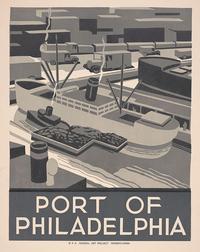

A History Minute | 14 Surprising Facts about the Port of Philadelphia

By Sally F.Philadelphia has been a major center of international commerce for over 300 years. Even today, with major port complexes serving major metropolitan centers throughout the country, Philadelphia and its international seaport maintains a preeminent position in several areas of trade.

Read on for 14 Surprising Facts (you may or may not know) about the Port of Philadelphia...

- When William Penn first landed on the west bank of the Delaware near Dock Creek, it was a bucolic spot.

The deep riverbank was lush with greenery and backed by a tall-forested embankment that would become the site of Philadelphia. The path that ran between the shore and the embankment became Water Street. Another path grew up along the top of the embankment and became Front Street.

- Penn knew that trade would be important to his city and he incorporated the Port of Philadelphia at the same time he incorporated the City.

Even before that, he helped James West set up a shipyard on the river, near what would become Vine Street, and he recruited trained shipbuilders from Bristol, England’s merchant center.

- By 1770, Philadelphia had become one of the British Empire’s most important ports.

Philadelphia merchants traded lumber and agricultural goods for sugar and rum from the Caribbean and tea from China.

- Winning the Revolution destroyed our overseas trade.

After the American victory, English ports in the West Indies were closed to American ships and the French Revolution reduced trade with France. The only bright spot was the possibility of direct trade with China. The first American ship to reach China was The Empress of China, financed by Philadelphia’s Robert Morris and investors from New York.

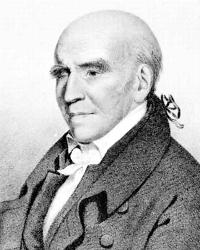

- Delaware Avenue was a gift from Stephen Girard.

Girard, like many merchants, lived and conducted his business in a mansion on Water Street. In the century following Penn’s arrival, the waterfront had grown outward into the river. The original landings had been replaced by docks, then by longer and deeper docks with warehouses on the inland side. These were accessed by a dirt road built on top of the original wharves. At his death in 1831, Girard left the city a bequest of $500,000 to construct Delaware Avenue along the waterfront. It was to be a tree-lined boulevard built on fill, paved with Belgian block, and lit with gaslights. Delaware Avenue became a busy thoroughfare and the main route for shipping and storing cargo, especially food, for the entire city.

Girard, like many merchants, lived and conducted his business in a mansion on Water Street. In the century following Penn’s arrival, the waterfront had grown outward into the river. The original landings had been replaced by docks, then by longer and deeper docks with warehouses on the inland side. These were accessed by a dirt road built on top of the original wharves. At his death in 1831, Girard left the city a bequest of $500,000 to construct Delaware Avenue along the waterfront. It was to be a tree-lined boulevard built on fill, paved with Belgian block, and lit with gaslights. Delaware Avenue became a busy thoroughfare and the main route for shipping and storing cargo, especially food, for the entire city.

- The waterfront was not reserved just for cargo.

Numerous ferries transported thousands of people daily to and from New Jersey. Pleasure boats sailed the river. In the winter, the frozen river attracted hordes of ice skaters and the ice was so thick that horses pulled the ferryboats across it. This ended in 1837 when the city commissioned the world’s first steam-powered icebreaker to keep the river open year round. The ferryboats disappeared in 1926 with the opening of the Delaware River Bridge (now the Ben Franklin Bridge).

Numerous ferries transported thousands of people daily to and from New Jersey. Pleasure boats sailed the river. In the winter, the frozen river attracted hordes of ice skaters and the ice was so thick that horses pulled the ferryboats across it. This ended in 1837 when the city commissioned the world’s first steam-powered icebreaker to keep the river open year round. The ferryboats disappeared in 1926 with the opening of the Delaware River Bridge (now the Ben Franklin Bridge).

