This is the fourth in a series of blog posts highlighting major figures in jazz history who were in some sense from Philly. Every one of the bolded album titles below can be streamed for free with your library card via Alexander Street’s Jazz Music Library.

The first three subjects in this series (John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, and Philly Joe Jones) spent varying stretches of their youths in Philadelphia, before making their careers in New York City. This post covers someone who did the opposite: moving himself and his entire band to Philadelphia for the last couple decades of his long and winding career.

Herman Poole Blount was born in 1914 in Birmingham, Alabama. He was a musical prodigy and a voracious reader, as well as an eccentric thinker who was briefly jailed for refusing to serve in World War II. By the 1940s, he’d made his way to Chicago, where he played piano in the club scene, coached and arranged for vocal groups, and worked for a period as pianist and arranger for the legendary swing band leader Fletcher Henderson. By the early 1950s, he was leading groups that would evolve into his ensemble: Sun Ra and his Arkestra, aka Solar Arkestra, aka Outer Space Arkestra, aka Astro-Infinity Arkestra, aka Myth Science Arkestra, and a few more variations besides.

Sun Ra’s art is inseparable from the identity suggested by these many band names. In 1952, Blount legally changed his name to Le Sony’r Ra, soon simplified to Sun Ra. This rejection of what he and many others called "slave names" resembled that of Malcolm Little, who adopted the name Malcolm X just two years prior. But unlike those who sought a new identity in earthly cultures such as Islam, Sun Ra looked towards the cosmos.

There’s isn’t room here to unpack Sun Ra’s philosophy, which brought together African mythology, science fiction, and many strains of the occult, into a unique blend often called Afrofuturism. Anyone looking to plumb those depths should check out the lectures and reading list from the course on "The Black Man and the Cosmos" that Sun Ra taught at UC Berkley in 1971. A revealing glimpse of his thoughts can be seen in the lyric, "If we came from nowhere here / Why can't we go somewhere there?" Black people in the United States were (and still are) treated as strangers, unwelcome in the country they built. Perhaps a way to escape this racist trap is to seek cosmic citizenship.

What, then, would the cosmic citizen’s national anthem sound like? Having assembled his Arkestra, Sun Ra went about creating a style that fused a big band sound with avant-garde harmonies and an exploration of the outer limits of sound. The steadfast experimentalism of the Arkestra and the mystifying style of its leader didn’t lend itself to recording contracts, so Sun Ra started one of the first ever artist-owned labels, Saturn Records, named for the planet on which he maintained he’d been born.

The Arkestra was from Chicago, it’s leader was from Birmingham, and it’s essence was from Saturn, but the group didn’t attain widespread acclaim until they moved to New York City in 1961. There the Arkestra’s musical experiments dovetailed with the exploding "free jazz" and "New Thing" scenes around John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, and many others. Sun Ra’s mystical vision and his ensemble’s increasingly elaborate performances also fit in nicely with the psychedelic counterculture that was flowering out of the soil laid by the jazz-loving beatniks. (Though it’s worth noting that Sun Ra himself abstained from drink or drugs.) A typical concert included spectacular costumes, dancers, the band spreading out into the audience, and sometimes jugglers, fire-spinners, and the band launching flying saucer toys into the room.

But by 1968, the Arkestra’s East Village homebase was being sold, inspiring Sun Ra to relocate the band to Philadelphia, specifically to a row house on Morton Street in Germantown, owned by the father of alto saxophonist Marshal Allen. Asked about the move in 1990 by the Philadelphia Inquirer, Sun Ra’s answer was characteristically elliptical:

"To save the planet, I had to go to the worst spot on earth, and that was Philadelphia, which was death's headquarters"

—a line that local jazz presenters Ars Nova Workshop has printed on t-shirts and tote bags.

