lived there her entire life with her sister, Elizabeth. Although she had no formal training, Morris spent her entire life working as an entomologist studying several important agricultural pests. She was the first to publish descriptions of the life cycle of the Hession fly, which preyed on wheat and the seventeen-year locust, which killed fruit trees. The Hessian fly was such a problem that American wheat was banned in England and Europe. Knowledge of its life cycle was essential to controlling the pest. Morris studied insects both in the field and by raising them at home under bell jars. She corresponded with entomologists in the US and Europe, but her papers were read to the scientific societies by men as it was considered improper for a woman to speak before a male audience. She also wrote articles under a pseudonym for the American Agriculturist.

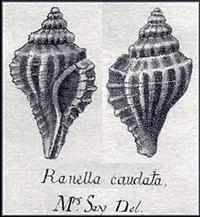

Lucy Say was the first woman to be elected a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, in 1841. Say was born in New London, Connecticut and educated in Philadelphia at the Fretageot School where she was taught drawing by Charles Alexandre Lesueur and also studied with James Audubon. In 1827, she married the naturalist Thomas Say and moved with him to the utopian colony of New Harmony, Indiana. Lucy Say created 66 drawings for her husband’s groundbreaking study of seashells as well as illustrating John Edwards Holbrook’s book about North American Reptiles.

Graceanna Lewis was an ornithologist, illustrator, teacher, abolitionist, and crusader for temperance and women’s suffrage. Lewis grew up on a farm in Chester County which was a stop on the Underground Railroad. When her mother died, Lewis continued her work, not just sheltering escaping slave families, but providing them with clothes and safe transportation. Lewis was educated at the Kimberton Boarding School for Girls and supported herself as a teacher of botany and chemistry at other girls’ schools. After Emancipation she pursued her studies in ornithology at the Academy of Natural Sciences with John Cassin, America’s leading ornithologist, who became her mentor. As a woman without a college degree, Lewis could not find work as a teacher or researcher. She supported herself as a scientific illustrator and by giving private lectures in ornithology in people’s homes. But she continued her research, which appeared in respected academic journals, and in 1868 she published Natural History of Birds, the first comprehensive book on American birds. Lewis’ botanical paintings were displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and the Chicago.

Rebecca Cole was the second African American woman in the U.S. to receive an M.D. degree and the first black graduate of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, in 1867. Cole was born in Philadelphia in 1846 and graduated from the Institute for Colored Youth in 1863. Cole was appointed resident physician at the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, where one of her responsibilities was to call on families in slum neighborhoods and educate them on prenatal and infant care and hygiene. After additional work in South Carolina and Washington, D.C., Cole returned to Philadelphia as superintendent of a shelter for the homeless. In 1873, she founded the Women’s Directory Center, which offered free medical and legal services to poor women. She later ran homes for homeless women and children in both Washington, D.C and Philadelphia. Cole died in Philadelphia in 1922, having practiced medicine for over 50 years. Cole is buried in Eden Cemetary.

In 1887, in an article in American Naturalist, Helen Abbott proposed her revolutionary thesis that plant chemical diversity is a product of evolution, and presented the first model of plant chemical evolution. 70 years later, this idea was validated and appropriated by several male chemists, transforming the field of plant biology. Helen Abbott was born in Philadelphia and trained as a pianist but left this career to pursue her interest in science. She studied at the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, writing her ground-breaking article after only four years of study. Abbott moved to Tufts University to study with Professor Arthur Michael whom she married in 1888. Abbott continued her study of chemistry for 10 years, publishing articles and lecturing throughout Europe before returning to medicine and earning her M.D. at Tufts in 1903. She established a hospital for the poor but died within a year of influenza contracted from a patient. Helen Abbott Michael is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery.

Helen Dean King was largely responsible for creating the Wistar Rat, the subject of research in biology, heredity, and medicine for the last 100 years. We take the lab rat for granted, but it was a revolutionary idea when King and her colleagues at the Wistar Institute set out to develop a strain of genetically homogeneous rats for research. King was born in Oswego, NY and graduated from Vassar College before becoming a graduate student in biology at Bryn Mawr College, where she received her Ph.D in 1899. She did postdoctoral work at Bryn Mawr and the University of Pennsylvania while teaching science at the Baldwin School. King joined the research staff of the Wistar Institute in 1908 and worked there until her retirement in 1950. In 1910, King became the first woman in America to hold a full professorship in research, and the only one until 1920. While developing the Wistar Rat, King continued her studies in genetics and embryology and was one of the first to show the effects of the environment on the sex ratio of species.

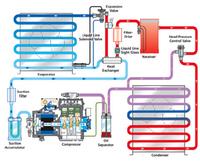

In the early 20th century, refrigeration was in its infancy and foods such as poultry, eggs, milk, and fish had to be bought shortly before being consumed. There were no standards for safe processing or transport of these perishables and many people died from eating contaminated food. Mary Engle Pennington developed the systems and safety standards for the refrigerated and frozen food distribution that we all benefit from today. She was born in Nashville, Tennessee but her family moved to Philadelphia shortly thereafter. In 1990, after graduating from a girls boarding school that offered no science courses, Pennington talked her way into UPenn’s Towne Scientific School and completed all requirements for a Bachelor’s Degree in 2 years. Since the school did not award degrees to women she was given a certificate of proficiency. She went on to earn a PhD in chemistry from Penn in 1895. Unable to find a job, Pennington formed the Philadelphia Clinical Laboratory, where she did bacterial analyses for medical doctors. She then became director of the bacteriological laboratory of the Philadelphia Department of Health where she developed techniques and standards for milk inspection and preservation that became standard throughout the country. In 1906 Harvey Wiley, head of the FDA, asked Pennington to head the Bureau of Chemistry’s Food Research Lab. After achieving the top score on her required civil service exam (taken under the name M.E. Pennington to disguise her gender) she set up the Food Research Lab in Philadelphia and began to develop the standards needed to implement the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. Over the next 40 years, as a civil servant and later a consultant, Pennington did meticulous research and traveled throughout the country (sometimes 50,000 miles a year) inspecting farms, food processors, and transporters and working with the industry to bring safe and high quality food to our tables. In 1920, Pennington became the first female member of the American Society of Refrigerating Engineers and she was awarded the American Chemical Society’s Francis P. Garvan Medal in 1940. Pennington died in 1952 and is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetary.

Use search terms like "science", "entomology", "ornithology", "plant evolution", and "medical research" throughout our online catalog and databases to learn more about those topics, or browse our Explore Topics that detail STEM and Genealogy resources.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.