- In the 1870s, passengers became as important as cargo.

Steam-powered iron ships were beginning to replace wooden sailing vessels throughout the world. This happened most quickly with passenger ships where the reduced time and cost of the trip enabled thousands more immigrants to reach America. Many of them found jobs in Philadelphia’s huge manufacturing centers building steam engines for industry as well as trains and ships. The Port of Philadelphia expanded in both directions from Penn’s original landing point. By 1899, the river channel had been deepened to 30 feet to accommodate the increasing size of ships. Philadelphia area factories produced ships and locomotives, men’s and women’s clothing, machine and hand tools, lighting fixtures and soup. They imported materials and exported finished goods, all of it made possible by the port.

- The Schuylkill River is an essential part of the port.

From the beginning, it was a main thoroughfare for moving goods from inland to the riverside. At first, this was largely lumber and agricultural goods, then coal and crude oil, which was refined in plants along the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers on the southern border of the city. By 1891, 35% of US petroleum exports were refined there.

- The Delaware River Port Authority does not manage the Port of Philadelphia or other ports on the Delaware River.

It was created in 1919 as the Delaware River Bridge Joint Commission to build and manage the Delaware River Bridge. The commission was renamed in 1951 and currently manages the Ben Franklin, Walt Whitman, Betsy Ross, and Commodore Barry bridges, as well as the PATCO speed line. It uses the tolls and fares to fund maintenance of the infrastructure and support economic development on both sides of the River. The Philadelphia Regional Port Association, a state agency, manages the Port of Philadelphia.

- The Belt Line Railroad has never owned a train.

The Philadelphia Belt Line Company was created in 1892 to build and operate 18 miles of track in the center of Delaware Avenue, giving all railroad companies access to the Philadelphia docks and breaking up the Pennsylvania Railroad’s monopoly. As manufacturing and exports declined throughout the second half of the 20th century, many connections to the tracks were removed. It still serves the docks south of South Street and is operated by ConnRail. The northern section of tracks was used for a tourist trolley in the 1990s and has been proposed as the beginning of a future light rail system for the city.

- It was a perfect storm of circumstances that nearly killed the port.

As manufacturing shifted to Asia, our plants began to close and exports dried up. As the U.S. shifted from exporting to importing, oil our refineries shut down. Meanwhile, regular cargo ships were being replaced by container ships, first used in the late 1950s. As the container ships grew bigger, they could no longer navigate the Delaware River, nor could they pass through the Panama Canal. This meant that cargo from Asia had to be unloaded on the west coast and trucked to the rest of the country.

- The Delaware River will soon be 28 feet deeper than it was when William Penn arrived.

In 1992, Congress approved digging the main channel 45’ deep south of the Walt Whitman Bridge to allow the largest container ships passage to our port. (These ships are too tall to pass beneath the bridge.) The project should be completed sometime in the spring of 2019.

- The enlarged Panama Canal, which opened in 2016, is capable of handling the largest ships in the world.

Now there are once again east coast options for Asian shippers. The state has invested $300 million to upgrade our docking and storage facilities, including two huge cranes.

- It’s not all about containers.

The port has expanded its refrigerated storage facilities and currently handles over 100 million boxes of perishable fruit from South America annually, as well as meat, cocoa beans, coffee, and other food products from the Mediterranean and South Pacific. These products can be shipped in refrigerated trucks to two-thirds of the U.S. and Canada within 48 hours. Philadelphia is the main port of entry for Hyundai and Kia cars, and we have cornered the market on eucalyptus pulp. The Tioga Marine Terminal warehouses this until and it is trucked to western Pennsylvania to be made into tissues and toilet paper.

Explore the development of the Port of Philadelphia for yourself through photos, drawings, and maps in the Free Library’s Print and Picture Collection and Map Collection.

Have a question for Free Library staff? Please submit it to our Ask a Librarian page and receive a response within two business days.