By this point, the Arkestra was doing larger and more lucrative concerts and tours, requiring more orderly finances than that of a trickster shaman. As a result, Danny Ray Thompson, who had been playing baritone saxophone and flute since the NYC days, took over managing the business side of things. Thompson also supplemented the group’s income by opening a shop in Germantown called the Pharaoh’s Den, which sold commonplace grocery store items while also spreading Afrofuturist art and thought in the neighborhood.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, it was not uncommon for Philadelphians to spot the extravagantly dressed Sun Ra around town. He was a regular at the Egyptian Hall at the Penn Museum, the site of a significant chunk of the 1980 film Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise. He loved the Mummers Parade, telling the Inquirer in that same 1990 interview, that he’d attended many times but that he couldn’t participate since "I have to keep a low profile because what I’m doing is so earth-shattering." Shortly before his death, he was hospitalized and a nurse, following procedure to assess cognitive status, asked him standardized questions: How many fingers do you see? What year is it? Where were you born? His answer to that last question caused alarm until a hip neurologist entered the room and said, "Oh, that’s Sun Ra. He is from Saturn."

All great musicians live on in their recordings, but since Sun Ra’s death (or return to Saturn) in 1993, the Arkestra has continued performing his music world-wide, first under the direction of tenor saxophonist John Gilmore until his passing 1995, then of alto saxophonist Marshall Allen. As of this writing, Allen is an astonishing 96 years old and still leads rehearsals, still conducts the band live, and can still peel paint with his alto and turn sound inside out with his EVI (Electronic Valve Instrument). Most current Arkestra members have joined in the 27 years since Sun Ra left us, but they still excel at summoning his unique blend of deep jazz tradition with otherworldly sounds.

That was a brief run-down of one of the most fascinating lives of the 20th Century. Those who want to know more are recommended to check out Space is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra by Philadelphia’s own John Szwed.

Now here’s that story told again, but in discographical form...

Spaceship Lullaby (recorded 1954-1960, released 2003) is a collection of rehearsal tapes of vocal groups that Sun Ra led before and in the earliest days of the Arkestra. While this is far from essential listening, it’s intriguing to hear melodic and lyrical fragments that would be incorporated into his later compositions. Don’t miss "Chicago USA," his submission to a contest for a new official Chicago theme song. It didn’t win.

Supersonic Jazz (1957) was the first release on Saturn Records, the independent label run by Sun Ra with his business associate Alton Abraham. As with all early Arkestra recordings, the band is clearly indebted to popular genre music, though always with a twist: eerie percussion colors the exotica of "India"; an angular melody jerks around the noir swing of "El is a Sound of Joy"; "Blues at Midnight" is a twelve-bar blues, but one that opens with a tympani fanfare and finds tenorist Gilmore breaking more than a few rules of blues harmony.

Jazz by Sun Ra (1957) was the first time Sun Ra had his music released on a label he didn’t run—thus the quotidian title. It’s similar to Supersonic Jazz in its off-kilter reimagining of big band jazz, but closes with kaleidoscopic "Sun Song," which presages some of the sonic experiments soon to come.

Interstellar Low Ways (recorded 1957-60, released 1966) pushes further into the stratosphere at a time when Sun Ra started dressing his musicians in the homemade "space costumes" that they still wear to this day. The album debuted two tunes that would become central to the Arkestra repertoire. On "Interplanetary Music", the band chants about "interplanetary melodies" and "interplanetary harmonies" while some sort of bowed zither saws out an unsettling counterpoint. "Rocket Number 9" could be compared to Dizzy Gillespie’s bebop hit "Salt Peanuts" but for its spacious and dissonant solos. It also marries galactic themes with the daily grind of city living by imagining the eponymous rocket as public transit ("Second stop is Jupiter!").

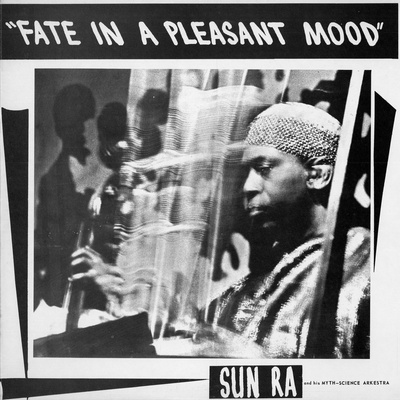

Fate in a Pleasant Mood (recorded 1960, released 1965) is the last album before the Arkestra’s move to NYC. Marshall Allen had just begun his sixty-year (and counting!) membership in the band and we can hear glimmerings of the alto pyrotechnics that would become his trademark on "Ahnknation." The album also features one of your humble librarian-blogger favorite compositions ever, "Lights on a Satellite."

