Blog Articles

What did we read in 2024? From "Most 2024" to "Terrible Schools and Awesome Adventures," Parkway Central Children’s Department has all the extremely specific book… continue reading The Central Children's Department's Book Awards of 2024

By written by Administrator December 19, 2024

We are pleased to reintroduce NoveList Plus , a longtime favorite electronic resource among book lovers. NoveList Plus is a database designed to help readers (or listeners) find their next books… continue reading Find Your Next Great Book with NoveList Plus!

By written by Tyler S. December 18, 2024

A Kwanzaa Keepsake by Dr. Jessica B. Harris, author of High on the Hog , is an invitation to honor, connect, create, and cook. Besides the cooking, it may move you to gather family recipes to… continue reading A Kwanzaa Keepsake: Celebrating with New Traditions and Feasts

By written by Aurora S. December 17, 2024

December is National Learn a Foreign Language Month! To celebrate, Languages and Learning , the adult learning department of the Free Library, is highlighting some of the resources available with… continue reading Learn a Foreign Language With Our Electronic Resources

By written by Meredith M. December 11, 2024

There are over 50 Free Library locations in neighborhoods across Philly, and everyone has a favorite, along with fond memories of Author Events ; One Book, One Philadelphia ; special… continue reading Giving Back With the Free Library Foundation

By written by Free Library Foundation December 9, 2024 1

The Free Library Board of Trustees will be holding its second meeting of FY25 on Friday, December 13, 2024, from 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. The meeting will be held in person in Rooms… continue reading Free Library Board of Trustees Public Meeting on Friday, December 13 at 8:00 a.m.

By written by Administrator December 6, 2024

Greetings from the Trans by Trans Book Club folks! Are you looking for recommendations based on our recent reads? Check out these book club read-a-likes. *Note - Not all titles are written by… continue reading Discover Queer-Friendly Reads Recommended by the Trans by Trans Book Club

By written by Flan P. December 6, 2024

December is National Learn a Foreign Language Month! Maybe you’re looking for something to do over your winter break or already thinking about your 2025 goals. There’s never a bad time… continue reading Celebrate National Learn a Foreign Language Month With Languages and Learning

By written by Meredith M. December 3, 2024

The Rare Book Department , located on the Third Floor of Parkway Central Library , is closed as of November 4th, 2024 for the installation of a new HVAC system. Climate control is of the… continue reading Temporary Closure of the Rare Book Department

By written by Allison F. December 2, 2024

It’s almost time to bundle up warm and join the Free Library for festive storytimes at the Christmas Village in LOVE Park! Every year, LOVE Park is transformed into an authentic German-style… continue reading Holiday Cheer for Children and Families

By written by Kayla H. December 2, 2024 1

There’s a lot to explore this December with a mix of new titles coming to the Free Library's shelves! Young Children (up to 2nd Grade) Wake Up, Moon! by Lita Judge A playful… continue reading New Titles Coming to the Free Library in December

By written by Rachel F. December 2, 2024 1

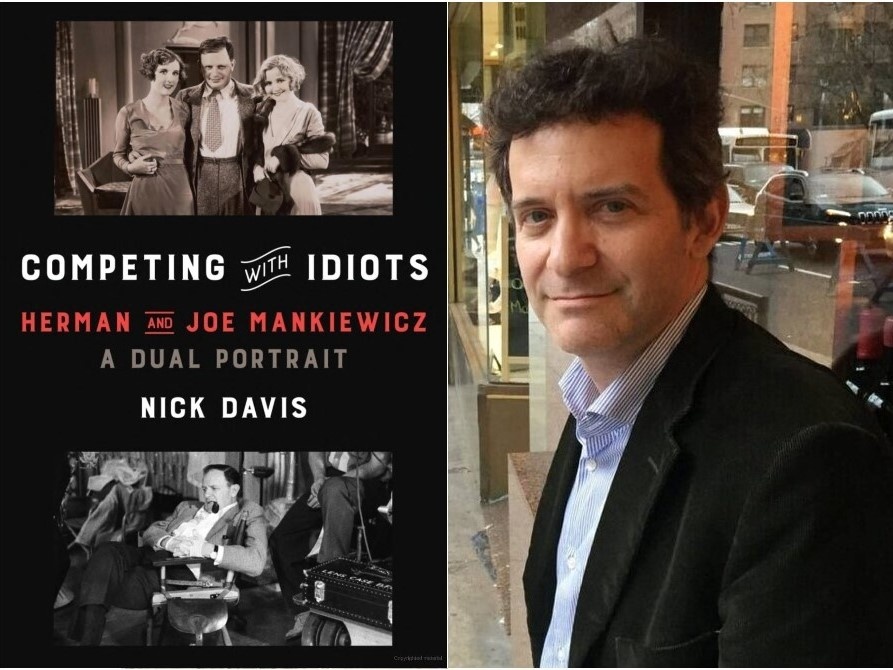

Few individuals better encapsulated the highs and lows of the Golden Age of Hollywood than the Mankiewicz brothers. Filmmakers Herman (1897–1953) and Joe (1909–1993) are the subjects… continue reading Learn About the Mankiewicz Brothers’ Impact on Hollywood With “Scripting the Movies”

By written by Anthony T. November 27, 2024 2

Fancy yourself as a do-it-yourself handyman or looking to pick up a new skill? Want to dive into the world of electronics and repair the wire in your mouse, or salvage your favorite… continue reading Learn the Art of Soldering at the Library

By written by Brianna V. November 26, 2024

Come celebrate Giving Tuesday at the Business Resource and Innovation Center (BRIC) in Parkway Central Library with this special event hosted by Michelle Snow on December 3, 2024.… continue reading Take Your Nonprofit to the Next Level This Giving Tuesday

By written by Jordan C. November 26, 2024

It's Thanksgiving week! In the spirit of the holiday, here are some local Thanksgiving-related community events, including turkey drives, giveaways, and free Thanksgiving meals for… continue reading Local Thanksgiving Meals and Giveaways for Those in Need

By written by Bridget G. November 25, 2024 4

November is National American Indian Heritage Month, also known as Native American Heritage Month . While different single-day observations began across the country early in the 20th century, it… continue reading Native American Heritage: Language Resources

By written by Meredith M. November 14, 2024 1

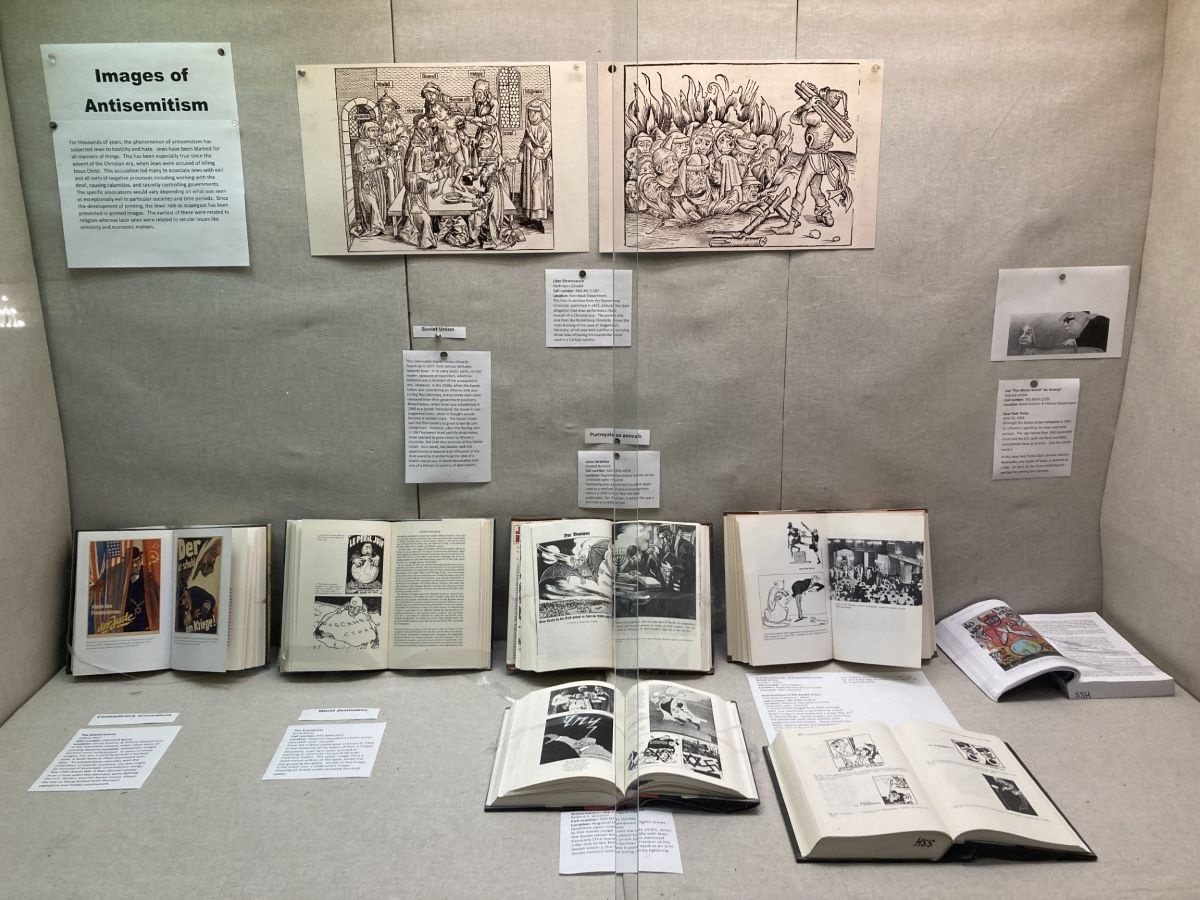

On December 16 at 6:00 p.m. at Parkway Central Library , the Social Science and History Department will host Bob Weinberg, Professor of History and International Relations at Swarthmore College.… continue reading The Dehumanization of Jews in Russian and Soviet Cartoons

By written by Hal T. November 13, 2024

The Free Library of Philadelphia Foundation supports the Free Library of Philadelphia as a center for learning and opportunity in every neighborhood, for every Philadelphian. With the holiday… continue reading What We Are Thankful for at the Free Library of Philadelphia Foundation

By written by Free Library Foundation November 12, 2024

Podcasting has exploded in popularity since 2006, when just 11% of Americans over 12 were familiar with the medium. Now, that number is over 67%, with 45 million people that enjoy podcasts at… continue reading Learn to Start Your Own Podcast with "Podcasting 101"

By written by Anthony T. November 8, 2024

Children’s Book Week, a “celebration of books for young people and the joy of reading,” was established in 1919 and is “the longest-running national literacy initiative in… continue reading Read by 4th and Children's Book Week: Ensuring Our Children Become Strong Readers

By written by Free Library Foundation November 1, 2024

![Cardinell, John D. - Photographer. (1926). Sesqui-Centennial Performance #37. [Silver Gelatins]. Retrieved from the Free Library of Philadelphia's Print and Picture Collection](https://libwww.freelibrary.org/images/blog/FLPBlog/orig/native-american-family.jpg)