On When Sun Comes Out (1963), the first Saturn Records release recorded in New York, we get the Arkestra’s bold contribution to their new avant-garde milieu. Horns squeal, multiple drummers generate rhythms that go off in different directions, and the composed harmonies are denser than ever before. Sun Ra’s version of 1960s experimentalism is still uniquely his own, particularly in its use of vocals, such as the echoing invocation of the title of "Calling Planet Earth" and the woozy soulfulness of "We Travel the Spaceways."

Other Planes of There (1964) opens with a thick dissonance that fades into a blistering Marshall Allen solo and proceeds farther through the spaceways than the Arkestra had yet traveled. Notably, the album resembles but precedes both the blow-out "energy music" of John Coltrane’s Ascension and the wide-open patience of the first recordings by Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (co-founded by Arkestra alum Kelan Phil Cohran).

By this point, Sun Ra’s acclaim was growing in the New York art world, leading the avant-garde label ESP-Disk to put out The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra (1965). The band is farther than ever from any earthly genre, and Sun Ra plays very little acoustic piano, instead focussing on bass marimba and newly available synthesizers.

The Magic City (1966) is probably as far out as the Arkestra ever went on a recording, particularly on the title track, which refers not to some metropolis on Venus but to the official nickname of Birmingham, AL. The piece sprawls over 26-minutes, on which Sun Ra conducts the Arkestra’s improvisation.

On Atlantis (1969), Sun Ra takes up the funky-toned clavinet—which he renamed the Solar Sound Instrument—for an album that’s more rhythmically and harmonically mellow than his experiments earlier in the decade... until the album-closing title track, an uncompromisingly furious representation of the flooding of the lost continent.

Space is the Place (1973) could be called a return to accessibility, albeit one where odd harmonies and howling horns are still the norm. The title track takes up the entire first side of the record, but unlike "The Magic City," it features a clear beat and a hummable hook. Sun Ra co-wrote and starred in a movie of the same name in which he winds up on a far-off planet (no surprise) and comes back to earth to open an "Outer Space Employment Agency" for Black youth in Oakland.

The Antique Blacks (1974), recorded for radio broadcast at Temple University, is an oddity in an already pretty odd discography. It features long sections of Sun Ra’s mystical sermonizing, usually over a variety of electric keyboards that at times resemble a church organ. The album also features your humble librarian-blogger’s favorite non-space-related Sun Ra song, "This Song is Dedicated to Nature's God."

On Some Blues But Not The Kind That's Blue (1977), the Arkestra continues its 1970s descent back to the realm of recognizable genre. The title track features dissonant solos, but over a cool blues shuffle. The band even makes its way through several standards, including "My Favorite Things"—written for The Sound of Music, but brought into the jazz orbit by John Coltrane—led by the tenor of John Gilmore, who Coltrane himself admired greatly.

Compared to the 1960s material, Lanquidity (1978) is practically a pop album, from the rock-ish stomp of "Where Pathways Meet" to the nearly hip-hop feel of "Twin Stars of Thence." The album closes with hallucinatory overdubs of voices whispering about "other worlds" that "wish to speak to you" layered over a minimal funky beat.

With Nuclear War (1982), Sun Ra brought his vision to the people with a hummable tune and an anti-nuclear message—though some have argued that the song’s wry lyrics and deadpan delivery could better be heard as a parody of political songwriting. The album also features crowd-pleasing standards, including Duke Ellington’s "Drop Me Off in Harlem" followed by the 1920s-era Broadway tune "Sometimes I’m Happy." These would seem to be anodyne selections... were it not for the fact that they start with an almost identical melody. Even arranging an accessible album, Sun Ra’s choices could be inscrutable.

Sun Ra’s profound eccentricity was no put-on, and even in the last chapter of his life, he was capable of head-scratching left turns. He one-upped the return of popular form in his music with 1989’s Second Star To The Right: Salute to Walt Disney, a live album that resulted from the septuagenarian’s newfound obsession with Disney music. If you ever wanted to hear a guitar and an oboe solo simultaneously over "Whistle While You Work," this is probably the only chance you’ve got.

Believe it or not, this list represents less than half of the Sun Ra albums you can stream through the Jazz Music Library, free with your library card!

This post is dedicated to the memory of Danny Ray Thompson (1947 - 2020) and to the vitality of Marshall Allen (1924 - ∞).

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.